More Context and Less: A Response to Lena Linne and Burkhard Niederhoff

Carolin Hahnemann

Published in Connotations Vol. 28 (2019)

Abstract

In her response to Lena Linne and Burkhard Niederhoff’s article on Alice Oswald’s poem “Memorial,” Carolin Hahnemann addresses how a wider understanding of recontextualization in relation to the poem’s similes unlocks new interpretive paths.

1. Preamble

As a digital, open-access publication, Connotations is particularly well-suited to serve as the venue for a multi-disciplinary exchange of ideas, such as the discussion of Alice Oswald’s poem Memorial: An Excavation of the Iliad has turned out to be. Upon its publication, first in the United Kingdom in 2011 and then in the United States in 2012, the poem was widely reviewed in Anglophone newspapers and poetry magazines. More recently, it has become the subject of scholarly articles, mainly in the area of Classics, but also in Theater Studies, Eco-Criticism, and English Literature. In order to facilitate this engagement across different types of publications and disciplines further, I include at the end of my response an extensive list of reviews, interviews, and scholarly treatments of Memorial. It is my hope that my response will, in its turn, inspire other responses and thus provide a stimulus to further discussion of this remarkable poem.

In addition to transcending the disciplinary boundaries of more traditional journals, Connotations also provides a significant advantage due to its particular publication format, which allows for a seed article to be followed up by a series of linked responses. Consequently, I ask readers of this response who are not familiar with the poem to consult the description offered in the seed article, only one click away.

2. Overview

In their article, “‘[M]emories and similes laid side by side’: The Paratactic Poetics of Alice Oswald’s Memorial,” Lena Linne and Burkhard Niederhoff explore Alice Oswald’s practice of lifting Homeric similes from their original context in the Iliad and integrating them, in adapted form, into the long middle portion (henceforth labeled Part B) of her poem Memorial. They state that, by replacing Homer’s plot with an unconnected sequence of poetic obituaries for the casualties of the Trojan War whose deaths are recounted in the epic, the poet poses herself “the task of producing a new kind of coherence” between the transplanted similes and their new context. Thus, they conclude, Oswald’s poem constitutes “an act of creation by decontextualization and recontextualization” (22).

In what follows, I seek to inflect this conclusion in two seemingly opposite ways. First, I argue for a broader definition of “recontextualization.” For Linne and Niederhoff, the new context of a simile in Memorial consists solely of the preceding obituary, but a simile may connect in a meaningful way with other passages of the poem as well. Second, I draw attention to a group of similes where the authors’ concept of “recontextualization” does not apply, because the simile follows a list of names rather than a verse obituary. This observation leads to an investigation of Oswald’s extensive and innovative use of blank space as a constituent element in Memorial, where the blank spaces do not merely create a generic void but rather evoke a specific context of missing material. In an earlier article on the poem, I showed that the lamentation for the dead in Memorial is radically inclusive in that it records the loss of life of the men fighting on both sides without distinction, and even reaches beyond the human realm by including an obituary for a horse killed in combat (Hahnemann, “Book” 18-26). In the final section of the present article, I argue for a third type of inclusiveness by suggesting that Memorial commemorates not only the 215 dead who are named explicitly on its pages, but extends also to the many casualties of the Trojan War not mentioned in the Iliad, and perhaps even to the casualties of all wars since, down to our own time.

3. Argument and Findings of the Seed Article

At the center of Linne and Niederhoff’s article stands a series of test cases in which the authors interpret seven similes from Memorial, each in connection with the obituary that precedes it in the modern poem on the one hand, and with reference to its original context in the ancient epic on the other (25-38):1)

| Simile in the Iliad | Context in the Iliad | Preceding Obituary in Memorial | |

|---|---|---|---|

| a. | wind on the sea and on a cornfield (2.144-48) | Agamemnon’s exhortation of the Greek army | Protesilaus (9) |

| b. | a dog chasing a deer (22.189-92) | Achilles chasing Hector around Troy | Diores and Pirous (12) |

| c. | a little girl crying and begging to be picked up (16.7-10) | Patroclus begging Achilles to help the Greeks | Scamandrius (14) |

| d. | a woman weighing wool (12.433-35) | a stalemate in the fighting around the Greek camp | Acamas (22) |

| e. | oaks withstanding the wind (12.132-34) | Leonteus and Polypoetes defending the Greek wall | Ilioneus (49-50) |

| f. | generations of leaves (6.146-48) | generations of men | Hector (68-69) |

| g. | a shooting star (4.75-77) | Athena descending to the battlefield | —— |

In their discussion of these similes, the authors discern several patterns in the way Oswald departs from her Homeric model. To begin with, they note that in the Iliad the similes serve to illustrate a variety of events while in Memorial, whose “narrative” consists purely of obituaries, all of them come after the description of a death (a: 28; e: 33). As a result, the contrast between the world of the similes and the world of the narrative, although it exists also in Homer, emerges more starkly in Memorial: whereas the similes for the most part describe ordinary events that happen again and again, the obituaries focus on the extraordinary moment when the life of a unique individual is irrevocably lost (d: 32; e: 34). At the same time, Oswald tends to shift the focus of the narrative from the victorious warrior to the man killed, which lends her poem the tone of a lament (b: 29 with n12; e: 33).

In a second set of observations, the authors note that the point of contact between tenor and vehicle, technically known as the tertium comparationis, is less clear in Oswald’s poem than in Homer’s, since she eschews the use of signposts and different simile markers, opting instead for a looser link by opening each simile with the word “like” (a: 26; b: 30; e: 33). At the same time, however, in many cases she also creates subtle connections between an obituary and a simile by reshaping the Homeric material so as to give rise to a shared concept (a: 26; c: 30; e: 33-34), which can be reinforced by verbal echo (c: 30-31; d: 32; f: 35). Consequently, in some instances the meaningful similarities Oswald employs to tie together obituary and simile are shot through with equally meaningful contrasts, for example in the juxtaposition of a warrior’s death on the battlefield with a peaceful domestic scene (c: 31; d: 32; e: 35).

Finally, Linne and Niederhoff propose a pattern of a different kind, arguing that certain similes can be interpreted as meta-poetic, self-reflexive statements about Memorial as a whole. They suggest this reading apropos of the similes framing Part B of the poem— the wind simile (quoted and discussed below on pp. 49-51), and the simile about the generations of leaves and men—and return to it in their discussion of the simile about the shooting star at the end of Part C, the very last simile in the poem (a: 26-27; f: 36-37; g: 37-38). In my opinion, this pattern, which lacks an analogue in the Iliad, is especially intriguing and warrants systematic study. Similes relevant to such a study could include the one about the olive wand which “became a wind-dictionary [that] could speak in tongues” (27-28), an evocative neologism which Mira Rosenthal borrowed for her description of Memorial as a whole. Given the poem’s frequently noted similarity in format and content to an inscribed tombstone or casualty list (e. g. Green; Cole; Rosenthal; Hahnemann, “Book” 5-14; Schein 156), another simile with a potentially self-reflexive dimension is the one about “a stone [that s]tands by a grave and says nothing” (43). The recurrence of failed speech acts in these self-reflexive similes also makes for a fascinating link to Stephe Harrop’s view that Memorial casts death primarily as a loss of the human faculty to speak.

Due to the somewhat subjective nature of the connections proposed by Linne and Niederhoff, readers will disagree as to which ones they find convincing, and one may hope that other scholars will feel inspired to continue, complement, or contradict some of the lines of thought they have broached. Regardless of such disagreements about individual instances, however, the authors’ exploration of the connections that tie a particular simile to the preceding obituary forms a valuable contribution to the growing body of evidence supporting the view that the placement of the similes in Memorial is meaningful and worthy of investigation. That this should be so is by no means a foregone conclusion. To the contrary, several of the poem’s early reviewers complained that, removed from their original context, the similes no longer make sense; William Logan, for example, whose sentiment is shared also by Guriel and Green, describes Oswald’s method as a “rough-and-ready recycling” which “too often […] destroys the force, and the cunning, of the Iliad,” resulting in a “Frankenstein transplant.”

More recently, however, reviewers as well as scholars have been adducing insights that contradict these indictments, and the findings of Linne and Niederhoff fit well into this framework. The shift of focus from victor to victim, for instance, was first observed by Elizabeth Minchin, who specifies that in reworking the Iliadic material for her obituaries, Oswald erases all references to the victor’s gloating over his success and in fact often does not even provide his name (209, cf. also Pache 176). Linne and Niederhoff extend this insight by showing that the same shift applies also to the similes (29 with n9). Their observation, in turn, constitutes an important link to Oswald’s habit of underlining the opposition between the genders in the similes by consistently marking the victims of violence as female and the aggressors as male (Hahnemann, “Feminist”, forthcoming).

4. Problems of Recontextualization I: The Boundaries of Context

Surprisingly for a study focusing on the role of the similes in Part B of Memorial, Linne and Niederhoff offer no discussion of the remarkable fact that most of the similes are repeated.2) Critics have described the effect of the repetitions in a variety of interrelated ways, stating that they create the solemn, even otherworldly atmosphere associated with a state of trance or prophetic utterance (Kellaway; Womack, “Memorial”); that they allow the readers/listeners to absorb the image first cognitively and then emotionally, while also granting them a respite from the grief induced by the poem as well as its fast pace (Jaffa 19; Crown; Rosenthal); that they serve as an element of music and a source of pleasure (Hahnemann, “Book” 4-5; Minchin 212n31). Adopting a more philosophical point of view, Teju Cole explains them as a “clarifying echo [that] invites the reader to place, one more time, each death into its proper natural context of dispersal and oblivion” (15), and David Farrier sees them as a “spectral echo in Derrida’s sense of a moment that is both ‘repetition and first time’” (4).

Most relevant to the investigation undertaken by Linne and Niederhoff, however, is a statement by Oswald herself. While the authors limit their analysis to a selection of similes and the preceding obituaries, the poet cites as one of her intentions in repeating (almost all of) the similes a desire to encourage the reader to think of them as connecting forward as well as back: “the first one links to the life behind it, and the second one links to the one in front. They’re like [a] kind of swing doors” (Jaffa 19). Corinne Pache (182-85) provides a compelling example of such a double-headed reading in her study of the obituaries for the brothers Polydorus and Lycaon, which in Memorial appear less than forty verses apart and are each preceded by a sea simile and followed by a lion simile. Moreover, as she points out, the mention of Polydorus’ bereft father in his obituary resonates with the image of a male lion leading his cubs in the accompanying simile, while the central role given to Lycaon’s traumatized mother in his obituary is picked up by the plight of a female lion whose cubs have been stolen. As these insights show, a broader definition of the new context into which Oswald has transplanted a simile can lead to the discovery of larger structural patterns in the poetic design of Memorial.

The double-headed approach suggested by Oswald and exemplified by Pache also lends support and nuance to Linne and Niederhoff’s provocative interpretation of the first simile in the poem (9-10):

Like a wind-murmur

Begins a rumour of waves

One long note getting louder

The water breathes a deep sigh

Like a land-ripple

When the west wind runs through a field

Wishing and searching

Nothing to be found

The corn-stalks shake their green heads

(repeated)

Since this simile follows after the obituary for Protesilaus, the authors suggest that there is “a kind of dialogue between the wind on the one hand and the sea and the cornfield on the other—as if the wind is saying, ‘What about Protesilaus?’, to which the waves respond with a deep sigh, and the cornstalks by shaking their heads, indicating that the wind is searching for a man who no longer can be found” (27). Indeed, it seems especially appropriate that the wind should search for Protesilaus among the sea waves, since this hero was killed “jumping to be first ashore” (9) when the Greek armada made its landfall at Troy. Complementarily, the second portion of the double simile with its mention of the corn-stalks can be related to the two subsequent obituaries for Echepolus and Elephenor if we recall a passing remark in the Iliad which suggests that the battlefield beneath the walls of Troy had formerly been a cornfield (21.602-03). The knowledge that the plain where of late Echepolus “mov[ed] out and out among the spears” (10) had, in times of peace, bristled with ears of corn instead of the blades of spears also creates a tension between the simile and the obituary in Memorial akin to the bitter irony inherent in the Homeric simile—not used by Oswald—that compares the Greek and Trojan warriors cutting each other down on this very plain to two lines of reapers mowing down a cornfield (11.67-69).

Readers might hesitate to accept the reading proposed by Linne and Niederhoff because it attributes to this simile a very specific connection to the man mourned in the preceding obituary while most of the other similes in Memorial tend to be more generic. We should remember, however, that the obituary for Protesilaus itself constitutes an exception to a rule, seeing that he is the only casualty included in Memorial whose death does not occur during the period of the war recounted in the Iliad. Moreover, the image of the wind going in quest of a dead man in much the same manner as the thoughts of his surviving relatives might do fits well with Oswald’s habit of describing nature in anthropomorphic terms. Even the idea of a kind of near-verbal dialogue envisioned by Linne and Niederhoff between the wind and the water that “breathes a deep sigh” and the corn-stalks that “shake their green heads” is not far-fetched, since it receives support from a passage near the end of Part B in which an element of the natural world clearly joins in the human lament for the dead. Here the river Scamander causes the Trojan women doing their laundry on its bank to think of their dead relatives who died in its waters (67):

Women at the washing pools

When they hear the river running

Crying like a human through its chambers

They remember THERSILOCHUS…

They remember MYDON…

Homer refers to the washing pools as a landmark that Achilles and Hector pass in their mortal race around Troy: there “the wives of the Trojans and their lovely / daughters washed the clothes to shining, in the old days / when there was peace, before the coming of the sons of the Achaians” (22.154-57). Oswald, by contrast, has shifted the mention so that it now forms part of the obituary for the multitude of Trojans Achilles killed on his rampage prior to going after Hector. More importantly, she has shifted the chronological perspective as well. In the Iliad, the mention of the washing pools occasions a glance backward in time; at the very moment when the drama of the battlefield is about to reach its climax, the epic drives home the horror of war by calling to mind a peace-time scene. Thus Homer emphasizes the contrast between a past lived in peace and a present marred by war. In Memorial, however, the reverse is the case: here the washing happens in the present while the carnage is a memory from the past. Evidently, for the Trojan women in Memorial, time has come to a stand-still with the result that the distinction between past and present has been erased for them, just as it has for Laothoe, who relives the death of her son every time she looks at the river where he “was washed away” (66). Nor does the grief for the lost human life persist only in the minds of the human survivors; rather, it has been inscribed on the landscape in the crying river and, as Linne and Niederhoff suggest, the wind’s futile quest for the dead.

5. Problems of Recontextualization II: The Absence of Context

Oswald has composed verse obituaries for about half of the casualties, while the rest appear only as names in list format (21, 24, 28, 36, 38, 40, 41, 46, 52, 53, 56, 61, 62, 65). Consequently, Linne and Niederhoff’s method of seeking for connections within a simile-obituary pair cannot always be applied, because some similes are preceded and/or followed by a bare list of names. It appears, then, that coherence is not Oswald’s primary concern; indeed, quite the opposite. According to a statement she made in an interview, she sought to recreate in Memorial her own—highly idiosyncratic—experience of Homer’s poetry as “things just being little separated blocks next to each other—but not hierarchical” (Jaffa 19). While readers may hesitate to accept Oswald’s image as an apt description of the narrative fabric of the Iliad, it works very well for Memorial, where each chunk of text—be it an obituary, a list of names, the first or the second iteration of a simile—is set off from its surroundings by a bit of “nontext” in the form of a blank space on the page. Later in the same interview, Oswald makes this very point when she says about the structure of Memorial that, instead of “a whole shape spread[ing] over the whole poem, [she] wanted it to have these chopped, side-by-side things” (Jaffa 19). Thus, as Linne and Niederhoff indicate in the title of their article, it is a defining characteristic of Memorial that its constituent elements are placed “side by side”, but it is equally important that they have been separated and chopped apart.3)

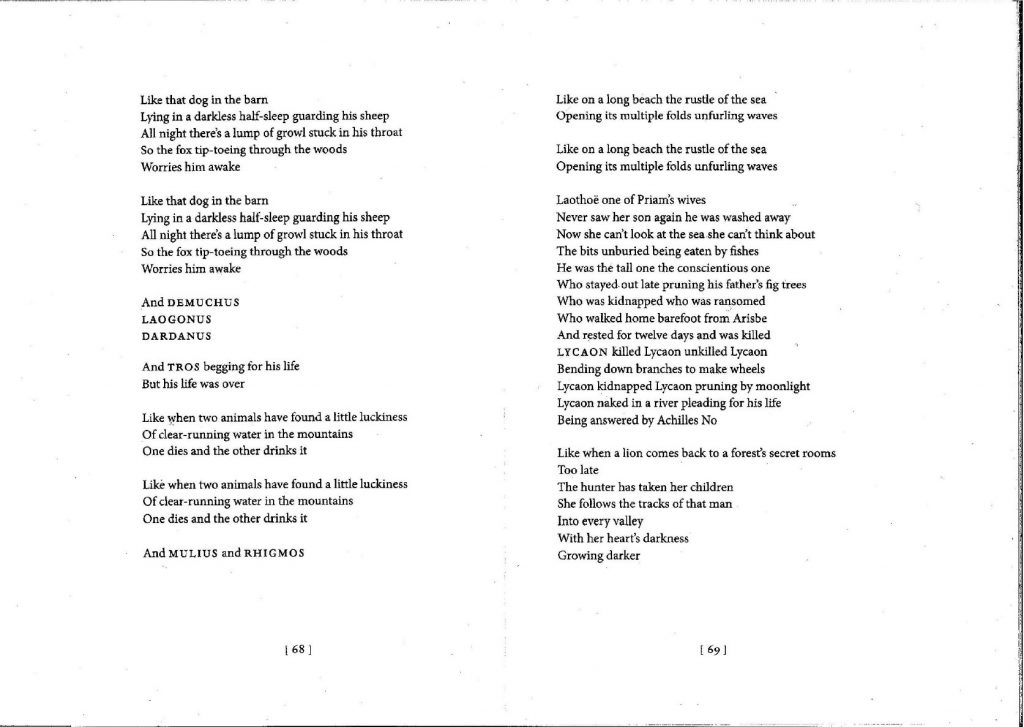

Img. 1: Blank spaces turn each list, obituary, and simile in Memorial into a discrete chunk of text.

IOswald presents the chunks of texts in Memorial in such a way as to give all equal importance, but she helps the readers/listeners to recognize a pattern in their relationship to each other by means of two different connectors: “and” and “like.”4) The fact that she uses “like” to introduce almost all of her similes has raised the eyebrows of Logan and other grammar mavens among her critics, because in many instances the correct connective would be “as.” But switching back and forth between “like” and “as” would have compromised the effect of the repetition, and moreover, as Oxford Professor of Poetry Simon Armitage demonstrates in a lecture on the similes of Elizabeth Bishop, a more flexible use of “like” has precedent not only in colloquial speech but also in modern poetry. Still, Linne and Niederhoff’s conclusion holds true: Oswald’s use of the word in Memorial is radical in its looseness. Picking up on Oswald’s own metaphor from her introduction, in which she calls Memorial a “bipolar” poem (in the sense the term is understood in physics rather than in psychology), we may think of the word “like” as establishing a kind of force field between the world of the battlefield on the one hand, and the world of nature and peacetime activity on the other.

In contrast to the syntactic and semantic looseness with which Oswald uses the word “like” at the beginning of the similes, she gives the connector “and” at the start of obituaries and lists of names a very specific function. Since “and” does not usually begin a sentence, its occurrence as the first word of a chunk of poetry no fewer than twenty-six times throughout Memorial is remarkable.5) This special type of “and” occurs both at the start of obituaries (63) and of lists (61):

And IPHITUS who was born in the snow

Between two tumbling trout-stocked rivers

Died on the flat dust

Not far from DEMOLEON and HIPPODAMASAnd HIPPOTHOUS

SCHEDIUS

PHORCYS

LEOCRITUS

While translators of Homer will sometimes start a sentence with “and” in imitation of the ancient epic’s narrative style, which links almost every sentence to the preceding one by means of a connecting particle, Oswald employs the word as a link not to what comes immediately before it, but as a bridge to the previous death across the intervening blank spaces and simile. This interpretation is confirmed by her even more unconventional use of “and” as the last word of a list (21), whereby she clearly signals to the readers/listeners that more entries are yet to follow. In this manner, then, she ties together the deaths on the battlefield into a continuous, albeit interrupted sequence.

As Elizabeth Minchin reminds us, lists are an important element in the Iliad as well as in Memorial (204-07). The most notable example is the so-called Catalog of Ships, a survey of the contingents of the Greek and Trojan forces along with their leaders early on in the epic, which, according to the late novelist Umberto Eco, constitutes the prototype for one of two fundamental artistic principles. As he outlines in the book accompanying his 2009 exhibit, The Infinity of Lists, at the Louvre, the description of Achilles’ shield near the end of the Iliad exemplifies a “closed system” or “form”, used to depict “a thing understood” by means of a “poetics of the everything included.” By contrast, a list or catalog establishes an “open system” by means of a “poetics of the etcetera,” in an attempt to grapple with the unknown by listing its (always infinite) attributes (7-18). The reason why Eco sees the Catalog of Ships as an instance of this latter group lies in the fact that only the number of the leaders listed is finite, whereas the number of the implied followers is unknown. Although it seems doubtful that an ancient reader would have shared Eco’s perception of the Catalog of Ships in the Iliad as incomplete because it does not list the common soldiers, it raises an interesting question in regard to Memorial.

Since the sequence of deaths starts with Protesilaus, who is said to have been “the first to die” (9), and ends with Hector, whose death and funeral are widely known to conclude the Iliad, readers/listeners may well come away with the impression that Memorial reflects the evidence contained in its ancient model completely and correctly. It takes a meticulous, not to say pedantic juxtaposition of the two works to reveal some subtle deviations (Hahnemann, “Book” 29). More importantly though, Oswald pursues a strategy of including persons in her poem who are not mentioned in the Iliad by making their absence conspicuous. For example, by saying about a dead man that “nothing is known of his mother” (10), she draws attention to the fact that in the epic the account of this hero’s family, like that of most others, makes reference to his father but keeps silent about his mother. Thus, “under Oswald’s gaze, apparent absence takes on the quality of presence” (Farrier 7). Arguing along similar lines, in the remainder of this article I suggest that the blank spaces in Memorial serve not only to create “little separated blocks,” but also to leave room in the interstices for casualties who cannot be mentioned by name.

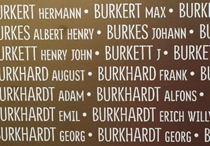

Image 2: Like Memorial, contemporary monuments often make use of conspicuous absences; here the subterranean set of empty shelves commemorating the Nazi book burning on Bebelplatz in Berlin. © Carolin Hahnemann

6. The Nameless Dead

In all there are three groups of nameless dead whom Oswald conjures by means of clues in the surrounding text to become part of the poem in this negative way. The first group consists of the very men whom Eco had in mind when he pronounced the Iliadic Catalog of Ships incomplete: the warriors of lower social status as opposed to the heroic leaders. Oswald makes oblique reference to them when she mentions that Protesilaus commanded a contingent of “forty black ships” (9). At first, one might pass over this detail as a gratuitous embellishment intended to lend the modern poem a bit of Homeric flavor, but the fact that it occurs a second time only one page later in the obituary for Elephenor (10) argues against such an easy dismissal. If we follow Thucydides’ famous estimate regarding the average number of warriors per Greek ship in the Trojan War, each of these leaders had no fewer than 3400 men under his command. Evidently, then, the conventional label that dubs Protesilaus and Elephenor “minor warriors,” for example in the title of Gisela Strasburger’s important study, is misleading; although they occupy only a handful of verses in the Iliad, they are nevertheless members of the privileged class with high social status. Even if we assume that these leaders, fighting in the front row as the heroic code demanded, died in disproportionately greater numbers than their followers, the double mention of the forty ships at the start of Memorial leads the readers/listeners to suspect that, besides the named leaders, many of their nameless followers must have died as well. This inference is confirmed later in the poem in the obituary for the Thracian King Rhesus, where we learn that “[t]welve anonymous Thracians were killed in their sleep / Before their ghosts had time to keep hold of their names” (31). The pointed reference to the dead men’s namelessness draws attention to, and thereby transcends, a limitation to the feasibility of Memorial as a commemorative endeavor: the roll call of the dead presented in the modern poem cannot be complete because in many, even most, cases the dead man’s name is not recorded in its ancient source.

Close attention to the way Oswald has shaped the first two obituaries also reveals a second group of dead that are conspicuously absent from the poem. The number of casualties listed in the Iliad is restricted both in terms of the narrative lens, which always focuses on just one or two areas of the battlefield while making it clear that much killing is going on simultaneously elsewhere, and of narrated time, since the epic covers only a brief period near the end of the Trojan War. Oswald goes beyond the chronological boundaries of the plot of the Iliad when she includes, exceptionally, an obituary for Protesilaus, whose death took place when the Greek fleet first landed at Troy at the onset of the war. Already in the next pair of obituaries, however, she specifies that Elephenor was killed “in the ninth year of the war” (10) and, resorting again to her strategy of emphasizing a detail through quick verbatim repetition, she reiterates the phrase in the obituary of Simoisius (11). Obviously, in the intervening years of continuous warfare many Greeks and Trojans must have died, and although we can learn nothing about them from the Iliad, their absence is made palpable and thus becomes a kind of presence in Memorial.

Finally, the series of casualties in Memorial transcends the confines of the Iliad also in the other direction, namely by reaching into the future. Admittedly, the Iliad, too, foreshadows future events, most importantly Achilles’ imminent death, which comes into view with ever greater precision as the epic progresses. In Memorial, thanks to Oswald’s omission of the Homeric plot, the narrative never turns away from the battlefield, so that the inexorably mounting death count eventually threatens to overwhelm not only the audience but the narrator as well. Toward the end of Part B, in the midst of a sequence of obituaries that get increasingly shorter until they are whittled down to a list of names, the narrator exclaims meta-poetically: “And LYKOPHRON / And KLEITOS it goes on and on” (53). Once again, Oswald repeats the key phrase soon after, in this case on the very same page, now embedded into the subsequent simile: “every living twig / Is wiped out white with snow it goes on and on.” It seems that, just as it is impossible to make out the features of a landscape covered by snow, so also the narrator can no longer keep up with the killings. In light of this exclamation, it is not surprising that after sixty pages chronicling 215 deaths in Part B, in Part C the fabric of the poem thins into a sequence of uninterrupted similes, printed one to a page, and then ceases altogether.

Just prior to this final vanishing act, however, the poem contains a pregnant pause in the form of a large blank space: after the obituary for Hector, the rest of the page is left empty both in the English and in the American edition. Linne and Niederhoff mask this fact when they state that the simile of the generation of leaves “accompanies” Hector’s obituary (35). But the empty space deserves to be taken seriously, and all the more so since it has a counterpart at the end of the litany of names in Part A, after the final entry “HECTOR”: “[T]he blank page after those two final bold syllables is heartbreaking,” comments Womack (“Memorial”), “The rest is silence.” Indeed, Hamlet’s last words capture well the impression of the blank space on the audience at a recitation of Memorial, who will experience it as a pause. For the readers, however, who encounter the blank space visually, it may bring to mind the uninscribed surfaces on a new kind of war memorial that has emerged lately in the United States in response to the War on Terror.

Monuments like the Middle East Conflicts Wall in Marseilles, IL (permanent version dedicated in 2004), the Hillcrest War on Terror Memorial in Hermitage, PA (dedicated in 2005), and the Middle East Northwood Gratitude and Honor Memorial in Irvine, CA (permanent version dedicated in 2010) share several features in common: they all originated through private initiatives, they list the US soldiers who have died in the conflict in the Middle East, and, most importantly, they leave room for ongoing updates with new names to be added. This last feature in particular sets them apart from the countless monuments containing casualty lists that dot cities and cemeteries all over the Western world; as a rule, those war memorials were erected not during the conflict in question but after it had been concluded. In fact, in the United States the law specifically mandates a ten-year wait period after the end of a military conflict before it can be commemorated in a monument on the National Mall. It is all the more remarkable, then, that in August of 2017, Congress decided to waive this requirement in the case of a proposed national memorial for the Global War on Terror, thereby allowing planning and preparations to commence immediately. The implication of this decision is clear. What might once have been regarded as a series of several separate wars is now being viewed as a single drawn-out conflict flaring up again and again in different locations. Thus the smooth surfaces waiting to receive the names of future casualties on this new kind of memorial bear grim testimony to the conviction that, as far as the War on Terror is concerned, there is no end in sight.

Can we draw a similar conclusion about the Trojan War from Oswald’s choice to leave a bigger-than-usual blank space at the end of Part B of Memorial? We know from the mythological record that many more Greeks and Trojans were killed after Hector, and it is only reasonable to think of the later victims as a third group of nameless casualties in analogy to the two groups proposed above. But maybe that is not enough. More radically, the phrase that the killing “just goes on and on” can be taken as an invitation to think of the blank space at the end of Part B as a place-holder for the names of every man killed in war since that first mythical conflict, the Trojan War, until today.

Image 3: Inscribed stele of the Northwood Gratitude and Honor Memorial in Irvine, CA, with space left blank for the names of future casualties to be added. © Sukhee Kang

The idea that Oswald might have intended the blank space at the end of Part B as a way to connect the Trojan War to later military conflicts down to our own time fits well with other aspects of her poetic practice. For example, she injects splinters of the modern world into the obituaries and similes by using anachronisms such as a “lift door” (13), “tin-open[ing] (17), astronauts (32), parachutes (42), and a motorbike (69). Moreover, as we saw in the discussion of the women by the washing-pools above, Oswald’s presentation of time is kaleidoscopic. Pache sensitively explores the poet’s technique of connecting the dead from the past to the audience in the present, including her use of narrative tenses and instances in which the narrator addresses the audience (175-78). For example, Protesilaus’ death happened in a distant past “thousands of years” ago (9), while “the stump of Hypsenor’s hand [that l]ies somewhere on the battlefield” (16) seems frozen in time. Above we encountered the latter as the perspective of the traumatized relatives, townspeople, and the local landscape, but it even extends to the reader, who becomes a vicarious witness to the violence when being told that “you can see” the hole in Echepolus’ helmet where the fatal weapon entered his skull (10). Cumulatively, these techniques add to the poem’s overwhelming emotional effect; by bringing the deaths from the mythical past into the present in this way, Oswald renders it impossible for the readers/listeners to keep their distance.

As is clear from the above analysis, Oswald’s process of creation in Memorial at times constitutes “an act of creation by decontextualization and recontextualization,” as Linne and Niederhoff suggest (22), but at other times it remains an act of creation by decontextualization without recontextualization. Unquestionably, the most important instance of the latter strategy lies in the poet’s omission of the epic plot. Confronted with a series of unconnected biographical vignettes instead of a continuous narrative, the readers/listeners are no longer able to tell what the war is about or even, in most cases, which side a dead man was fighting on. This omission sets Memorial apart as an act of commemoration, calling into question its very status as a war memorial, because it erases the boundary on which any war is based, the boundary between friend and foe. Recently for the first time, a public monument was erected that entails a similar act of posthumous reconciliation. L’Anneau de la Mémoire, which was unveiled in 2014 near one of the WW1 cemeteries in the Somme department of France, provides an alphabetical tally of the names of the 579,606 soldiers from both sides of the conflict that lost their lives in this region without any reference to their nationality. They are carved on an enormous ellipse, placed precariously on sloped ground as if to show that the peaceful unity between the countries formerly at war, which it took so long to achieve, could break apart again in a moment.

Image 5: L’Anneau de la Mémoire: Names of casualties without any indication of nationality

© Carolin Hahnemann

At the end of his famous poem “The Young Dead Soldiers” Archibald MacLeish has the dead tell this to posterity: “We leave you our deaths. Give them their meaning. / We were young, they say. We have died. Remember us” (9-10). Amid the current memorial boom in western countries, including the United States, Germany, France, and the United Kingdom, Oswald’s Memorial and L’Anneau de la Mémoire stand out as examples of a radically new way of remembering the casualties of war. Whether they can also help us to find new ways of giving meaning to their deaths remains to be seen.

Kenyon College

Gambier, Ohio

Works Cited

Please note that in order to avoid repetition, items that are included in the Appendix have been omitted from the Works Cited list.

Armitage, Simon. “Like, Elizabeth Bishop.” Audio blog post. Poetry with Simon Armitage. University of Oxford: Podcasts, 20 Mar. 2018. <www.podcasts.ox.ac.uk/elizabeth-bishop>.

Auden, W. H. ”The Shield of Achilles.” Collected Poems. Ed. by Edward Mendelson. London: Faber and Faber, 1991. 596-98.

Eco, Umberto. The Infinity of Lists: An Illustrated Essay. Trans. Alastair McEwen. New York: Rizzoli, 2009.

Homer. The Iliad. Trans. Richmond Lattimore. Chicago: Chicago UP, 1951.

Maack, Annegret. “Analogy and Contiguity: A. S. Byatt’s The Biographer’s Tale.” Connotations 13.3 (2003): 276-88. <www.connotations.de/article/annegret-maack-analogy-and-contiguity-a-s-byatts-the-biographers-tale>.

MacLeish, Archibald. “The Young Dead Soldiers.” New & Collected Poems, 1971-196. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1976. 381-82.

Strasburger, Gisela. Die kleinen Kämpfer der Ilias. Diss. Johann Wolfgang Goethe-Universität, Frankfurt am Main, 1954.

Oswald, Alice. Memorial: A Version of Homer’s Iliad. New York: Norton & Co., 2012.

Appendix

Memorial in the News Media and Scholarship

Boland, Eavan. “Afterword.” Memorial: A Version of Homer’s Iliad. By Alice Oswald. New York: W. W. Norton & Co., 2012. 83-90. [Essay]

Burrow, Colin. “The Empty Bath.” The London Review of Books 18 June 2015: 5-8. [Book review]

Burrow, Colin. “On Alice Oswald.” The London Review of Books 22 Sept. 2016: 15. [Book review]

Carroll, Christopher. “The Unbearable Truth of War.” New York Review of Books 29 Mar. 2012. [Book review]

Cheuse, Alan. “A Wintry Mix: Alan Cheuse Selects the Season’s Best.” All Things Considered. National Public Radio. 29 Nov. 2012. [Radio announcement]

Cole, Teju. “All the Names: Alice Oswald’s Memorial.” Brick 90 (2013): 14-16. [Book review]

Cox, Fiona. “Interview with Alice Oswald.” Practitioners’ Voices in Classical Reception Studies 4 (2013). <www.open.ac.uk/arts/research/pvcrs/2013/oswald> [Interview]

Crown, Sarah. “Alice Oswald: Haunted by Homer.” The Guardian 9 Oct. 2011. [Interview]

Farrier, David. “‘Like a Stone’: Ecology, Enargeia, and Ethical Time in Alice Oswald’s Memorial.” Environmental Humanities 4.1 (2014): 1-18. [Journal article]

Green, Peter. “Homer Now.” The New Republic 7 June 2012. [Book review]

Grozdanik, Ena. “Review: Memorial.” Brink Productions, Adelaide Festival, Dunstan Playhouse. The Adelaide Review 5 Mar. 2018. [Theater review]

Guriel, Jason. “Rosy-fingered Yawn.” PN Review 207 (Sept.-Oct. 2012). <www.pnreview.co.uk/cgi-bin/scribe?item_id=8633;hilite=guriel> [Book review]

Hahnemann, Carolin. “Book of Paper, Book of Stone. An Exploration of Alice Oswald’s Memorial.” Arion 22.1 (2014): 1-32. [Journal article]

Hahnemann, Carolin. “Feminist at Second Glance? Alice Oswald’s Memorial as a Response to Homer’s Iliad.” Homer’s Daughters: Women’s Responses to Homer 1914-2014. Ed. Fiona Cox and Elena Theodorakopoulos. Oxford: OUP, forthcoming 2019. [Book chapter]

Harris, Semela. “Memorial.” Productions, Adelaide Festival, Dunstan Playhouse. The Barefoot Review 7 Mar. 2018. [Theater review]

Harrop, Stephe. “Speech, Silence and Epic Performance: Alice Oswald’s Memorial.” New Voices in Classical Reception Studies 8 (2013): 79-91. [Journal article]

Holloway, Amanda. “Memorial Review at Barbican Theatre, London—‘transcendent theatre.’” Brink Productions, Barbican Theatre, London. The Stage 28 Sept. 2018. [Theatre review]

Jaffa, Naomi. “A Conversation with Alice Oswald.” Brick 90 (2013): 17-20. [Interview]

Kahane, Ahuvia. “Modernity and the Twilight of the Epic Gods: Derek Walcott and Alice Oswald.” The Gods of Greek Hexameter Poetry: From the Archaic Age to Late Antiquity and Beyond. Ed. James J. Clauss, Martine Cuypers and Ahuvia Kahane. Stuttgart: Franz Steiner, 2016. 385-406. [Book chapter]

Kellaway, Kate. “Memorial by Alice Oswald.” The Observer 2 Oct. 2011. [Book review]

Linne, Lena and Burkhard Niederhoff. “‘[M]emories and similes laid said by side’: The Paratactic Poetics of Alice Oswald’s Memorial.” Connotations 27 (2018): 19-47. <www.connotations.de/article/lena-linne-and-burkhard-niederhoff-the-paratactic-poetics-of-alice-oswalds-memorial>. [Journal article]

Lista, Michael. “Michael Lista, On Poetry: The Iliad Laid Bare.” The National Post 30 Dec. 2011. [Book review]

Logan, William. “Plains of Blood: Memorial, Alice Oswald’s Version of the Iliad.” New York Times 23 Dec. 2012. [Book review]

Minchin, Elizabeth. “‘Translation’ and Excavation: Alice Oswald’s Excavation of the Iliad.” Classical Receptions Journal 7.2 (2015): 202-22. [Journal article]

Oswald, Alice. “The Unbearable Brightness of Speaking.” The New Statesman 17 Oct. 2011. [Magazine column]

Pache, Corinne. “A Word from Another World: Mourning and Similes in Homeric Epic and Alice Oswald’s Memorial.” Classical Receptions Journal 10.2 (2018): 170-90. [Journal article]

Parke, Phoebe. “Alice Oswald wins 2013 Warwick Prize for Memorial.” The Telegraph 25 Sept. 2013. [News item]

Paul, Georgina. “From Epic to Lyric: Alice Oswald’s and Barbara Köhler’s Refigurings of Homeric Epic.” Epic Performances: From the Middle Ages into the Twenty-First Century. Ed. Fiona Macintosh and Justine McConnell. Oxford: OUP, 2018. 133-48. [Book chapter]

Paul, Georgina. “Excavations in Homer: Speculative Archaeologies in Alice Oswald’s and Barbara Köhler’s Responses to the Iliad and the Odyssey.” Homer’s Daughters: Women’s Responses to Homer 1914-2014. Ed. Fiona Cox and Elena Theodorakopoulos. Oxford: OUP, forthcoming 2019. [Book chapter]

Payne, Tom. “Not for Love.” Times Literary Supplement 23 Dec. 2011. [Book review]

Pestell, Ben. “Poetic Re-Enchantment in an Age of Crisis: Mortal and Divine Worlds in the Poetry of Alice Oswald.” Myths in Crisis: The Crisis of Myth. Ed. José Manuel Losada and Antonella Lipscomb. Newcastle Upon Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2015. 213-21. [Book chapter]

Porter, Max. “Interview with Alice Oswald.” The White Review Aug. 2014. [Interview]

Rosenthal, Mira. “Alice Oswald’s Memorial and the Reinvention of Translation.” The Kenyon Review Online Fall 2013. <www.kenyonreview.org/kr-online-issue/2013-fall/selections/memorial-by-alice-oswald-738439> [Book review]

Schein, Seth. “‘War, What is it Good For?’ in Homer’s Iliad and Four Receptions.” Homeric Epic and Its Reception. Oxford: OUP 2016. 149-71. [Book chapter]

Westwood, Matthew. “Alice Oswald’s Memorial: Pity of War Distilled in a Reimagined Epic.” The Australian 26 Feb. 2018. [Theater review]

“Winged Words.” The Economist 15 Oct. 2011. [Book review]

Womack, Philip. “Memorial by Alice Oswald.” The Telegraph 28 Oct. 2011. [Book review]

Womack, Philip. “Alice Oswald at the Southbank Centre.” Alice Oswald, London. The Telegraph 9 Feb. 2012. [Theater review]

Wood, James. “The Year in Reading: Teju Cole, Alice Oswald, Kierkegaard.” The New Yorker 16 Dec. 2011. [Book review]