by Angelika Zirker

“… what is the use of a book […] without pictures or conversations?” – this is the question that Alice asks herself at the opening of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, while she is “sitting by her sister on the bank” (“Down the Rabbit-Hole”). No use at all, Lewis Carroll must have thought – and wrote a book for her, with a lot of pictures and conversations, narrating her adventures in a manuscript copy for Alice, the daughter of his Dean, Henry Liddell, at Christ Church, that she was given for a Christmas present in 1864: Alice’s Adventures Under Ground. The manuscript was circulated among friends to such acclaim that Charles Lutwidge Dodgson, as Lewis Carroll was called in his life as an Oxford don, commissioned John Tenniel, one of the most popular illustrators at the time, to provide professional “pictures” (i.e. based on woodblocks rather than drawn by hand) to accompany his “conversations” in Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, published in 1865. Six years later, in December 1871, Through the Looking-Glass and What Alice Found There would follow – 150 years later, this is the literary anniversary we would like to celebrate and pay tribute to this month.

“… what is the use of a book […] without pictures or conversations?” – this is the question that Alice asks herself at the opening of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, while she is “sitting by her sister on the bank” (“Down the Rabbit-Hole”). No use at all, Lewis Carroll must have thought – and wrote a book for her, with a lot of pictures and conversations, narrating her adventures in a manuscript copy for Alice, the daughter of his Dean, Henry Liddell, at Christ Church, that she was given for a Christmas present in 1864: Alice’s Adventures Under Ground. The manuscript was circulated among friends to such acclaim that Charles Lutwidge Dodgson, as Lewis Carroll was called in his life as an Oxford don, commissioned John Tenniel, one of the most popular illustrators at the time, to provide professional “pictures” (i.e. based on woodblocks rather than drawn by hand) to accompany his “conversations” in Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, published in 1865. Six years later, in December 1871, Through the Looking-Glass and What Alice Found There would follow – 150 years later, this is the literary anniversary we would like to celebrate and pay tribute to this month.

“All in a golden afternoon” – The Beginning of Alice’s Adventures

The original story, Alice’s Adventures Under Ground, goes back to a boating trip on the river Isis in Oxford on July 4, 1862. Lewis Carroll would take this up in the prefatory poem to Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland:

All in the golden afternoon

Full leisurely we glide;

For both our oars, with little skill,

By little arms are plied,

While little hands make vain pretence

Our wanderings to guide. (Carroll 2001: 7)

Dodgson’s friend the Reverend Robinson Duckworth was of the party, as were the three daughters of Dean Liddell: Alice, Edith and Lorina.

Imperious Prima flashes forth

Her edict “to begin it”:

In gentler tones Secunda hopes

There will be nonsense in it!”

While Tertia interrupts the tale

Not more than once a minute. (7)

“Thus grew the tale of Wonderland” (8) – and it continued to grow when, in 1871, Lewis Carroll decided to continue the story of Alice by sending her to the land behind the mirror for new adventures.

Through the Looking-Glass and What Alice Found There – The Chessboard Behind the Mirror

After the success of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, Lewis Carroll decided fairly early on to write a sequel. But it would take him some time to find an illustrator. John Tenniel at first refused to collaborate with Lewis Carroll again but then, after some negotiation, agreed to it anyway. He demanded more authority in the collaboration, and even suggested the omission of a whole chapter. After her encounter with the White Knight in Chapter 8, Alice was to meet “The Wasp in a Wig”. Tenniel found that the chapter didn’t “interest [him] in the least” (Gardner 2000: 297n), and that Lewis Carroll should cut it. It was only in the early 1970s that the galley proofs of the suppressed chapter were found; they were sold at Sotheby’s in 1974 and the chapter as such was first published in 1977.

Through the Looking-Glass and What Alice Found There was first published for Christmas in 1871 (dated 1872). The first two print runs (9.000 and another 6.000 shortly afterwards; see Carpenter and Prichard 1999: 527) were sold completely seven weeks later. While the figure of Alice links both the Wonderland story and the one behind the Looking-Glass, it has been suggested that, in fact, it was a different Alice who inspired Lewis Carroll’s idea to send the girl behind a mirror, namely his cousin Alice Raikes:

Dodgson gave her an orange and asked her in which hand she was holding it. When she said ‘The right,’ he invited her to stand before the mirror and tell him in which hand the girl in the looking-glass held the orange. ‘The left hand,’ came the puzzled reply. ‘Exactly,’ agreed Dodgson, ‘and how do you explain that?’ ‘If I was on the other side of the glass,’ said Alice Raikes, ‘wouldn’t the orange still be in my right hand?’ ‘Well done, little Alice,’ replied Dodgson, ‘the best answer I’ve had yet.’ (Hudson 1958: 20-21)

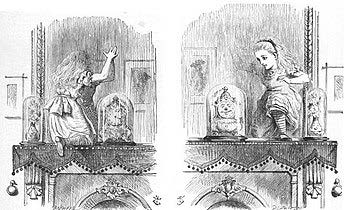

The story opens with Alice, her cat Dinah and her two kittens, a white one and a black. It is winter, the day before Guy Fawkes; Alice refers to the bonfires that are being prepared. It is snowing outside. While scolding the black kitten for undoing her worsted, she takes it up to the mirror above the chim-ney-piece and begins to talk about her “ideas about Looking-glass House” (Carroll 2001: 147):

She was up on the chimney-piece […]. And certainly the glass was beginning to melt away, just like a bright silvery mist. In another moment Alice was through the glass, and jumped lightly down into the Looking-glass room” (149). She finds herself on the other side of the mirror and starts to look around to discover “chessmen […] walking about, two and two! (150).

Through the Looking-Glass and What Alice Found There, like the Adventures in Wonderland, consists of twelve chapters, and it is after the first chapter and her entry into Looking-Glass house that Alice turns into a White Pawn and becomes part of the gigantic game of chess that is being played:

There were a number of tiny little brooks running straight across it from side to side, and the ground between was divided up into squares by a number of little green hedges, that reached from brook to brook. “I declare, it’s marked out just like a large chessboard! (172)

While all the moves make sense, the “alternation of Red and White” is not always “so strictly observed,” as Lewis Carroll noted in the Preface to the 1897 edition (Carroll 2001: 137). It is hence structured by a game of chess that, however, serves more as a demonstration of how to ‘queen’ a pawn (cf. Taylor 368). And this is how Alice, as Pawn, moves to become queen by chapter nine and wins in alto-gether eleven moves, when she takes the Red Queen.

In the course of her journey through the land behind the mirror, Alice meets “live flowers,” “looking-glass insects” who “won’t answer” to their names (182), Tweedledum and Tweedledee, the sleeping Red King, the disheveled White Queen, Humpty Dumpty, the March Hare and the Mad Hatter whom she knows from her Adventures in Wonderland – and so on. Recurring themes are names and the meaning of words, famously in the encounter with Humpty Dumpty who claims: “When I use a word […] it means just what I choose it to mean – neither more nor less.” (224). Nursery rhymes determine the action – for Humpty Dumpty as much as for Tweedledum and Tweedledee and the Lion and the Unicorn.

Apart from the chess game that is being played with Alice winning eventually, the ending of Alice’s dream in Through the Looking-Glass is very similar to the conclusion of her adventures in Wonderland: she refuses to play on and upsets the dinner-table, thereby getting hold of the Red Queen whom she starts to shake. “Shaking” leads over to “Waking”: these two short chapters contain the transformation of the Red Queen back into the black kitten. Thus her dream ends, and Alice finds herself back in the room where it began. The question “Which Dreamed It?” ends the narrative and thus her adventures: the last sentence invites the reader to join the guessing game “Which do you think it was?” (285).

Language and logic play even more important roles in Through the Looking-Glass than they did in the previous narrative (see Zirker 2008b): not only does language determine the plot in that nursery rhyme characters become alive and act according to their texts, but logic comes prominently into play with looking-glass reversals, such as eating biscuits to quench thirst running to stay in the same place (ch. 2), and handing around the cake before cutting it (ch. 7). On the whole, Through the Looking-Glass is the more ‘difficult’ book with a structure that is far more complicated than that of its predecessor. Although its basis is the structure of a game of chess, nonsense eventually wins over, and Alice can but wake up.

Life What Is It but a Dream?

Unlike Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, Through the Looking-Glass not only has a prefatory poem but also a concluding one, so that two poems frame the narrative. In the poem preceding the narra-tive, the speaker looks back not to one particular day but to the complete childhood of the “dream-child,” now grown up. In a similar vein, the concluding poem also refers back to the child and her ad-ventures in Wonderland:

A boat beneath a sunny sky

Lingering onward dreamingly

In an evening of July—

Children three that nestle near,

Eager eye and willing ear,

Pleased a simple tale to hear— (287)

He foregrounds how his memory of Alice will not fade, and that also the story will continue to be told:

Children yet, the tale to hear,

Eager eye and willing ear,

Lovingly shall nestle near.

In a Wonderland they lie,

Dreaming as the days go by,

Dreaming as the summers die:

Ever drifting down the stream—

Lingering in the golden gleam—

Life, what is it but a dream? (287)

Because the story will continue to be narrated, the memory of Alice and her adventures will be kept alive, and even the dream is repeated. At the same time, the final question refers back to the Red King, who is found asleep during Alice’s encounter with Tweedledum and Tweedledee (ch. 4) and who, according to them, not only dreams of Alice but on whom her existence depends: “‘If that there King was to wake,’ added Tweedledum, ‘you’d go out – bang! – just like a candle!’” (198).

It was even before writing the Alice books that Carroll was intrigued by and fascinated with the relation of dream and life. In a diary entry from February 1856 he writes:

Question: when we are dreaming and, as often happens, have a dim consciousness of the fact and try to wake, do we not say and do things which in waking life would be insane? May we not sometimes define insanity as an inability to distinguish which is the waking and which the sleeping life? We often dream without the least suspicion of unreality: “sleep hath its own world,” and it is often as lifelike as the other. (Diaries 1993-2007: 2, 38)

The ability to distinguish between dream-world and reality is lost; at the same time, the verbatim quote from Byron’s poem “The Dream” refers to the existence of a different world in dreams. Within the fantastic worlds created, the dream becomes reality, and the boundaries between reality and imagi-nation are blurred.

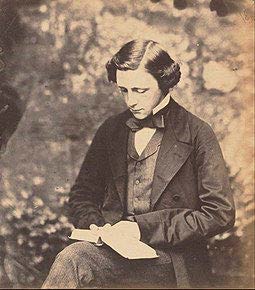

The Oxford Don – Who Dreamt It All

Charles Lutwidge Dodgson was born on January 27, 1832 at Daresbury parsonage, Cheshire. As the eldest child, he was partly in charge of family entertainment and, at the age of thirteen, inaugurated the first of a series of family magazines for his siblings, under the name of Useful and Instructive Poetry, followed by The Rectory Magazine, The Rectory Umbrella and Mischmasch. His literary interest continued during his time at school and later at university: in 1851, he entered Oxford and studied at Christ Church College; it was also there that he worked as a Lecturer in Mathematics from 1855, a position he held until 1881; he then resigned his post to focus on his writings, both in the field of mathematics and as a literary author.

Charles Dodgson became Lewis Carroll in 1856, when he decided that he needed a pseudonym for the publication of “Solitude” in The Train: “Wrote to Mr. Yates [editor of The Train], sending him a choice of names, 1. Edgar Cuthwellis (made by transposition out of “Charles Lutwidge”), 2. Edgar U. C. Westhill (ditto), 3. Louis Carroll (derived from Lutwidge = Ludovic = Louis, and Charles), 4. Lewis Carroll (ditto)” (February 11, 1856; Diaries 1993-2007: 2, 39). From that time, he published all his literary works under the name of Lewis Carroll; his mathematical writings, however, continued to appear under the name of Charles Lutwidge Dodgson.

Lewis Carroll is still famous today for his Alice books: By the time of his death in 1898, 180.000 copies of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland had been sold. The story is a classic today, translated into more than sixty languages, and one of the most popular books ever written, besides Shakespeare and Bunyan’s The Pilgrim’s Progress. Like its predecessor, Through the Looking-Glass was highly popular at its publication; the first Alice book, however, seems to have been more lastingly successful: frequently, only individual scenes from the second narrative are included in dramatisations and film versions of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. When in 2006 the British were to nominate their ‘national icons’, Alice ranked among the first twelve (other icons are Stonehenge, Punch & Judy, the FA Cup, the King James’s Bible). The narratives go back to the imagination of one man, who dreamt it all – and who, in the words of Virginia Woolf, not only could return to the world of childhood, but who “could re-create it, so that we too become children again” (Woolf 1966: 254).

Works Cited

Carpenter, Humphrey; and Mari Prichard (1999). The Oxford Companion to Children’s Literature. Oxford: OUP.

Carroll, Lewis (2001). The Annotated Alice. Ed. Martin Gardner. London: Penguin.

Carroll, Lewis (1993-2007). Lewis Carroll’s Diaries: the Private Journals of Charles Lutwidge Dodgson. Ed. Edward Wakeling. 10 vols. Luton: The Lewis Carroll Society.

Hudson, Derek (1958). Lewis Carroll. London: Longmans, Green & Co.

Taylor, A. L. (1971). “Chess and Theology in the Alice Books.” Lewis Carroll: Alice in Wonderland. A Norton Critical Edition. Ed. Donald J. Gray. New York: Norton, 365-77.

Woolf, Virginia (1966). “Lewis Carroll.” Collected Essays. 4 vols. London: The Hogarth P, 1: 254-55.

Zirker, Angelika (2007). “Lewis Carroll.” The Literary Encyclopedia. First published 23 August 2007 [https://www.litencyc.com/php/speople.php?rec=true&UID=5088, accessed 09 November 2021.]

Zirker, Angelika (2008a). “Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland.” The Literary Encyclopedia. First pub-lished 20 May 2008 [https://www.litencyc.com/php/sworks.php?rec=true&UID=9725, accessed 09 November 2021.]

Zirker, Angelika (2008b). “Through the Looking Glass and What Alice Found There.” The Literary Ency-clopedia. First published 20 May 2008 [https://www.liten-cyc.com/php/sworks.php?rec=true&UID=9726, accessed 09 November 2021.]