by Tobias Kunz

As the changing seasons make outdoor activities increasingly unattractive, the slow re-opening of cinemas has coincided, unsurprisingly, with the return of superhero blockbusters to the top of the box-office rankings. Films like Black Widow, Shang-Chi and the Legend of the Ten Rings or Suicide Squad (all 2021) and the comics that inspired them have become cultural mainstays and are being taken seriously by casual viewers and academics alike.

However, these big-screen adaptations are in many ways less challenging and ambitious than the work that arguably made their success possible in the first place. Today, Watchmen, written by Alan Moore and illustrated by David Gibbons, is still being regarded as essential reading, featuring not only on lists of the best graphic novels, but also, perhaps most prominently, on Time Magazine’s 2005 list of the 100 best English Novels published since 1923. 35 years after the publication of its first issue, cover-dated September 1986, it is well worth taking a brief look at Watchmen’s unique qualities, and its considerable cultural legacy.

Subverting the Superhero

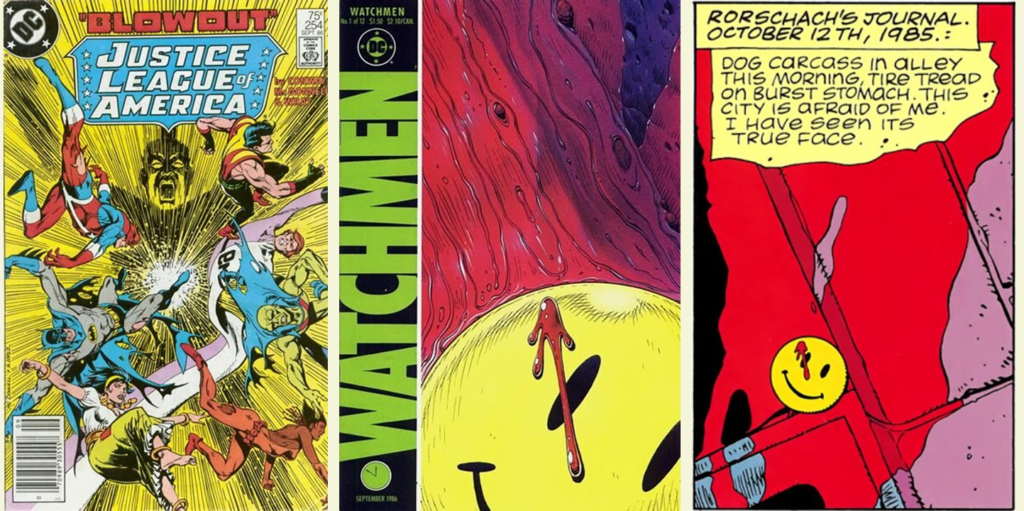

Like most comic books of its time, Watchmen was initially published in monthly “floppies”, magazines of roughly thirty full-colour pages. However, the cover of the first issue already suggests a stark difference from most concurrently running series in the medium: Rather than depicting a dynamic scene focused on characters and representing the overall plot, Watchmen’s twelve covers all show extreme close-ups of the respective instalment’s first or second panel.

From left to right: The covers of Justice League of America #254 and Watchmen #1, both dated September 1986 (source: dc.fandom.com), and the first panel of Watchmen #1, p. 9.

This attention to minute details of the physical world persists throughout the work, creating a sense of realism (what Barthes might call a “reality effect”) that points to the central thematic conceit of the series: “What would happen to our concept of the superhero if such crusaders were a real part of our world?” (Hughes 548). What may initially sound like an idle thought-experiment for comic book aficionados is arguably what lends the narrative its enduring popularity and relevance: Watchmen understands that the figure of the superhero has deep ties to culturally prevalent ideas of individual agency, the role of the state, and gender, to name just a few. But where many other superhero narratives gloss over these concerns by emphasizing the fantastical nature of their diegetic worlds and events, Moore and Gibbons make them the gravitational centre of their story (cf. Hughes, Piatti-Farnell, Prince). Watchmen is set in a fictionalized New York City of 1985, noticeably altered by some of the story’s premises, but still eminently recognizable in the cold-war anxiety of its advertisements and newspaper title pages. With one single exception, none of the characters actually possess supernatural powers. They are ordinary people who have chosen to don costumes and fight “bad guys”, for reasons that straddle the line between psychology and ideology: Whereas Walter Kovacs takes on the moniker of “Rorschach” in order to enforce his bigoted, reactionary ideal of law and order, Laurie Juspeczyk is pressured by her overbearing mother to follow in her footsteps as the acrobatic “Silk Spectre”. Reflecting this equal attention to the personal and the political, Watchmen’s twelve instalments alternate between chapters that advance the main plot around a global conspiracy involving the brutal murder of a retired superhero, and carefully constructed portraits of its principal characters.

A Story Only Comics Could Tell

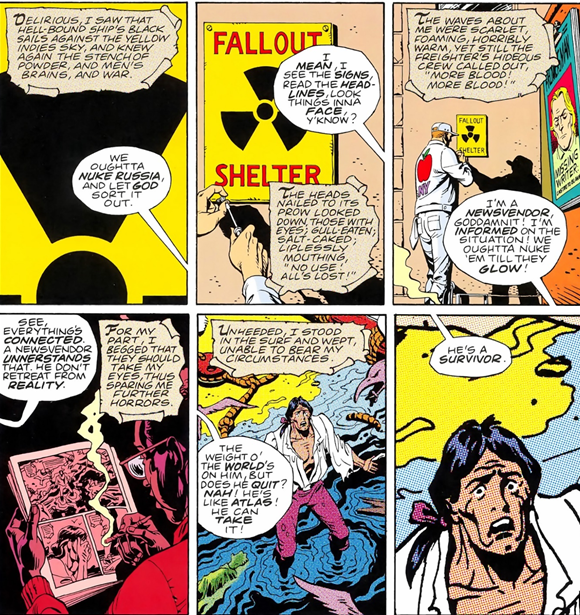

In addition to its thematic depth, Watchmen also remains an impressive demonstration of comics’ structural potential: The combination and direct juxtaposition of image and text makes comics more than the sum of their parts, with complex meanings arising from the various possible relationships between verbal and visual information (cf. McCloud 152pp.). Watchmen exploits this potential to deliver a multifaceted meta-commentary on the cultural significance and representational capabilities of comic books. One recurring subplot follows a newsvendor’s ramblings on current events while a boy sitting nearby reads “Tales of the Black Freighter”, a fictitious, mise-en-abyme pirate comic book. Starting with a seemingly superficial resemblance, the narration and images referring, respectively, to the world of Watchmen and “Black Freighter” begin to overlap, developing a parallelism between the plight of a stranded sailor and the threat of nuclear annihilation which points, once again, to the resonances of real-world politics in ostensibly fantastical pulp comics.

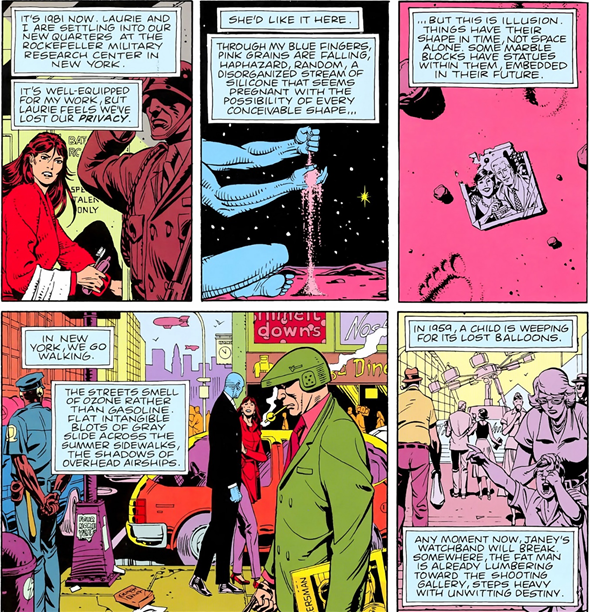

Equally prominently, Watchmen’s fourth chapter, “Watchmaker”, sketches a formalist poetics of comics through the perspective of Jon Osterman, alias “Dr Manhattan”: The only character with actual superpowers, Manhattan’s temporal perception is simultaneous rather than linear, with each moment of his life having its “shape in time, not space alone” (134). His musings on determinism and perception both allude to and utilize comics’ unique capability to represent time through spatially arranged images (cf. McCloud 104pp.), making readers aware of their movement through a space of simultaneously existing moments.

Perhaps the most dazzling display of formal complexity occurs in the series’ fifth instalment, titled “Fearful Symmetry” in a not-so-subtle allusion to William Blake1. Slightly more subtle is the central structural principle of the chapter, whose panel layouts and compositions are arranged for the second half of the issue to be an exact mirror-image of the first, with the central panel split between two pages to indicate the mirroring axis.

Conflicting Consequences

Its formal complexity and serious interrogation of its genre rendered Watchmen immensely influential in the comic book landscape and beyond: The first comic to win a Hugo Award for its contribution to science fiction, its dark tone and postmodern sensibility were to become a defining feature of mainstream comics in the following years, heralding what is sometimes called the “Dark Age” of comic books (Voger 6). It is also commonly credited with helping to popularize the concept of book-length collected series sold as “graphic novels”, although Moore, alongside other renowned comics writers such as Art Spiegelman, is critical of the term and its use for marketing purposes (cf. Millidge 135).

Throughout the twenty-first century, the legacy of Watchmen in popular culture has remained somewhat ambiguous. Zack Snyder’s 2009 film adaptation has become known for being almost slavishly devoted to its source material, to mixed reception (cf. Taylor). In contrast to this, more recent adaptations, or rather expansions, of Moore and Gibbons’ narrative have taken conflicting approaches to creatively appropriating their source material: On the one hand, starting in November 2017, Watchmen copyright holder DC published Geoff Johns and Gary Frank’s Doomsday Clock, another twelve-part series that merges the world of Watchmen with other DC characters such as Superman, effectively tying the graphic novel back into the very type of story it so adamantly deconstructs. On the other hand, Watchmen itself has recently become the object of subversive critique, most prominently in the form of HBOs 2019 television series of the same name: Presenting itself as a continuation of the graphic novel’s story, set 34 years later, the show “remixes” narrative and structural features of its source material, significantly re-framing some of its plot points and characters in the process. In this sense, Watchmen (2019) also constitutes a revisionist reading of Moore and Gibbons’ work, highlighting their neglect of “the multifaceted ways that superhero narratives intersect with the history of race and racism in America” (Johnson 399). With more conventional superhero films such as those mentioned above continuing to dominate the box office, it is clear that Watchmen has yet to exhaust its potential as a critical mirror to dominant cultural narratives of power and heroism.

Works Cited

Barthes, Roland. “The Reality Effect.” The Rustle of Language, trans. by Richard Howard, Hill and Wang, 1986, pp. 141-148.

Hughes, Jamie. “’Who Watches the Watchmen?’: Ideology and ‘Real World’ Superheroes.” The Journal of Popular Culture, vol. 39, no. 4, 2006, pp. 546-557.

Johnson, Thomas. “Appropriation Anxiety: Watchmen (2019).” Adaptation, vol. 13, no. 3, 2020, pp. 397-402.

McCloud, Scott. Understanding Comics. William Morrow, 1993.

Millidge, Gary Spencer. Alan Moore: Storyteller. Rizzolli Universe, 2013.

Moore, Alan, and Dave Gibbons. Watchmen. Colours by John Higgins, DC Comics, 2014.

Piatti-Farnell, Lorna. “‘For God’s sake, cover yourself’: sexual violence, disrupted histories, and the gendered politics of patriotism in Watchmen.” Journal of Graphic Novels and Comics, vol. 8, no. 3, 2017, pp. 238-251.

Prince, Michael J. “Alan Moore’s America: The Liberal Individual and American Identities in Watchmen.” The Journal of Popular Culture, vol. 44, no. 4, 2011, pp. 815-830.

Taylor, Aaron. “”The continuing adventures of the ‘Inherently Unfilmable’ book: Zack Snyders Watchmen.” Cinema Journal, vol. 56, no. 2, winter 2017, pp. 125-131.

Voger, Mark. The Dark Age: Grim, Great & Gimmicky Post-Modern Comics. TwoMorrows, 2006.