Herbert and Gerson Reconsidered: Mystical Music and the Conciliarist Strain of Natural Law in “Providence”1

Angela Balla

Published in Connotations Vol. 33 (2024)

Abstract

Recent scholarship has linked George Herbert to medieval French theologian Jean Gerson, an early theorist of individual natural rights and conciliarism. This essay proposes that Herbert knew Gerson’s ideas on divine and natural law in De Vita Spirituali Animae (1402) well enough to employ them in “Providence.” In this didactic poem, Herbert explains (through his sole use of italics) how divine and natural law work providentially. Pivotal for Herbert is Gerson’s redefinition of the concept of subjective right as a power or faculty intrinsic to an individual, whether human or non-human, since that redefinition underpins Gerson’s conciliarism. Herbert not only uses Gerson’s concept of subjective right at the outset of “Providence,” where the speaker relishes the “right” (4) to “write” (2) as God’s “Secretarie” (8), but Herbert also relies on Gerson’s notion of subjective right throughout the poem. Because Herbert thinks that non-humans have Gersonian subjective rights, he places these creatures within the scope of God’s “permission” (33), a jurisdiction traditionally reserved for rational beings free to act morally (or immorally). Herbert’s choice has immense philosophical and theological consequences, for, according to his Gersonian logic, non-humans serve God, humanity, and each other when they use their powers and faculties to obey God’s objective right, His “command” (33). Their behavior allows them to offer what amounts to moral witness indirectly. Significantly for Herbert, Gerson suggests that when creation exercises their subjective rights in obedience to God’s objective right, their obedience creates a cosmic concord, a mystical music. That concord bolsters Gerson’s conviction that a council of priests may hold a pope accountable. Herbert provocatively metaphorizes Gerson’s logic in “Providence” by depicting a council of creatures headed by “Man” (6) as the “worlds high Priest” (13), who learns to attune himself to the universal harmony in loving obedience to a self-sacrificing God.

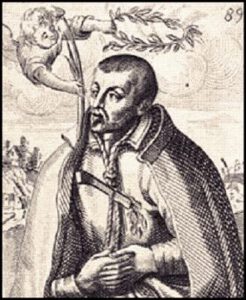

[→ 286] More than any other seventeenth-century poet, Herbert wears his learning lightly, in service of a spiritual humility conducive to true devotion. As the speaker of “The Pearl. Matth. 13” declares, “I know the wayes of learning; both the head / And pipes that feed the presse, and make it runne; / […] / Yet I love thee” (ll. 1-2, 10).2 The contrast between the mind and the heart seems stark, for the speaker announces his preference for loving God over seeking scholarly renown.3 But sometimes in Herbert’s writing what appears to be a firm rejection of academic controversies is actually a deft rejoinder to them, such that there is less professional distance between Bemerton and Cambridge than sometimes supposed.4 Consequently, the task of discerning Herbert’s intellectual debts in his poetry and prose—as well as the ways he makes good on those debts—continues to challenge and to surprise readers. Recently, Christopher Hodgkins has illumined a new context for thinking about Herbert’s “lovers’ quarrel” (“‘Yet I love thee’” 23) with learning by attending to Herbert’s “fleeting mention” of medieval French theologian Jean Gerson (1363-1429) in The Countrey Parson, where Herbert briefly refers to Gerson as “a spirituall man” whose charitably moderate approach to dietary ethics deserves praise (“‘Gerson, a Spirituall Man’” 119). According to Hodgkins, Herbert’s reference to Gerson “suggests Herbert’s greater debts to this man who once led the University of Paris” (“‘Gerson, a Spirituall Man’” 119), debts that Hodgkins does not identify due to his focus on providing a “brief comparative glimpse” (“‘Gerson, a Spirituall Man’” 135) of the two men in order to facilitate a study of their interest in “diet and […] devotion” (“‘Gerson, a Spirituall Man’” 131). I agree with Hodgkins that Herbert’s favorable characterization of Gerson suggests that he may have exerted a “greater” influence on Herbert, especially since Yelena Mazour-Matusevich has recently shown how extensive was Gerson’s reception in the early modern period, in England as well as in Europe.5 I propose that one place worth investigating as a site of that greater influence is Herbert’s didactic poem “Providence,” for that poem’s wordplay, logic, [→ 287] and imagery suggests Herbert’s awareness of Gerson’s work on natural law and mystical theology.6

As I argue in this essay, Herbert’s lyric meditation on God’s immediate and mediate guidance in His creatures’ lives as they obey natural law hints at Herbert’s familiarity with Gerson’s ideas, particularly those in De Vita Spirituali Animae (1402). First, Herbert appears conversant with Gerson’s notion of a created order based on caritas and buttressed by the concord between divine and natural laws, a concord that produces a mystical music within the cosmos, that awesome temple. For those who question Gerson’s influence on this matter since earlier philosophers, notably Boethius, also believed in a musical cosmos, Boethius’ mechanical notion of musica mundana differs from Gerson’s allegorical understanding of the canticum divinale. Whereas Boethius thought that the musica mundana literally activates the musica spiritualis, Gerson imagined that divine music figuratively results from God’s creatures knowing and loving Him.7 Gerson’s mystical sense better suits Herbert’s depiction of God as a loving Composer desiring His creatures to accord with Him in love. Second, Herbert appears to share Gerson’s Thomist view that human nature excels non-human nature given humanity’s access to right reason, a divine faculty that for Gerson obligates a church council to hold papal authority in check. Herbert plausibly draws on these Gersonian ideas—a mystical music perceptible by the soul and a conciliarism based on right reason—throughout “Providence,” poetically shifting theological and philosophical hands. Over the course of the poem, one of the longest in The Temple, Herbert shows how the sweet concord of non-human nature following divine law rebukes humanity’s pride. By figuring non-human nature as a harmonious proto-church council that reminds “Man” (6) of his duty as “the worlds high Priest” (13) and alerts him to gross abuses of office, Herbert may even nod to Gerson in a witty conciliarist move.8 Additionally, as Herbert shows how the providentially beautiful harmony of non-human nature reveals the often-hubristic division between humans and non-humans created by Man’s fallen reason, he appears to [→ 288] agree with Gerson that such harmony stirs a longing for a mystical connection with all creatures that poetry may foster.9 Investigating the possibility that Herbert reworked some of Gerson’s ideas in “Providence” allows readers to see that Herbert remained engaged with academic debates while at Bemerton. If Herbert did borrow from Gerson, as I contend is likely, his light touch in bringing scholarly concerns to bear on pastoral care testifies to his humble refusal to lord his learning over his flock, and the surprising reach of medieval disputes.10

1. Providence and the Right to Write: Herbert’s Gersonian Approach to Natural Law

One of the most striking aspects of the opening stanza of Herbert’s lyric “Providence” is its buoyant joy, especially since early modern accounts of providence regularly concentrated on shocking events and sobering signs, each with eternal portent. Herbert’s marked departure from his contemporaries in depicting Providence likely owes something to Gerson, but to see how and why, it is necessary briefly to survey those contemporaries’ work. According to Alexandra Walsham, “‘Strange and wonderful newes’ of terrible disasters, sudden accidents, and bizarre prodigies was a major theme of the blackletter broadside ballads and catchpenny quarto and octavo pamphlets which flowed from city publishers in growing profusion between 1560 and 1640,” an output that “penetrated the provinces and countryside” (33). While popular sources offered a shocking providentialism, ecclesiastical texts gave a sobering one, urging the laity to discern God’s hand in quotidian events. Walsham records that “English Protestant divines discussed the doctrine [of providence] in exhaustive detail and with wearisome frequency; it was a prominent theme of sixteenth- and seventeenth-century academic theology and practical divinity” (9) as well as sermons. Whereas some clergy urged their parishioners to view “[e]very happening, catastrophic or trivial,” as “a signpost concerning the Lord’s soteriological intentions” (15), other writers viewed events through the lens of vestigial paganism, as when they assigned responsibility to fate, [→ 289] chance, the deities Fortuna or Nature, elves, hobgoblins, or witches (Walsham 20-31).11 Absent from Walsham’s description of these texts is a sense of joyful freedom in them, whether of God in His sustenance of Creation or of humanity in their response to God’s activity. Yet that joyful freedom bursts from the speaker of “Providence” as he contemplates God’s creation:

O sacred Providence, who from end to end

Strongly and sweetly movest! shall I write,

And not of thee, through whom my fingers bend

To hold my quill? shall they not do thee right? (1-4)

What prompts the speaker’s joy is not simply that Providence “strongly” moves; it is also that He moves “sweetly.” Helen Wilcox notes that “sweet” (in any of its variants) is “One of H.’s favourite words,” for it signals “his intense experience of God,” which ranges from “sensual pleasure and artistic beauty to moral virtuousness and redemptive love” (xliv). Pivotal to Herbert’s intense experience of God is the freedom to respond to Him, and Herbert alerts readers to that freedom when his speaker asks two questions: shall he write of God? And if he does, shall his fingers write rightly? The rapturous awe of the speaker’s opening exclamation suggests ideal answers to these questions, but the fact that they go unanswered signals the importance of his choices. In just several lines, Herbert’s emphasis on joyful freedom as the start of a proper response to “sacred Providence” makes a significant contribution to early modern providentialist discourse.12

Herbert’s recalibration of the emotional and spiritual tenor of this discourse owes much to scripture and the liturgical tradition, but these sources do not clearly explain the hopeful eagerness surrounding the speaker’s writing ability, while Gerson’s theological and philosophical work may. Herbert’s primary debt in this stanza is to the apocryphal Book of Wisdom: “Wisdom reacheth from one end to another mightily: and sweetly doth she order all things” (8:1).13 Close behind scripture in terms of influence is the ancient O Antiphon addressed to Sapientia: “O Wisdom, coming forth from the mouth of the Most High, / reaching [→ 290] from one end to the other mightily, / and sweetly ordering all things” (1-3).14 Both sources exhibit some of the buoyant joy that animates Herbert’s opening stanza in marked contrast to other providentialist writings. A third source, Jean Gerson’s De Vita Spirituali Animae, while less recognizable to many readers, appears to undergird the logic of the speaker’s questions, helping to bolster their enthusiasm. Gerson’s treatise, a collection of six lectures on natural law and mystical theology, offers an influential understanding of the distinction between objective and subjective right, two components of the mystical music that Gerson believes resonates throughout the universe given the concord between divine and natural laws. His distinction between objective and subjective right plausibly informs Herbert’s rhyme of “write” with “right.” The sense of the rhyme is that the speaker ought to feel an imperative to write fairly of God, to inscribe just and beautiful claims about Him. Still, the only way that imperative works is if he has the ability to write. Herbert’s play on the objective obligation to act morally and the subjective capacity to do so recalls Gerson’s definitions of objective and subjective right. In his second Lectio, Gerson denotes objective right as God’s law (lex), “a true sign revealed to a rational creature” via “divine right reason willing that creature to be obliged either to do or not to do something conducive to his sanctification so that he may attain eternal life and avoid damnation.”15 By contrast, Gerson denotes subjective right (ius) as “an immediate faculty or power belonging to someone according to the dictate of right reason.”16 Whereas objective right concerns rational creatures’ duty to obey God’s moral commands as revealed in divine and natural law, subjective right involves creatures’ innate capacity to do what God decrees.17 These definitions clarify Herbert’s “write”/“right” rhyme. Marveling at how God’s divine and natural laws “Strongly and sweetly movest […]” the universe “from end to end,” the speaker feels a moral need to respond in kind to God as Legislator, and so asks, “shall I write”? Then he wonders whether his writing will suffice, asking whether his fingers will “do thee right,” thereby indicating the possibility that he has the mental, physical, and [→ 291] spiritual abilities to write well of God. That he prefaces these questions with “not” signals his trust in the implied positive answers.

Gerson’s distinction between objective and subjective right may inform Herbert’s rhyme further if one consults the Latin text. To the extent that Gerson’s notion of objective right imbues Herbert’s word “write,” there is connotative play between God’s lex and Herbert’s lexicon. And to the extent that Gerson’s notion of subjective right inhabits Herbert’s word “right,” there is connotative play between ius as a power or faculty and iustum as the right or just end. If Herbert had in mind such Latin wordplay, the fact that it registers at one remove, only through a mental pun, suggests his decorous restraint, but that fact may also suggest his hope in a providential order to language.18 At a minimum, the exuberant tone of his ancient sources, combined with the liberating logic of De Vita Spirituali Animae, help to explain the joyful freedom of Herbert’s opening stanza.19 Even so, for readers skeptical about even a denotative connection between Herbert’s rhyme and Gerson’s definitions of objective and subjective right, perhaps because those definitions seem commonplace and thus unattributable to Gerson alone, it is important to remember that they were innovative in Gerson’s day and influential in Herbert’s as Gerson’s legacy grew.20 For readers inclined to doubt that Gerson’s influence extends past Herbert’s first stanza, it is worth asking what Herbert read that so engaged him with medieval natural law theory that he explicates some of that theory partway through “Providence” in his only use of italics in the poem. Perhaps mindful of how Donne often borrows from medieval philosophical and theological debates in his profane and sacred verse, Herbert delves into established categories of divine and natural law, keen to illuminate how these categories work together to demonstrate the wisdom of Providence.21 As he does so, he deftly changes hands, moving from theology in the first stanza to philosophy in the second stanza:

We all acknowledge both thy power and love

To be exact; transcendent, and divine;

Who dost so strongly and so sweetly move,

While all things have their will, yet none but thine.

For either thy command, or thy permission [→ 292]

Lay hands on all: they are thy right and left.

The first puts on with speed and expedition;

The other curbs sinnes stealing pace and theft. (29-36)

In the first of these stanzas, the speaker intriguingly recognizes God’s “power and love” as the cosmos’ driving forces. But this unusual pairing gets dwarfed by more surprising details, like the speaker’s pronoun shift from the first-person singular to the first-person plural (a point to which I will return), and the way he underscores the poem’s initial claim that Providence “strongly and sweetly” moves. Then, an even more surprising detail arrives: when, in the second of these stanzas, the speaker explains his thinking in the first, he not only uses terms familiar from medieval natural law theory, but also he italicizes these terms, making them impossible to ignore. Within that theory, God’s “command” refers to His preceptive will, what God orders His creatures to do (or not to do), while God’s “permission” refers to his permissive will, what He allows His creatures to do (or not to do). While it is possible to distinguish between three types of natural law—the preceptive, the prohibitive, and the permissive—Herbert clearly groups the first two types within God’s commands, leaving the last type to fall within God’s permissions. In doing so, he may be following Gerson’s example, for Gerson also includes prohibitive divine law within preceptive divine law when he declares, “The divine preceptive law is a true sign revealed to a rational creature that is a notice of divine right reason aiming to hold or bind that creature to act or not to act so as to sanctify it, that it may achieve eternal life and avoid damnation.”22 Whether Herbert is following Gerson or agreeing with him unawares becomes easier to see if readers situate Herbert’s two stanzas in the context of the medieval debates on divine and natural law that Herbert signals his knowledge of through his arresting use of italics.

Within this context, the speaker’s earlier, easily overlooked assertion that God’s “power and love” move the cosmos appears increasingly strange. To those working under the influence of Thomas Aquinas, whose Summa Theologiae systematized pagan and Christian ideas about divine and natural law, what drives the cosmos are God’s right reason and will.23 Whereas Thomists prioritized God’s right reason above His [→ 293] will in their efforts to grasp His moral power, voluntarists like William of Ockham prioritized God’s will above His right reason.24 The first person to balance God’s will and right reason in order to comprehend His moral power better was Pierre d’Ailly, but neither he nor his predecessors paired God’s power with His love, as Herbert does.25 Herbert’s scholarly and clerical training equipped him to think independently on the subject of divine and natural law, but it still makes sense to ask what he could have read that helped to inspire the theological and philosophical initiative he shows in stressing God’s love alongside His power.

Given my attempts thus far to prove the probability that Gerson’s thinking shaped Herbert’s in “Providence,” it should come as no surprise that I posit De Vita Spirituali Animae as a likely source for Herbert’s daring in averring that God’s “power and love” motivate the universe as it operates providentially according to His preceptive and permissive laws. In Gerson’s treatise, God’s love grounds the universe, and His power, expressed as His will and right reason, work equally out of that love. Because Gerson aims at pastoral care rather than natural philosophy, Gerson spends more time discussing rational being than non-rational being, which makes sense in light of his title, On the Spiritual Life of the Soul. Still, his scholastic exploration of human nature, coupled with his periodic mentions of non-human nature, allow readers to see how Herbert may have relied on some of Gerson’s thought in “Providence.” In his fifth Lectio, Gerson refers to the “harmony of the spiritual life which is charity.”26 He then clarifies that the “principle harmony of the soul, in which consists the soul’s true life […] is God.”27 To Gerson, the fact that God’s love is the ground of the soul’s being implies that God’s love is the source of all being, which in turn suggests that God’s Being is love, a logic that has scriptural support since John of Patmos twice avers, “God is loue” (Holy Bible: 1611 Edition, 1 John 4:8, 1 John 4:16). Regarding God’s power, Gerson states that “nothing happens without God causing it, and nothing is true without the first truth, for all wisdom is from the Lord God.”28 Although here Gerson does not refer directly to God’s will and right reason, he seems to do so indirectly in his references to “first cause” and “first truth.” Later, he not only [→ 294] refers to God’s will and right reason directly, but also he claims that they are equally balanced: “in moral practices, right reason is not prior to the will” because “neither is prior to the other in God.”29 Gerson’s conviction that God’s love founds a cosmos within which His power works equally through His will and right reason so as to make his His laws known resembles Herbert’s thinking about Providence in the two stanzas above. Both men agree on the loving basis of the universe, and they agree that God expresses His power through an equal balance between His will and right reason. Moreover, both men agree that humans may perceive God’s loving power through a rational grasp of the objective right of preceptive law and the subjective right of permissive law.

Yet Herbert’s readers may well wonder about what non-humans perceive of God’s loving power, especially if those readers look closely at the speaker’s explication of divine and natural law in the two stanzas quoted above. Since the niceties of natural law theory may not appeal to all readers, it may be tempting to breeze through these stanzas, assuming that God’s command and permission applies to humans, while God’s command only applies to non-humans. On this view, only humans have fully free will, so only they need permissive natural law, and non-humans do not sin, so they do not need permissive law to curb sin. But the speaker proclaims that “either” God’s command “or” His permission “lays hands on all,” implying that humans and non-humans fall under the scope of God’s command and permission. Provocatively, Herbert suggests that non-humans, in addition to obeying God’s command, enjoy something like a liberty covered by God’s permission.30 The only way that this shocking suggestion makes sense in the context of divine and natural law, a context that Herbert begs his readers to notice through his use of italics, is if Herbert relies on Gerson’s famous definition of subjective right cited above, wherein that right (ius) is “an immediate faculty or power belonging to someone according to the dictate of right reason.” This definition alone allows non-humans to come within the jurisdiction of God’s permissive law. [→ 295]

For those who still doubt the applicability to Herbert of Gerson’s thinking on this point because they assume that Herbert’s poem does not suggest that non-humans share in right reason, it is important to point out that because Gerson believes that “right reason and its dictates are firstly, originally, and essentially in God,” he views right reason as a participative faculty that humans access through their connection to God.31 To use an anachronistic but helpful analogy, right reason resides in God somewhat like a software program stored in the cloud runs only on devices with authorized access. Thus, to Gerson, non-humans have subjective rights according to right reason located not in themselves but in God. So, while non-humans do not participate or share in God’s right reason as humans do, non-humans still function according to God’s right reason. As they exercise their abilities according to His wisdom, they experience His permission to be themselves, to do whatever is theirs to do within the scope of His will. That Gersonian understanding appears in “Providence.” As Diana Benet sums up the speaker’s logic in stanza eight, “God’s will is that all things should have their will,” but she does not identify the root of the speaker’s claim that “all things have their will, yet none but thine” (161). That root plausibly is Gerson, who declares in a memorable passage, “every positive being has as much of its existence and the consequence of its goodness as it has of [subjective] right […] In this way the sky has a right to rain, the sun to shine, the fire to heat, yes, and every creature in all that it is able to do well by its natural ability.”32 This idea, which lays the foundation for a modern notion of subjective rights, surely informs Herbert’s choice to include non-humans within the scope of God’s permissive will.

Because Herbert appears indebted to Gerson in these two stanzas, whose natural law theory informs the entire poem, it is crucial to mention one more consequence of their logic. Herbert suggests that, as non-humans exercise their subjective right to do whatever they have the power or faculty to do in a situation, they offer—with some degree of freedom, some measure of God’s permission—what amounts to moral witness indirectly, thereby helping humans to curb sin. Although he [→ 296] surely agrees with Gerson that non-humans are not free in the way that humans are since non-humans lack the divine faculty of right reason, Herbert nevertheless goes beyond Gerson in clearly recognizing non-humans’ ability to obey God’s permissive law. Irwin observes that, in various writings, Gerson hesitates to declare definitively that the actions of non-humans exhibit a kind of liberty, even as he ascribes to their actions a moral value worthy of praise.33 For him, the laudable aspects of non-human behavior appear as these creatures conform to natural law, and through it divine law, since “all the principles of natural law are properly said to be of divine law, though in a different manner.”34 Herbert undoubtedly would concur that natural law falls within the purview of divine law, such that as non-humans follow natural law, they necessarily obey some divine law. His poem accordingly suggests that even as all power is God’s power, God is just in His use of that power: He directs it in and through concordant laws.35 In the parts of “Providence” that surrounds these two stanzas, Herbert plausibly uses Gerson’s natural law thinking at least as a partial basis for his own, showing how non-human nature accords with God’s decrees in ways that inspire and correct human nature. The creatures thus offer something like a moral testimony, even a mystically musical one. As Herbert’s speaker finds his ordained part in the harmony produced by Creation and joins in the “musick” (40) that God orchestrates, he models an ethic of engagement with the natural world, both human and non-human. Writing well, virtuously and beautifully, facilitates his moral and spiritual participation in the world around him, and demonstrates that truly good poetry exhibits the strength and sweetness of Providence. Herbert thus reveals how poetry and its writers may reflect the wonderfully lyrical nature of God.

2. “What musick…!”: Poetic Praise as Providential Accord

Near the outset of “Providence,” however, the speaker appears further from this last goal than the opening stanza suggests he hopes, and some readers realize.36 In just the second stanza, the speaker revels so much in his subjective right to write that he mixes fitting pride with blind [→ 297] hubris, displaying a fallen anthropocentrism that corrupts the speaker’s joy with smugness, subtly at first, and then not so subtly. But as he considers his place in the natural order, and specifically as he meditates on non-human creatures in relation to himself, he gradually becomes more right-sized, less grandiose, more capable of genuine service to God and other creatures. Although the speaker initially sees his service more literally, according to the letter of the natural law, once he performs that service, he understands it more metaphorically, according to the spirit of that law. As I contend in this section, Herbert’s poetic dramatization of his speaker’s humbling—a process that recurs throughout the poem—appears indebted not only to Gerson’s notions of objective and subjective right, but also and especially to Gerson’s sense that creatures’ conformities to natural law, and thus their obedience to divine law, creates a cosmic harmony. That harmony is no Boethian mechanical marvel, but a mystical music based on God’s self-sacrificing love. Furthermore, to keep his speaker humble, Herbert creatively applies Gerson’s ideas about mystical theology so as to depict a speaker using Gerson’s affective meditational tools to develop his devotion. Ultimately, in both the part of the poem that precedes the two stanzas quoted above and the part of the poem that follows them, Herbert shows his speaker learning to use his intellectual and emotional faculties with a glorious humility proper to them. But for the speaker to praise God rightly, using words that only he has, he must first learn how other creatures praise God, and become attuned to Providence working in and through them.

The most significant lesson in the speaker’s need for humility starts early in “Providence.” In the poem’s second stanza, the speaker highlights humanity’s rational capacity (their subjective right) to know God’s law (the objective right), proclaiming, “Of all the creatures both in sea and land / Onely to Man thou has made known thy wayes” (5-6). Wondering at Man’s greatness in a way that recalls Psalm 8:4, “What is man, that thou art mindfull of him?” the speaker effectively answers the psalmist’s question, but with a note of presumption absent from the psalmist’s answer.37 To be fair, “Onely” humanity participates in divine [→ 298] right reason, which is why their obedience to God’s will through their use of His right reason enables them to worship God through language, and written language at that. Mindful of these matters, the speaker stresses Man’s vocation to write, for God “put the penne alone into his [Man’s] hand, / And made him Secretarie of thy praise” (7-8). Because Man’s signature talent is his linguistic ability, “versing” (39) is one of his crowning achievements, a feat exclusive to him.38 But those who do not write poetry in praise of God are still equipped to be His secret-keeper, clerk, correspondent, and minister.39 These human capabilities are all worth celebrating, and the speaker does so rightly. Indeed, the length and complexity of “Providence” shows Herbert relishing his own ability to write poetry. The problem with the speaker’s exultation is that his use of the word “Onely” is dangerous: he allows the truth he knows to become tainted by “proud exclusivity” (Guibbory 81).40

While the speaker’s claim that Man alone may compose God’s praise is, of course, literally true, his claim is spiritually false, as scripture that Herbert knew well evinces. Take Job, for example, who averred: “But aske now the beasts, and they shall teach thee; and the foules of the aire, and they shall tell thee. Or speake to the earth, and it shall teach thee; and the fishes of the sea shall declare vnto thee. Who knoweth not in all these, that the hand of the LORD hath wrought this?” (Job 12:7-9). Beyond Job, there is Jesus, who replied to the Pharisees, “I tell you, that if these [disciples] should holde their peace, the stones would immediatly cry out” (Luke 19:40). Then there is John of Patmos, who recorded in his prophetic vision, “euery creature which is in heauen, and on the earth, and vnder the earth, and such as are in the sea, and all that are in them, heard I, saying, Blessing, honour, glory, and power bee vnto him that sitteth vpon the Throne, and vnto the Lambe for euer and euer” (Rev. 5:13). These instances of non-human creatures testifying to spiritual truths are hardly exhaustive.41 Both in number and fame, they suggest that Herbert disagrees with the discordant note of unhealthy pride heard in the speaker’ assertion that “Onely” Man worshipfully records God’s secrets. In stanzas three through five, Herbert increases the volume of that off-key note until it is hard for the speaker to miss. [→ 299]

By the third stanza, the speaker’s tone has veered noticeably from the buoyant joy of the first stanza and the proud confidence of the second stanza; now, the speaker sounds sharply condescending. “Beasts fain would sing; birds dittie to their notes; / Trees would be tuning on their native lute / To thy renown” (9-11), the speaker fantasizes, recreating other creatures in Man’s image, as if somehow God failed to make non-human creatures sufficient in themselves for the purposes He set for them. Yet because non-human creatures cannot fulfill human standards, he ends his fantasy by pitying their pathetic state: “but all their hands and throats / Are brought to Man, while they are lame and mute” (11-12). Part of what interferes with the speaker’s right understanding and feeling about human and non-human creatures is his literalism, his hyperfocus on what is materially evident, whether about the animal, vegetable, and mineral bodies that he perceives through his senses, or about his own body, with its various powers and faculties. Earlier in the poem, precisely these abilities were the source of his justified rejoicing, but now, his limited perspective yields a distorted image.

Still, Herbert paints a more complicated picture of the speaker’s human nature than just intellectual and emotional corruption, which is why the speaker’s anthropocentrism registers in a more nuanced way in stanza four. The speaker valorizes humanity in a way that seems to have biblical support when he declares arrestingly that “Man is the worlds high Priest” (13). Placing Man in a vocation with Jewish, Orthodox, Roman Catholic, and Protestant expressions, the speaker strikingly includes non-human nature as part of the fold. He correctly calls Man a priest insofar as scripture describes Peter telling Christ’s followers, “But yee are a chosen generation, a royall Priesthood, an holy nation, a peculiar people, that yee should shewe forth the praises of him, who hath called you out of darkness into his marueillous light” (1 Pet. 2:9). Still, being a member of a royal priesthood is not the same as being the high priest himself. It is thus tempting to wonder whether the speaker has transgressed natural and divine law by forgetting the verse, “wee [Christians] haue a great high Priest, that is passed into the [→ 300] heauens, Iesus the Sonne of God” (Heb. 4:14).42 Skeptical readers may counter that the speaker justly distinguishes Man from Christ by announcing that Man is the world’s high priest, whereas Christ is the world’s and heaven’s high priest. Readers may further contend that it is possible for Man to be a high priest since the Bible makes clear that “euery high Priest taken from among men, is ordeined for men in things pertaining to God” (Heb. 5:1.). The problem with these objections is that for them to work logically, Man, as “the worlds high Priest,” would have to accept that non-humans, at least some of them, qualify to be priests, just not high priests. Yet nothing in Herbert’s poem so far gives any indication that the speaker, the self-appointed spokesperson for Man (as distinct from Herbert), is willing to view non-human creatures, or even some of them, as the world’s priests under Man as their high priest. In fact, in the lines immediately following the speaker’s assertion that Man is “the worlds high Priest” who “doth present / The sacrifice for all” (13-14), the speaker states that “they [non-human creatures] below / Unto the service mutter an assent” (14-15). But, as Herbert knew, there is no muttering in scriptural accounts of non-human creatures proclaiming God’s glory. These creatures confidently proclaim what they know, in whatever sense they know it. Since Christianity underscores the need to satisfy the spirit of the law over its letter, it is a mistake to assume the speaker is always spiritually right when he stresses part of the literal truth. My point is that the speaker’s proud anthropocentrism prevents him from perceiving how non-human creatures testify harmoniously to the wonders of Providence. That limitation is tragic insofar as the logic of his metaphor of Man as “the worlds high Priest” requires that at least some non-humans take on something of a priestly role.

Having elevated Man to such a global height in the fourth stanza, the speaker in stanza five feels an overdeveloped sense of responsibility for offering God’s praise poetically. The speaker’s anthropocentrism burdens him so much that he assumes that Man must supply the verbal worship that non-humans cannot, or else these creatures languish spiritually. According to the speaker, the person who does not worship [→ 301] God linguistically “Doth not refrain unto himself alone, / But robs a thousand who would praise thee fain, / And doth commit a world of sinne in one” (18-20). From one perspective, the speaker’s hubris leads him to imagine that a single refusal to worship God via the spoken or written word is a microcosm of rebellion that commits a macrocosm of sin. His ignorance of scriptural assurance cited above that non-human nature has praised God in the past, is doing so in the present, and will do so in the future means that he misses how non-human nature serves God as differently abled secretaries, even as teachers for those who heed their witness. From another perspective, however, the speaker intimates that in some mystical way, non-human creatures do have a legitimate claim to humanity’s words. If their claim is not exactly a right to human worship, it may at least be a stake in it. On this last view, non-human nature has a measure of spiritual authority and maybe even the means to hold Man accountable for ignoring it. Within the speaker’s complex, conflicted logic, at once problematic and profound, runs a subtle strain of conciliarist thinking that may well owe something to Gerson given his status as a leading conciliarist in his period and afterward.43 Yet to perceive how Herbert develops that strain in later stanzas while recalling other aspects of Gerson’s work, one must first observe how Herbert brings the speaker into providential accord with non-human nature via a concerted lesson in humility.

That humbling process operates quietly while the speaker’s pride persists, as stanzas six and seven show. His arrogant anthropocentrism reaches a high point in stanza six when he imagines that “The beasts say, Eat me” (21), and “The trees say, Pull me” (23). This arresting moment recalls Ben Jonson’s ode to Robert Sidney’s country house, “To Penshurst,” wherein a variety of creatures vie to sacrifice themselves for their lord’s sake. On land, they passively serve their master, for “The painted partridge lies in every field / And for thy mess is willing to be killed” (29-30). In water, by contrast, they serve actively, as when “Fat, agèd carps […] run into thy net” (33). Not to be outdone, amphibians offer themselves up with flattering athleticism: “Bright eels […] emulate them, and leap on land, / Before the fisher, or into his hand” (37- [→ 302] 38). While Jonson depicts non-humans as if they exist largely to please humanity, Herbert exaggerates that attitude by having his speaker smugly put non-humans in their place. For example, the speaker reminds the “beasts” that “The tongue is yours to eat, but mine to praise” (22), and he tells the “trees” that “the hand you stretch, / Is mine to write, as it is yours to raise” (23-24). He thus harps on his earlier point that non-human creatures lack Man’s signature faculty, that Gersonian right to write justly.44 Still, for all the proud anthropocentrism evident in the speaker’s belief about what the beasts and trees “say” to Man, the fact that they speak to him at all is a surprise since only three stanzas earlier, he thought them “lame and mute.” Apparently, his contemplation of non-human creatures, though undertaken with a superior attitude, has humbled him enough to realize that Providence has given non-humans more faculties than he thought.

At this point in stanza six, it is barely possible for the speaker to perceive that non-humans have voices, however figuratively understood, and that non-humans providentially instruct Man, a possibility that he admits when he considers whether “beasts must teach” (21). The speaker’s shift to the second person via the possessive “yours” (22, 24) and “you” (23) so as to address non-human creatures directly further indicates his recognition that he is not as superior as he once thought. Even as he stridently asserts Man’s privileged place in the created order, he starts to temper his assertions, as if the visceral connection he shares with the material world reins in some of his excesses. Consequently, in stanza seven, when he turns again to Providence, he praises that “most sacred Spirit” (25) on behalf of himself and “all my fellows” (26). Contemplating nature enables him to see fellowship where once there was only lordship.45 Admittedly, some vestiges of pride appear in his depiction of Man as a feudal lord paying “rent” (27) to God as Dominus out of the “benefit accrue[d]” (28) from other creatures. While it is true that Man enjoys dominium over these creatures according to scripture, since God told Adam and Eve, “haue dominion ouer the fish of the sea, and ouer the foule of the aire, and ouer euery liuing thing that mooueth vpon the earth” (Gen. 1:28) it nevertheless sounds like [→ 303] Herbert’s speaker lords his privileged place above the creatures he has yet to listen to fully. Still, the pride in his anthropocentrism is tempered by a newfound sense of fellowship with non-human nature because all serve the ultimate King.

With a new, humbled spirit in stanza eight, the speaker shifts pronouns yet again, adopting the first-person plural “We” (29) for the first time as he and his “fellows” confess how Providence works through both “power and love,” moving “strongly and sweetly.” Intriguingly enough, at the moment when the speaker finds fellowship, perhaps even kinship, with non-human creatures simply because he chooses to humble himself, he becomes able to use his subjective right to write rightly, to the point of using italics in stanza nine. Part of what enables him again to write justly, after a lapse of six stanzas, is that he accesses the faculty of right reason, which Man alone of God’s creatures may, to discuss of the most thorny and difficult subjects he can, medieval natural law theory. The fact that he does so in poetry is remarkable. Since I have already discussed stanzas eight and nine in the previous section, there is no need to regurgitate my findings here. But it is worth stating that by reflecting on and writing about the relation between God’s “command” and “permission,” the speaker is paradoxically reduced and enlarged, simultaneously humbled and exalted, all while appearing closer to his rightful spiritual size. Gone (for the moment) are his distorted observations and extreme moods. Instead, he serves his human audience by instructing them in unfamiliar concepts using balanced rhetoric and a calm tone. He also serves his non-human audience by finally having a spirit of respectful temperance toward them. Though there is no creature on earth other than Man who could possibly parse the subtleties of natural law, the speaker does so beautifully, simply, smartly, all without lording it over others. The fact that no commentator that I know of has explored the significance of the speaker’s natural law thinking demonstrates how suavely Herbert utilizes his ample learning here. [→ 304]

Fascinatingly, not only does the speaker find his rightful place amongst all creatures by using his signature human talents in companionate ways, but also he rediscovers the joy he had when the poem opened. The speaker’s realization that “Nothing escapes” (37) God’s preceptive and permissive wills because all are caught up in the legal trajectories of God’s eternal justice leads him to affirm what Man knows only through divine revelation: “all must appeare; / And be dispos’d, and dress’d, and tun’d by thee, / Who sweetly temper’st all” (37-39). The speaker’s vision of Providence as the cosmic Composer is fascinating, particularly given his exuberance in marveling, “If we could heare / Thy skill and art, what musick it would be! (39-40) This music is no conventional music of the spheres, no Boethian cosmic harmony, since the music to which the speaker refers is in some mysterious way moral, and in every way legally just. That is because metaphoric, even allegorical, tuning and tempering are required, which means both that earlier music went awry, and some music at least is now proceeding beautifully.

These ideas, combined with the fact that Herbert has deliberately invited readers to think about natural law in the preceding stanzas, make it hard not to think of De Vita Spirituali Animae, particularly Gerson’s vision of how creaturely being depends on God’s Being in a brilliantly complicated yet ordered way. As mentioned earlier, since Gerson’s treatise aims at pastoral care rather than natural philosophy, his most developed commentary concerns humans instead of non-humans. Nevertheless, his description of how rightly ordered human behavior conforms variously to divine and natural law sheds light on how non-human behavior similarly conforms to that law, though within the ordained limits of the creature. In an admittedly difficult passage, Gerson works hard to articulate all the ways that a human may obey God’s law on just one occasion:

In the same act, multiple rectitudes and goodnesses may coincide: one of nature, another of manners, another of grace, another of glory; and this [coincidence] occurs according to the diverse ways of considering that act to be conformed variously to the divine law or goodness, not that in God there is [→ 305] any diversity in his laws which may be called real or formal, but that we conceive the same divine law in diverse ways and consider it according to really distinct attitudes toward creatures; these attitudes do not exist in God by Himself, but in Himself and the creatures thus related and considered, from which [consideration] distinct concepts are formed by the intellect and abstracted by a power far stronger than [animal instinct].46

According to Gerson, when a rational creature performs a single act, that act conforms to divine law in one or more ways, whether because it heeds the laws of nature, the demands of good custom, the gifts of grace, and/or the rewards of glory. These different kinds of conformity to divine law do not exist in God Himself alone, like right reason does. Instead, differences in conformity to divine law occur in the individual relations between God and His creatures. Gerson hence quite fittingly suggests that the differences in how creatures conform to divine law appear best to rational creatures who contemplate others, human or non-human, since rational creatures are capable of observing such differences. Additionally, he suggests that when rational creatures contemplate others, their contemplative behavior itself conforms to divine law. He thus implies that there is a hierarchy to creatures’ conformity to divine law, one which adds to the spectacular moral dynamism of God’s creation. Admittedly, it is hard to picture that dynamism. One may think, for example, of God’s will for each creature emanating outward toward that creature like a ray of light, which the creature’s own will returns to God in and through its obedience to divine law.47 But it is not hard to imagine that dynamism as a symphony of concordant notes and rhythms. That kind of moral music, whereby all creatures play their instruments—their powers and faculties—according to God’s objective will with a creative liberty allowed by God’s permissive will, fits well with Herbert’s speaker’s exclamation, “If we could heare / Thy skill and art, what musick it would be!”

The humbling process brought about by the speaker’s summation of divine and natural law in the two stanzas cited above prompts him to deepen his understanding of non-human creatures as his “fellows” in the remainder of the poem. His striking label suggests that non-humans [→ 306] are not just instruments of the divine; they are fellow beings, descendants of the One whose Being animates the universe. Because of this spiritually expansive, emotionally generous, and intellectually open view of Creation, the speaker refers to non-humans in human terms, subtly at first and then not so subtly. “Tempests are calm to thee; they know thy hand, / And hold it fast, as children do their fathers, / Which crie and follow” (45-47), the speaker tells God. The speaker uses a simile to elaborate on the earlier “fellows” reference, which distances humans from non-humans on the Great Chain of Being. As the poem continues, however, the speaker opts for metaphor through the use of gendered pronouns for animals, vegetables, and even minerals. For example, he states, “no beast but knows his feed” (50). His imaginative leap is not huge since beasts are generally male or female. But he then avers, “Each creature hath a wisdome for his good” (61), implying that all creatures, whatever their nature, exhibit something recognizably human in their being. Thus he refers to a rose as masculine, for its “cure” (78) signals that the rose is a veritable vegetal doctor. A few lines later, the speaker marvels at how minerals sometimes warn Man, thereby aiming at his good: “when he digs the place, / He makes a grave,” the speaker relates, “as if the thing had sense, / And threatened man, that he should fill the space” (82-84). The key phrase is “as if”; by likening dirt to a human (an unusual move until one remembers the Hebrew word for dirt, “adamah,” which Herbert likely knew), the speaker imagines what that dirt would say to a clueless human, and then the speaker articulates that warning on the dirt’s behalf. Amazingly, the speaker serves as a secretary for gravel.

Indeed, so powerful is his impulse to communicate with a non-human that he turns away from Providence, the primary audience of his prayer, and speaks directly to a mineral. Meditating on the weather, he rehearses what he knows of climate history: “When yet some places could no moisture get, / The windes grew gard’ners, and the clouds good fountains” (115-16). Because of his figuration of wind as a gardener, a counterpart of sorts to humanity, he becomes distressed at the prospect of future storms, and so apostrophizes the “good fountains”: [→ 307]

Rain, do not hurt my flowers; but gently spend

Your hony drops: presse not to smell them here:

When they are ripe, their odour will ascend,

And at your lodging with their thanks appeare. (117-20)

The childlike faith that the rain has sense enough to hear his petition and fellowship enough to heed it is both strong and sweet. For though that faith-filled speaker stands on the border between Christian kinship with Creation and pagan animism, the speaker leans toward Christian kinship. Indeed, he may aim to follow Jesus’ teaching: “verily I say unto you, If yee haue faith as a graine of mustard seed, yee shall say vnto this mountaine; Remove hence to yonder place: and it shall remoue, and nothing shall be vnpossible vnto you” (Matt. 17:20). In any event, the speaker’s momentary indulgence in the childlike imagination that Rain is eager to leave his sky-home in order to smell the flowers does not indicate idolatry; rather, the speaker’s humble recognition that the rain does what it wills within the scope of God’s permission recalls Gerson’s memorable illustration of subjective right: “the sky has a right to rain.” While it is impossible to know for certain whether Herbert’s use of the pathetic fallacy relies definitively on Gerson’s famed attribution of subjective right to a non-human creature, the constellation of Gersonian ideas and logic appearing in places throughout the poem suggest Herbert was not ignorant of the philosophical significance of his depiction of Rain.

More connections to Gerson’s thinking on natural law and its spiritual implications appear shortly after the speaker apostrophizes Rain. The speaker, having resumed his prayer to Providence, marvels at God’s abundance, recognizing that “Sometimes thou dost divide thy gifts to man, / Sometimes unite” (125-26). To illustrate the latter phenomenon, Herbert employs a classic example of divine bounty, the nut, though he innovates poetically by using a surprising type of nut.48 With the zeal of a New World explorer, the speaker enthuses, “The Indian nut alone / Is clothing, meat and trencher, drink and kan, / Boat, cable, sail and needle, all in one” (126-28). The cascade of examples conduces [→ 308] to awe, as well as lingering reflection. Despite the rush of detail, or perhaps because of it, readers may slow down long enough to ask, how does the coconut yield all these things? In supplying this example, Herbert could have borrowed from ancient sources, but he also could have borrowed from Gerson. In another of the latter’s works, De Theologia Mystica Practica (1407), Gerson encourages his audience to cultivate a reverential imagination, not an idly curious one, such that even a creature as small as a nut may prompt a mystical experience:

You, similarly, in that which you read, hear, see, speak, or think, convert it immediately into affectivity, as if you breathed it from within, smelled, or tasted it […] let your mind rise up immediately and simultaneously to reverence and love, to a trusting request for your needs and those of your brothers, with whom the Father is shared […] We can find such forms of affection without number or end. From one day to the next they will be sweet and new, as if hidden in a honeycomb (Sg. 5:1), in manna, or in a nut. (Gerson, On Mystical Theology 301)

Gerson’s emphasis on the “sweet” discovery of God’s Creation, coupled with his last reference to the nut, may have been memorable enough to inspire Herbert in “Providence.” But even if Herbert did not read De Theologia Mystica Practica, Gerson’s De Vita Spirituali Animae still helps to illumine the spiritual significance of Herbert’s poetic revel in the abundance of the “Indian nut.”

In that latter work, as shown above, Gerson suggests that each creature, rational or non-rational, conforms to divine law via natural law in a multitude of ways, each way appropriate to that creature’s being. The creature’s powers and faculties, that is, the creature’s subjective right, allows that creature to conform to divine law in ways that may or do differ, partly or entirely, from the ways of another creature, such that each creature retains a place in the Great Chain of Being. Although Gerson focuses on rational creatures’ conformities to divine law given his concerns with pastoral care, his logic implies that non-rational creatures also conform variously to divine law. Thus for non-rational creatures as well as rational ones, “multiple rectitudes and goodnesses may [→ 309] coincide” as these creatures obey divine law. Gerson’s provocative understanding of conformity to divine law agrees with Herbert’s brief meditation on the Indian nut. Surely aware that in the Creation account as recorded in Genesis, “God saw euery thing that hee had made: and behold, it was very good,” Herbert portrays his speaker noticing the intrinsic goodness of a humble and yet awesome object (Gen. 1:31). The fact that the coconut has so many uses—bodily covering, physical sustenance, plate, transport, tool—shows Providence at work. Precisely because Providence works in and through the nut’s conformities to divine law, the nut offers what amounts to moral witness indirectly to those who have ears to hear and eyes to see. But for those who struggle to perceive that witness, Herbert concisely articulates how the nut’s abundance signals God’s wise generosity: he declares that the Indian nut “alone” (126) combines “all in one” (128). In a poem full of examples of non-human creatures like the coconut, each conforming to divine law grounded in God’s love, Herbert repeatedly teaches the same Gersonian lesson: the affective contemplation of God’s creatures great and small within and beyond poetry helps to nurture the life of the soul. If readers experience the harmonious magnificence of Creation in reading Herbert’s poem, and especially if that experience humbles and encourages them, then poetry providentially helps readers grow into a truly abundant life.49

To make that goal clear to readers, Herbert dramatizes the speaker’s spiritual transformation as a result of his meditations on Providence. As evidenced above, the speaker’s attitude develops some humility early on in the lyric, when he switches from first-person singular to first-person plural, thereby recognizing himself as a member of a musical chorus of creatures, human and non-human. Yet Herbert does not halt the speaker’s spiritual progress there. Though the speaker celebrates humanity’s ability to labor as God’s “Secretarie” at the beginning of the poem (8), the difficulty of that labor ends the celebration exactly halfway through the poem. At this point, he feels inadequate and longs for help with his writing. The speaker’s earnest questions spotlight his [→ 310] poignant predicament and his willingness to receive whatever help anyone—anyone at all, human or non-human—may offer:

Who hath the virtue to expresse the rare

And curious vertues both of herbs and stones?

Is there an herb for that? O that thy care

Would show a root, that gives expressions! (73-76)

At first, the speaker appears to look for a fellow human to help him write (“Who”). But then, he searches for a fellow non-human to assist him (“an herb”). Providentially, right in the act of wondering what creature (perhaps literally beneath him) he may ask for help to write well, he shows himself writing beautifully, and in some way adding to the Book of Nature.50 Yet because the speaker senses that he is still spiritually out of tune with the ultimate Lyricist, he nevertheless persists in his contemplation of God’s creatures. And what he receives from them is not a confirmation of his superiority or even an assurance of his equality, but a limited awareness of his inferiority. That awareness arrives three stanzas from the poem’s end, when the speaker again feels insecure about his ability to serve as God’s “Secretarie,” and so asks: “But who hath praise enough? nay who hath any?” (141). His second question is particularly powerful since it suggests that his meditation on God’s ways and means has given him an experience of the divine that transcends words, no matter how artful. Consequently, his insecurity about being a good servant is quickly replaced by a stabilizing certainty: “None can expresse thy works, but he that knows them; / And none can know thy works, which are so many, / And so complete, but onely he that owes them” (142-44). The crucial word here in these lines is “owes.” Given what the speaker has shared about God’s Creation and his changing responses to it, Herbert surely intends an aural pun, such that one “owes” Providence when one ‘oh-s’ Providence.51 If so, then it appears that, as in “Sion,” so too here: the best praise of God may be “one good grone” (18). When the speaker lets himself be tempered and tuned, when he conforms himself to God’s law in awe, humility, repentance, gratitude, joy, and especially love, then he is ready [→ 311] to join other creatures—who have perhaps been waiting for him—in the mystical music of the cosmos, that spiritual harmony in and of God.

3. The Council of All Creatures: A Glance at Herbert’s Protestant Conciliarism

So far, I have drawn attention to Herbert’s conviction that humans and non-humans offer providential guidance to those with ears to hear and eyes to see it. Herbert’s belief appears indebted to Gerson’s understanding of divine and natural law, particularly as they shape the cosmos’s mystical music. That music provides the basis for Gerson’s conciliarism. As I have explained above, Gerson thinks that the mystical music of the universe arises from each creature’s multiple conformities to divine law via natural law. Thus, for him, all creatures have intrinsic spiritual significance, even though their actions (or inactions) may not be moral or immoral per se. While humans may offer moral witness to one another directly or indirectly, given their share in divine right reason, non-humans, given their lack of right reason, must provide what amounts to moral witness to humans indirectly. As a result, humans must use their rational faculty especially sensitively to perceive non-humans’ witness. Herbert appears to find aspects of Gerson’s thinking amenable, for in “Providence,” he consistently shows how non-humans, despite lacking fully free will and right reason, provide the speaker the near-moral guidance he needs to humble himself before God and his “fellows.” As the speaker follows this guidance, he allows Providence to tune him spiritually so that he will contribute fairly, that is, justly and beautifully, to the cosmos’ mystical music. Since this concord originates in God, whenever any creature accords with divine law, that creature positions himself to serve “Man” effectively as a member of a proto-Church council working in the temple of the cosmos. In this section, then, I briefly consider Herbert’s Protestant conciliarism, which he likely learned from Gerson, one of conciliarism’s chief champions.52 [→ 312]

Herbert’s subtly provocative adaptation of Gerson’s conciliarism appears throughout “Providence,” but especially in its closing stanzas. There, Herbert reaffirms Gerson’s conviction that non-humans have enough innate goodness to give their human counterparts what amounts to moral witness. This witness, together with Herbert’s decision to anthropomorphize non-humans by assigning them masculine pronouns, means that non-humans function as a proto-church council obliged by God’s laws to help guide “Man” in the use of his priestly authority, especially if he is willing to serve as the “worlds high Priest,” a role that logically necessitates at least some other creatures’ service as lower priests.53 In the poem’s final stanzas, this council appears in lyrical dialogue with the speaker:

All things that are, though they have sev’rall wayes,

Yet in their being joyn with one advise

To honour thee: and so I give thee praise

In all my other hymnes, but in this twice.

Each thing that is, although in use and name

It go for one, hath many wayes in store

To honour thee: and so each hymne thy fame

Extolleth many wayes, yet this one more. (145-52)

Both stanzas show Herbert’s reliance on Gerson’s notion of species-specific conformity to divine law via natural law. In the first stanza, the speaker’s use of the word “things” levels all creatures, humbling Man by placing him in the same category as a thing. Even so, the speaker reasserts Man’s superiority, for though “All things” follow “one advise” of objective right (divine law), all things “have sev’rall wayes” of doing so as determined by subjective right (a creature’s power or faculty). Since Man’s faculty includes versification, the speaker mentions how his past lyrics laud God once, but this lyric does so “twice.” Wilcox parses the speaker’s usage of the word “twice” by observing that one form of praise occurs in “Providence” itself, while another transpires in Herbert’s being as he writes that poem (427n147-8). What scholars miss is that something similar happens to non-humans in the poem’s last [→ 313] stanza. Whereas the penultimate stanza zooms in on the speaker, reestablishing him above other creatures as God’s poet, the ultimate stanza zooms out on all creatures as God’s poems, even His proto-poets. While “Man” is God’s “Secretarie” directly, non-humans are God’s secretaries indirectly. As each creature lives his life in accordance with divine law via the laws of nature inscribed within his body, that body serves God as an instrument of His harmony. From Herbert’s Gersonian perspective, “each” creature is a “him” who is God’s “hymne,” that is, an individual being with spiritual import, one who has personality or something akin to it.

The fact that Herbert dignifies non-human creatures by suggesting that they have something in them that resembles Man, something that evokes human free will and right reason without being either of those things, allows non-human creatures to carry a near-moral message with spiritual significance.54 Although they may carry this message individually, they have great power when they carry it collectively. For when they do the latter, they exert something like conciliar authority to affirm, to tolerate, or to protest the behavior of Man, “the worlds high Priest.” Read this way, “Providence” suggests that De Vita Spirituali Animae influenced Herbert not only through Gerson’s discussion of natural law, but also through the nascent conciliarism that arises within that discussion. Admittedly, the boldness and vehemence of Gerson’s opposition to unjust popes may seem out of line with the subtlety of Herbert’s metaphor of Man as “the worlds high Priest,” especially since Herbert gently distances himself from his speaker when the speaker fails to follow the biblical logic surrounding this role through to its ministerial consequences of shared governance of the Church.55 But Herbert is more than capable of extracting the grains of truth from a text and leaving the rest.56 So in my brief collection of the grains of Gerson’s conciliarism in De Vita Spirituali Animae, I identify those that have the greatest relevance for understanding what Herbert suggests may be the proper balance between human and non-human authority when it comes to living together in God’s world. [→ 314]

In his treatise, Gerson spends much time delineating the differences between divine law, natural law, civil law, as well as mortal and venial sin in hopes of helping readers to know whether they are in danger of losing their salvation during a time when two popes claimed to be legitimate. Because he believes that humans share in God’s right reason, they have the authority and the obligation to challenge unjust rulers, even illegitimate or evil popes. Thus he claims, “if superiors for their own lust are able to throw down, to trample on, to afflict and to destroy their inferiors because it is not permitted to oppose their violence either in word or in deed, then the commonwealth, for whose benefit all power is established, would go badly.”57 Consequently, he contends that it is morally and spiritually acceptable according to divine and natural law to oppose corrupt rulers and popes if there is “an urgent and manifest necessity,” even in cases that affect only “individual persons.”58 Gerson makes it clear that the natural right to oppose and even to kill an unjust Pope applies only to rational creatures:

[T]here are many possible cases in which someone pretending to be the Pope, and having such an attitude from the Church, may be lawfully killed or imprisoned by a subject, or [experience] a withdrawal from the power of his obedience once rejected, unless perhaps someone could show that some revealed constitution stands in the way, because some human constitution is not able to abolish this natural right; for it is founded on the title of natural existence communicated by God to the rational creature.59

Gerson’s stipulation that the right to protest bad papal conduct stems from the right to self-preservation allows him to address the pastoral care crisis brought about by the Western Schism.60 But because of his focus on caring for souls, he does not state what he and others know: the God-given right of self-preservation applies to non-rational creatures, too.

Given Gerson’s assumption that only humans have the need and the natural right to resist or to remove a grossly abusive Pope, he could not have imagined that anyone would apply his words to non-humans, however figuratively and wittily. Yet “Providence” shows Herbert doing just that. Throughout the poem, as I have shown, one or more non- [→ 315] humans indirectly indicate that “Man” ought to realign himself with divine law via natural law, and thereby experience the sweet power of being in harmony with God and the rest of Creation. Because Herbert portrays Man as “the worlds high Priest,” it is unclear whether he agrees with Gerson’s adage, “as the Pope is the superior of all, so he is the servant of all.”61 The closest Herbert comes to stating that Man is the servant of all occurs when the speaker avers that Man “doth present / The sacrifice for all,” a proud claim that is technically true, but spiritually false, as the rest of the poem proves. Still, Herbert brings his speaker to that point when he realizes that he “owes” the rest of Creation, and that sense of indebtedness to non-humans implies that the speaker must work to repay them in a way that goes beyond writing. Insofar as Herbert turned to Gerson for ideas on this point, it is worth noting that Gerson specifies that a good Pope will work for the Church “as their superior and guardian and preserver.”62 Should he fail in one or all of these areas, members of the Church may try to correct him fraternally using these laws.63 If he refuses to be corrected, then members may report him to the Church council, which has the power and authority to denounce him if he ignores their rebuke.64 Gerson contends, “But if he does not convene the council as lawfully required, and nevertheless persists in his offenses, he may himself be regarded as truly obstinate, not ready to listen to the Church.”65 In such a defiantly transgressive state, the Pope is vulnerable to a just and potentially fatal overthrow. Gerson’s idea that a Church council is greater than a Pope has implications that he does not parse in the De Vita Spirituali Animae. But in “Providence,” Herbert investigates poetically some of the metaphoric consequences of Gerson’s bold logic, depicting the ways in which Man, the cosmos’ worship leader, may realign himself with God and neighbor, human and non-human, thereby deepening the life of his soul and providentially helping to preserve the lives of his fellow creatures.

To the extent that “Providence” articulates humanity’s need to humble itself relative to other creatures in order to live better with them in [→ 316] acts of loving stewardship, the poem offers multiple ways for its audiences to reconsider humanity’s place in the cosmos and especially on Earth. For twenty-first-century readers dealing with the effects of global climate change, “Providence” makes what now may seem like either a tired or refreshing argument: hubristic humanism needs urgent treatment using philosophical and theological tools. The fact that “Herbert the eco-warrior,” in Russell M. Hillier’s incisively witty locution, apparently borrowed some of these tools from Gerson and poetically repurposed them invites further examination (641).66 For example, does Gerson’s understanding of natural law and mystical theology in the De Vita Spirituali Animae and/or the twin treatises, De Mystica Theologia Speculativa and De Mystica Theologia Practica, influence other poems in The Temple? What may Gerson’s three treatises on mystical music say about Herbert’s own approach to God’s “musick,” whether in “Providence” or in other lyrics such as “Church-musick,” “Antiphon [I],” “Antiphon [II],” or “Heaven”? After all, “Man,” a companion poem of sorts to “Providence,” suggests that “Musick and light attend our head” (33), and so may well owe something to Gerson’s spiritually resonant cosmos.67 Surely a fuller understanding of how Herbert creatively adapts Gerson’s belief in the legal basis for mystical music would complement readers’ knowledge of how The Temple “attempts visually (and descriptively) to evoke the harmonic structures of liturgical music” (Prakas 85). As technological innovation renders more of the universe audible, thereby recalling medieval and early modern notions of a cosmic harmony, Herbert’s Gersonian perspective in “Providence” will invite hopefully readers to imagine other ways that The Temple draws on medieval and early modern scholarship in a concerted effort to improve readers’ spiritual sight and hearing.68

Works Cited

Balla, Angela. “Baconian Investigation and Spiritual Standing in Herbert’s The Temple.” George Herbert Journal 34.1-2 (Fall 2010-Spring 2011): 55-77.

“Black Hole at the Center of Galaxy M87.” New NASA Black Hole Sonifications with a Remix, Chandra X-Ray Observatory, https://chandra.si.edu/photo/2022/sonify5/. 23 June 2024.

Benet, Diana. Secretary of Praise: The Poetic Vocation of George Herbert. Columbia, MO: U of Missouri P, 1984.

Brett, Annabel S. Liberty, Right, and Nature: Individual Rights in Later Scholastic Thought. Cambridge: CUP, 1997.

Calloway, Katherine. “A Particular Trust: George Herbert and Epicureanism.” Connotations 32 (2023): 114-44. https://www.connotations.de/article/a-particular-trust-george-herbert-and-epicureanism/.

Church of England. “The Advent Antiphons.” Advent. https://www.churchofengland.org/prayer-and-worship/worship-texts-and-resources/common-worship/churchs-year/times-and-seasons/advent#mmm20. 28 May 2024.

Donne, John. The Variorum Edition of the Poetry of John Donne. Vol. 2. Gen. ed. Gary A. Stringer. Bloomington: Indiana UP, 2000.

Donne, John. The Variorum Edition of the Poetry of John Donne. Vol. 7, part 1. Gen. ed. Gary A. Stringer. Bloomington: Indiana UP, 2005.

Dyck, Paul. “The Providential Rose: Herbert’s Full Cosmos and Fellowship of Creatures.” Connotations 33 (2024): 259-84. https://www.connotations.de/article/the-providential-rose-herberts-full-cosmos-and-fellowship-of-creatures/.

“Galactic Center Sonification.” A Universe of Sound, Chandra X-Ray Observatory, https://chandra.si.edu/sound/#gcenter. 23 June 2024.

Gerson, Jean. “De Vita Spirituali Animae.” Jean Gerson: Œuvres complètes. 10 vols. Ed. Palemon Glorieux. Paris: Desclée & Cie, 1962. 3: 113-202.

Gerson, Jean. Plures tractatus de canticis, Joannis Gerson opera omnia. Vol. 3. Ed. Ellies du Pin. Antwerp, 1706.

Gerson, Jean. On Mystical Theology: Second Treatise. Jean Gerson: Early Works. Trans. Brian Patrick McGuire. New York: Paulist P, 1998.

Guibbory, Achsah. Christian Identity: Jews and Israel in Seventeenth-Century England. Oxford: OUP, 2010.

Guite, Malcolm. “O Sapientia an Advent Antiphon.” Malcolm Guite, 17 Dec. 2020, 9:01 a.m., https://malcolmguite.wordpress.com/2020/12/17/o-sapientia-an-advent-antiphon-6/. 28 May 2024.

Herbert, George. The English Poems of George Herbert. Ed. Helen Wilcox. Cambridge: CUP, 2007.

Herbert, George. The English Poems of George Herbert. Ed. G. H. Palmer. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1916.

Herbert, George. The Works of George Herbert. Ed. F. E. Hutchinson. Oxford: OUP, 1941.

Hillier, Russell M. “‘Send back thy fire again’: Praise, Music, and Poetry in the Lyrics of George Herbert,” The Modern Language Review 111.3 (July 2016): 633-64.

Hodgkins, Christopher. “‘Gerson, a Spirituall Man’: Herbert and the University of Paris’s Reformist Chancellor.” Edward and George Herbert in the European Republic of Letters. Ed. Greg Miller and Anne-Marie Miller-Blaise. Manchester: Manchester UP, 2022. 119-39.

Hodgkins, Christopher. “‘Yet I love thee’: The ‘Wayes of Learning’ and ‘Groveling Wit’ in Herbert’s ‘The Pearl.’” George Herbert Journal 27.1-2 (Fall 2003-Spring 2004): 22-31.

Hoffman, Tobias. “Intellectualism and Voluntarism.” The Cambridge History of Medieval Philosophy. Ed. Robert Pasnau. Cambridge: CUP, 2009. 414-27.

Holy Bible: 1611 Edition. Nashville, TN: Thomas Nelson, 1982.

Ilnitchi, Gabriela. “Musica Mundana, Aristotelian Natural Philosophy and Ptolemaic Astronomy.” Early Music History 41 (2002): 37-74.

Idziak, Janine. “God’s Will as the Foundation of Morality: A Medieval Historical Perspective.” Religions 12 (2021): https://doi.org/10.3390/rel12050362. 30 May 2024.

Irwin, Joyce L. “The Mystical Music of Jean Gerson.” Early Music History 1 (1981): 187-90.

Jonson, Ben. “To Penshurst.” The Cambridge Edition of Ben Jonson’s Works Online. Ed. by Colin Burrow. https://universitypublishingonline.org/cambridge/benjonson/k/works/forest/facing/#. 27 March 2024.

Mazour-Matusevich, Yelena. “Gerson’s Legacy.” A Companion to Jean Gerson. Ed. Brian Patrick McGuire. Leiden: Brill, 2006. 357-99.

Mazour-Matusevich, Yelena. Le père du siècle: The Early Modern Reception of Jean Gerson (1363-1429) Theological Authority between Middle Ages and Early Modern Era. Turnhout: Brepols, 2023.

McGuire, Brian Patrick. Jean Gerson and the Last Medieval Reformation. University Park: Pennsylvania State UP, 2005.

Mollenkott, Virginia R. “The Many and the One in George Herbert’s ‘Providence.’” CLA Journal 10.1 (September 1966): 34-41.

Oakley, Francis. “Gerson as Conciliarist.” A Companion to Jean Gerson. Ed. Brian Patrick McGuire. Leiden: Brill, 2006. 179-204.

Pease, A. S. “Things Without Honour.” Concerning Poetry 21 (1926): 27-42

Prakas, Tessie. Poetic Priesthood in the Seventeenth Century: Reformed Ministry and Radical Verse. Oxford: OUP, 2022.

Rienstra, Debra K. “‘I Wish I Were a Tree’: George Herbert and the Metamorphoses of Devotion.” Connotations 32 (2023): 145-64. https://www.connotations.de/article/debra-k-rienstra-i-wish-i-were-a-tree-george-herbert-and-the-metamorphoses-of-devotion/.

“Secretary, N. (1-3).” Oxford English Dictionary, OUP, 2024, https://www.oed.com/dictionary/secretary_n1?tab=meaning_and_use&tl=true#23666113. 23 June 2024.

Tierney, Brian. The Idea of Natural Rights: Studies on Natural Rights, Natural Law, Church Law, 1150-1625. Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1997.

Tierney, Brian. Liberty & Law: The Idea of Permissive Natural Law, 1100-1800. Washington, D. C.: The Catholic U of America P, 2014.

Todd, Richard. “‘Providence’: Reading the Book of Nature.” The Opacity of Signs: Acts of Interpretation in George Herbert’s The Temple. Columbia, MO: U of Missouri P, 1986. 83-112.

Walsham, Alexandra. Providence in Early Modern England. Manchester: Manchester UP, 1999.

Williams, Thomas. “Intellect and Will.” The Cambridge Companion to Medieval Ethics. Ed. Thomas Williams. Cambridge: CUP, 2018. 238-56.

Ring out, wild bells, to the wild sky,

Ring out, wild bells, to the wild sky,