An Introduction to Metagenre with a Postscript on the Journey from Comedy to Tragedy in E. M. Forster's Where Angels Fear to Tread

Burkhard Niederhoff

Published in Connotations Vol. 31 (2022)

Abstract

The article defines metagenre as a quality or dimension of a literary text: the way the text reflects on the genre it belongs to (which includes a consideration of adjacent or opposed genres). We may distinguish between explicit metagenre, which is relatively infrequent, and implicit metagenre. The latter can be further divided into three types: mise en abyme or genre within genre; transtextual references to prototypical examples of the genre (quotation, allusion, parody, etc.); and conspicuous deviations from or violations of genre conventions. The textual strategies associated with metafiction and other meta-terms are seen as self-undermining and self-repudiating by some theorists. This view, however, does not apply to metagenre, at least not to its most interesting cases, which can best be described as probing and dynamic self-definitions that rely both on affirmations and rejections.

A text of this kind is E. M. Forster’s first novel Where Angels Fear to Tread (which contains both explicit and implicit metagenre). The analysis of this novel is based on Forster’s statement that “the object of the book is the improvement of Philip,” its protagonist. This improvement follows Forster’s imperative to “connect,” which has a psychological and a social dimension. Connecting the fragments of one’s personality means connecting with other people and transcending cultural or political barriers in the process. Philip’s improvement is accompanied by a shift from comedy to tragedy, which echoes the history of the genre (while the novel defined itself in comic terms in the long eighteenth century, it increasingly turned to tragic models in the nineteenth). An interesting problem arises in the final chapters, in which Philip is pushed back into the role of an aesthetic observer, which, as part of his improvement, he has previously abandoned in favour of responsibility and involvement. This problem can be solved, however, if one takes the shift from comedy to tragedy into consideration. In the final chapters, Philip changes from a comic into a tragic observer, which means that he is more sympathetic and involved than he used to be.

1. Introduction

At the end of A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Theseus, the newly-wed Duke of Athens, has to choose an entertainment “[t]o wear away this long age of three hours / Between our after-supper and bed-time” (5.1.33-34). He decides in favour of “Pyramus and Thisbe,” a tragedy performed by a group of Athenian tradesmen. One of the rival options is described—and rejected—as follows:

‘The thrice three Muses mourning for the death

Of learning, late deceas’d in beggary’?

That is some satire, keen and critical,

Not sorting with a nuptial ceremony. (5.1.52-55)

In this passage, a character makes a sensible choice how to be entertained—or rather not to be entertained—at his wedding. At the same time, however, the author is making a point about the play itself. The learned writers of Shakespeare’s time think of comedy as an anatomy of vice and folly, a dramatic genre that “make[s] men see and shame at their own faults,” as Sir John Harington argues in “An Apology for Ariosto” (313). In other words, these writers see comedy as a close relative of satire. But Shakespeare’s comedies are not satiric. Instead of exposing vice and folly, they celebrate love and wit. This is why Shakespeare puts a rejection of satire in Theseus’ mouth, thus defining and defending his own brand of comedy.

Theseus’ speech might be described as an instance of metagenre, a self-reflexive statement through which a literary text comments on the genre it belongs to. The present article is meant to give an introduction to this concept and to a series of articles which originated in the Connotations conference on metagenre in the summer of 2021.1) The outline is as follows. This introduction (1) will be followed by a definition (2), a typology (3), a claim about the agenda or import of metagenre (4), and, finally, a reading of E. M. Forster’s first novel Where Angels Fear to Tread (5). Forster’s novel has [→ page 3] been chosen for its intrinsic merits but also because it illustrates the claim that will be made in part 4: metagenre is not as self-undermining and deconstructive as the forms and structures associated with metafiction and comparable meta-terms are often made out to be.

2. Definition

The term metagenre has been used much less than metafiction or metadrama. But like these, it has been employed in a variety of senses. In articles by North American teachers of composition, it refers to an awareness of the rules and conventions governing a particular text type such as a newsletter, a student essay or a medical report; it is primarily a didactic and somewhat prescriptive concept.2) In literary studies, it tends to be employed as a broad term embracing more specific terms such as metabiography, metasonnet, metacomedy, etc. These terms often indicate self-reflexiveness—but by no means invariably. In Alexander Pettit’s “Comedy and Metacomedy: Eugene O’Neill’s Desire Under the Elms and Its Antecedents,” for instance, metacomedy means something like experimental comedy or problem play.3) In contrast to this usage, which I consider too vague, I would like to insist on the aspect of self-reflexiveness, by analogy with the way linguists use the term metalanguage. This is defined by the OED as “a language or set of terms used for the description or analysis of another language”; it entered the English language, according to the same source, in 1936. Linguists distinguish between the metalanguage (typically of a technical or scholarly sort, such as grammar) and its object language (the non-technical, ordinary language that is analysed by means of the metalanguage). In literary studies, this distinction exists as well. A reading of A Midsummer Night’s Dream will employ the metalanguage of theory and criticism (blank verse, rhyming couplets, Petrarchism, etc.) to analyse the object language of the play. However, this is not, or not precisely, what we are concerned with. We need to go one step further than the linguists because we are interested in the theory and criticism that A Midsummer Night’s Dream and other literary works provide about themselves. When the speaker of Shakespeare’s “Sonnet 18” says, “So long as men can breathe or eyes can see, / So long lives this, and this gives life [→ page 4] to thee” (147; emphasis added), he is not using a technical metalanguage to write about an ordinary or literary object language. The sonnet, especially the line in italics, refers not to other texts but to itself. Self-reflexiveness has been brought to the point where metalanguage and object language are the same. This is how terms with the prefix meta are used in literary studies and how the term metagenre will be used in the present article.

For the sake of terminological clarification, I would like to draw a further distinction, using the example of metafiction, probably the most popular of the numerous meta-terms. Many critics use it to refer to a work of fiction that refers to itself in one way or another (meaning no. 1). However, it can also be defined more narrowly as a work that refers to its own fictionality (meaning no. 2). Laurence Sterne’s Tristram Shandy contains numerous examples of the first meaning, for instance, the famous passage in which the first-person narrator discovers that he lives much faster than he can write, and that he will never be able to catch up with himself:

I am this month one whole year older than I was this time twelvemonth; and having got, as you perceive, almost into the middle of my fourth volume—and no farther than to my first day’s life—’tis demonstrative that I have three hundred and sixty-four days more life to write just now, than when I first set out; so that instead of advancing, as a common writer, in my work with what I have been doing at it—on the contrary, I am just thrown so many volumes back—was every day of my life to be as busy a day as this—And why not?—and the transactions and opinions of it to take up as much description—And for what reason should they be cut short? as at this rate I should just live 364 times faster than I should write—It must follow, an’ please your worships, that the more I write, the more I shall have to write—and consequently, the more your worships read, the more your worships will have to read.

Will this be good for your worships eyes? (4: 207; ch. 14)

This passage is metafictional only in the first and broader sense. Evidently, it refers to itself, being one of the digressions that amplify the narrative and slow down the narrator Tristram in his pursuit of the character Tristram. However, the passage is not metafictional in the second, narrower sense. Tristram elaborates on the difficulties of writing his own life, but he does not point out that he owes his existence to the fertile imagination of Sterne, and that he inhabits a work of fiction. For an admission of this sort, we have to go elsewhere, for instance to John Fowles’s The French Lieutenant’s [→ page 5] Woman. At the end of chapter 12, the narrator asks a question about the enigmatic woman referred to in the title of the novel:

Who is Sarah?

Out of what shadows does she come? (94)

The answer is given at the beginning of chapter 13:

I do not know. This story I am telling is imagination. These characters I create never existed outside my own mind. (95)

The speaker of these sentences is no longer the narrator but the author. He is admitting or rather foregrounding the fictionality of his story (and will remain in this mode for almost the entire chapter, presenting a paradoxical argument about his own loss of control and the freedom that his characters gain as they emancipate themselves from their author).

In the two meanings of metafiction that I have distinguished, the emphasis falls on a different part of the term: metafiction (no. 1) and metafiction (no. 2). In the second, fiction (in the sense of “fictionality”) is the object of self-reflexiveness. In the first, fiction (in the sense of “literary narrative”) is the subject of self-reflexiveness, while the object remains undefined; any aspect of the text (style, credibility, the reader, etc.) can become the object or focus of its self-examination.4)

A similar distinction can be made in the case of metagenre. Genre, or rather a particular genre, can be treated as the subject of self-reflexiveness (meaning no. 1). A metagenre, then, is a particular genre (a metacomedy, a metasonnet, etc.) that is self-reflexive in one way or another. Alternatively, genre can be treated as the object of self-reflexiveness (meaning no. 2). The term loses its indefinite article and refers no longer, strictly speaking, to a genre, i.e. to a group or corpus of texts. Instead, it turns into a quality or dimension of a text (in the same way in which some theorists avoid treating literature as a corpus of texts and prefer to talk about literariness, a quality that a text, even a telephone directory, may have to a greater or lesser extent). Consider the following dialogue from A Midsummer Night’s Dream, in which the tradesmen are debating how to present moonlight on the stage:

[→ page 6]

Bottom. Why, then may you leave a casement of the great chamber window, where we play, open; and the moon may shine in at the casement.Quince. Ay; or else one must come in with a bush of thorns and a lantern, and say he comes to disfigure or to present the person of Moonshine. (3.1.52-57)

The dialogue provides an instance of metagenre or metacomedy according to meaning no. 1 as it satisfies the criterion of self-reflexiveness. It refers to a problem that Shakespeare and the Lord Chamberlain’s Men were faced with in performing A Midsummer Night’s Dream no less than Bottom and Quince are in staging “Pyramus and Thisbe” at Theseus’ palace. However, the dialogue is not an instance of meaning no. 2. While it discusses a general problem of theatrical representation, it does not contribute to defining the genre of A Midsummer Night’s Dream, as Theseus’ rejection of satire does, which furnishes a good example of meaning no. 2.

Many critics use the various meta-terms in the first, more inclusive sense, either not being aware of or not sufficiently caring about the second, narrower sense. In one of the standard books on metafiction, Patricia Waugh, for instance, defines the term very broadly. In the subtitle she paraphrases the term as “self-conscious fiction,” thus including all sorts of self-reflexiveness. Janine Hauthal, one of the few critics to have used the term metagenre so far, also thinks along these lines. While she is aware of the distinction between the two meanings, she also prefers the first, more inclusive one. In the subtitle of her article, she refers to “novelistic meta-genres,” a plural that indicates that she does not think of metagenre as a quality or dimension of a text. By contrast, I would like to make a case for the second, narrower meaning. While the early studies of self-reflexiveness in literature, such as Waugh’s book, have treated the subject in broad terms, recent studies have attempted to introduce more precise definitions and typologies that distinguish between different kinds of self-reflexiveness. A narrower definition of the term, then, is in line with the general tendency in the scholarly work on the subject. In addition, using the term in the broad sense means that the category of genre remains curiously irrelevant. Analysing A Midsummer Night’s Dream as a metacomedy only makes sense if the genre of comedy and related genres such as satire play a significant role [→ page 7] in the analysis. If this is not the case, one should leave genre out of the terminology and simply talk about metatextuality or self-reflexiveness.

Treating our concept as a quality rather than a genre still allows for the question whether some genres are more favourable to this quality than others. A candidate that immediately comes to mind is parody, especially genre parodies such as the mock epic. However, this raises the question whether parody should be considered a genre in its own right, or a parasitic mode that attaches itself to other genres. In the context of the present argument, the latter option seems preferable; after all, a genre parody typically does not foreground its own mechanisms but those of the genre it is imitating in a comic or ludic fashion. Therefore, I will discuss parody in the third part of this article, which distinguishes different types or modes of metagenre. A second candidate or group of candidates consists of genres with particularly strict and obvious rules, such as the sonnet, the villanelle or the detective story. Support for this claim comes from Matthias Bauer’s introduction to an earlier themed section of this journal, “Self-Imposed Fetters: The Productivity of Formal and Thematic Restrictions.” Bauer discusses three self-reflexive sonnets that comment on the formal constraints imposed by this demanding genre; in different ways, the poets struggle with and ultimately embrace the constraints, discovering them to be productive and liberating. However, it would be premature to delimit the discussion to genres with very strict rules. At the Connotations conference on metagenre, papers were given on tragedy, the epic, stand-up comedy, pastoral poetry, the verse essay, six-word stories, the short story, the novel, the memoir-novel, and dramatic burlesques. At one point, a discussion erupted around the question whether it is the rigidity of genre rules, as in the sonnet, or rather their flexibility and looseness, as in the novel, that provides the best habitat for metagenre. The latter view is supported by Hauthal, who writes that “[t]he emergence of several meta-genres at once suggests that the novel is especially responsive to metaization and its dynamics of generic change” (89).5)

Before embarking on the typology, I would like to add a final point. I have made a case for a narrow definition of metagenre: the self-examination of a literary text that is focused on, and limited to, its own genre. I would like to broaden this definition in one respect. The phrase “its own [→ page 8] genre” should not be taken to mean that a comedy can only focus on the conventions of comedy, a sonnet only on the conventions of the sonnet, etc. In the introductory example from A Midsummer Night’s Dream, we have seen that Shakespeare defines his type of comedy by distinguishing it from satire; he also uses the tragedy, or the mock-tragedy, of “Pyramus and Thisbe” for the same purpose. Moreover, a literary text can belong to or describe itself as belonging to more than one genre. In Where Angels Fear to Tread, Forster defines his type of novel by relating it to two other genres, comedy and tragedy. “Genres are better understood,” writes Alastair Fowler, “through a study of their mutual relations” (255), a remark that applies not only to the efforts of the critic and the theorist but also to the instances of metagenre that we find in literary works themselves.

3. Typology

A number of scholars have proposed typologies to chart the field of self-reflexiveness in narrative, in literature and in the arts in general. Not all of the types distinguished by these scholars are relevant to metagenre. Werner Wolf, for instance, includes what Roman Jakobson considers the poetic function of texts, i.e. the phenomena described with the formula “[s]imilarity superimposed on contiguity” (metre, rhyme, parallelism, etc.).6) These phenomena can be safely excluded, to my mind, from a typology of metagenre. Admittedly, rhyme and parallelism can become metageneric (for instance if they are used in parodic ways), but they are not metageneric as such. In the following remarks, I will draw on the typologies devised so far,7) but I will limit the discussion to the types that are relevant to our subject.

A first distinction should be drawn between explicit and implicit metagenre. Fully explicit examples are rare. They have to name a genre and draw a connection to the text itself. Theseus’ comment in A Midsummer Night’s Dream only satisfies the first criterion but not the second. He is explicit about the genre (“satire”) and some of its salient features (“keen and critical”), but not about the connection between this genre and the play itself; this connection is left for the audience and the critic to discover or to [→ page 9] ignore. An example of explicit metagenre that leaves nothing to be desired comes from John Dickson Carr’s The Hollow Man,8) a murder mystery whose detective is well aware of the conventions of the murder mystery:

“I will now lecture,” said Dr Fell, inexorably, “on the general mechanics and development of the situation which is known in detective fiction as the ‘hermetically sealed chamber.’ Harrumph. All those opposing can skip this chapter. Harrumph. To begin with, gentlemen! Having been improving my mind with sensational fiction for the last forty years, I can say—”

“But, if you’re going to analyse impossible situations,” interrupted Pettis, “why discuss detective fiction?”

“Because,” said the doctor, frankly, “we’re in a detective story, and we don’t fool the reader by pretending we’re not.” (152)

In this passage, the genre is identified (detective fiction), a conventional plot element is pointed out (the locked-room murder initiated by E. A. Poe’s “The Murders in the Rue Morgue”), and it is made abundantly clear that Dr Fell’s lecture, which takes up an entire chapter, has a bearing on the novel in which it is given. One of the listeners remarks that the lecture has “some application to this case” (154)—i.e. the case that Dr Fell will solve at the end of the novel—and the lecture is frequently interrupted by discussions as to whether the various solutions of locked-room murder mysteries in detective novels provide a key to the murders in The Hollow Man.

In implicit metagenre, the genre status of a text is only suggested, not pointed out in the obvious and direct manner of Dr Fell’s lecture. Implicit metagenre can be further divided into three types. The first is what André Gide calls mise en abyme. By analogy with such terms as the play within the play or the novel within the novel, one might also refer to this as genre within genre. A good example of this has been mentioned more than once: the performance of “Pyramus and Thisbe” at the end of A Midsummer Night’s Dream. This performance is well described as “tragical mirth” (5.1.57), collapsing as it does into farce and laughter in the performance given by Bottom and his fellow tradesmen. As such, it contributes to the argument about genre that Shakespeare provides. It suggests the uncanny proximity of comedy and tragedy, at least in their initial plot situations (which are very similar in A Midsummer Night’s Dream and “Pyramus and Thisbe”), [→ page 10] and it contributes to the ultimate transformation of tragic potential into a comic outcome.9)

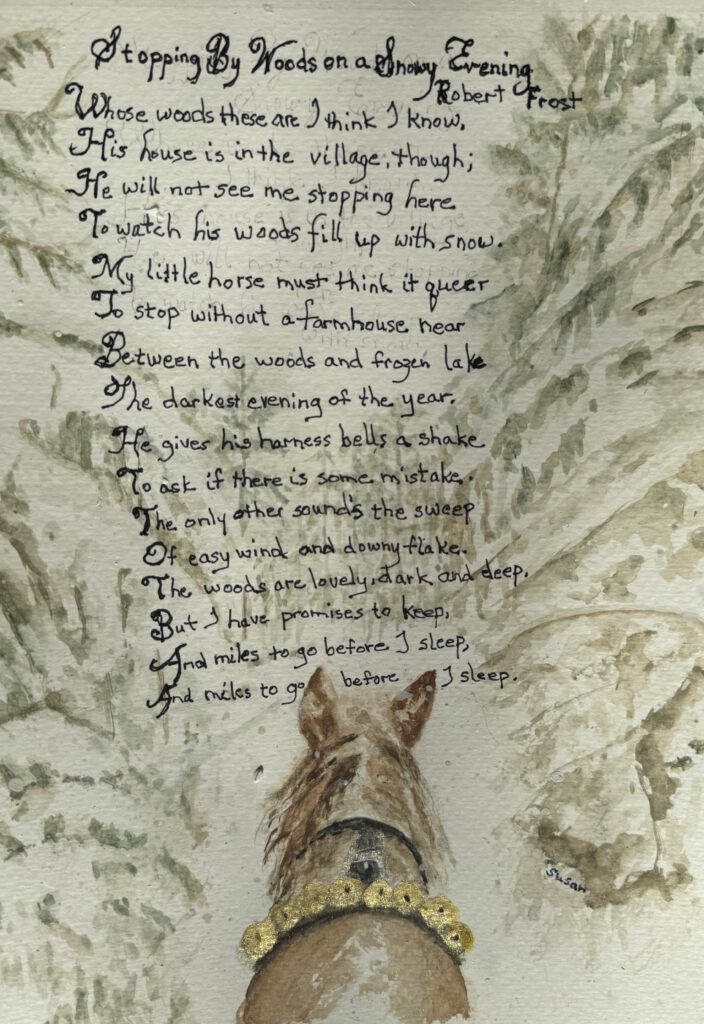

The second type of implicit metagenre is transtextual, which means that a text invokes a genre by referring to a prototypical example of this genre.10) In Jane Austen’s Emma, for instance, the eponymous character quotes a well-known verse from A Midsummer Night’s Dream:

“[…] There does seem to be a something in the air of Hartfield which gives love exactly the right direction, and sends it into the very channel where it ought to flow.

The course of true love never did run smooth—

A Hartfield edition of Shakespeare would have a long note on that passage.” (73)

In this speech, Emma displays her characteristic blend of cleverness and foolishness, implying that matches at Hartfield are made in a harmonious manner under her benign and astute direction. Austen, however, indicates that the course of true love in Emma will be as chaotic and circuitous as in Shakespeare’s play, and she also acknowledges the debt that her novels owe to the rich tradition of English stage comedy. Prototypical examples of a genre may also be invoked through allusions, as in Where Angels Fear to Tread: “Not Cordelia nor Imogen more deserve our tears,” (47) the narrator comments on Lilia Herriton, the Englishwoman who marries and dies in a small town in Tuscany. He also compares her husband Gino to Hamlet (102), and has Philip and Harriet Herriton, her brother- and sister-in-law, visit the “tomb of Juliet” in Verona (75).

Instead of such small-scale references, “intertextual” in the terminology of Gérard Genette, writers may also resort to “hypertextuality,” i.e. to the large-scale borrowings of parody, travesty, etc. in which an entire text or a great part of it is modelled on a previous text.11) Parody is especially relevant for two reasons. First of all, it may be based on a genre rather than a single text, as is shown by MacFlecknoe, The Rape of the Lock and other mock epics of the neoclassical period. Even single-text parodies often target a famous or prototypical example of a genre and are thus relevant to our subject. In Shamela, for instance, Henry Fielding satirises not only the pseudo-morality of a particular novel, Samuel Richardson’s Pamela; he also ridicules the technique of “writing to the moment,” which has a more general [→ page 11] bearing on the conventions of the epistolary novel. Secondly, parody is singularly apt to foreground genre conventions. One of its characteristic techniques consists in maintaining the form while lowering or trivialising the content. Thus form and content are pulled apart, with the result that the formal conventions of the text are laid bare and exposed. They become the subject of the reader’s attention and, possibly, of metageneric reflections.12)

Texts may draw the reader’s attention to genre conventions not only by means of parody; they may also foreground these conventions by violating or deviating from them. This, I would like to suggest, is the third type of implicit metagenre. The ending of Bernard Shaw’s Pygmalion, for instance, raises the question whether the play is a comedy, an anti-comedy or a new development of the genre, an adaptation to the cultural conditions of the early twentieth century. In a traditional comedy, young lovers have to overcome the opposition of their parents or guardians in order to get married, and their final union is celebrated as a victory of love and passion over financial prudence. Pygmalion reverses this pattern in that Mr Doolittle gets married against the will of his daughter, and his marriage amounts to a victory of financial prudence over love and passion. Further examples can be found in the sonnets of E. E. Cummings, who frequently and recognisably uses this genre, but almost never without drastic changes or deviations. In her article “The Modernist Sonnet and Pre-Postmodern Consciousness: The Question of Meta-Genre in E. E. Cummings’ W [ViVa] (1931),” Gillian Huang-Tiller argues “that Cummings takes the sonnet to the level of meta-genre” (157), that his “long-standing engagement with the sonnet form is not a mere modernist experiment or desire to innovate with the traditional form and its themes, but is rather a self-reflexive structuring that bares the bones of the genre itself, conveying a larger theme of the relation of form to cultural reality” (156). The reflections on the genre are thus embedded in more general reflections about man-made forms and structures.

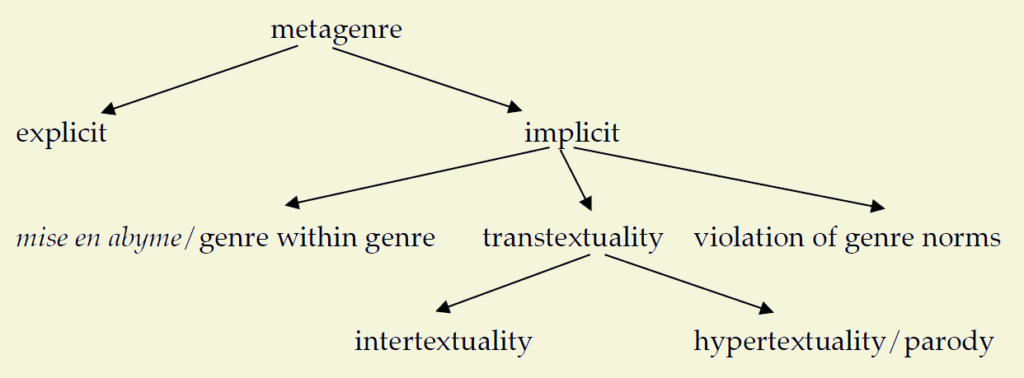

[→ page 12] The types distinguished thus far may be presented as follows:

Needless to say, the neat division of branches in this diagram is a simplification. The reality that we encounter in reading actual texts is more mixed; examples that clearly fit one, and only one, of the categories distinguished here are the exception rather than the rule. I have already indicated that explicitness is a matter of degree, Theseus’ comment on satire being less explicit than Dr Fell’s lecture on detective novels. Moreover, the types may easily combine with each other. The performance at the end of A Midsummer Night’s Dream exemplifies genre within genre (implicit type no. 1), but it is also an instance of hypertextuality: a parody of the episode of Pyramus and Thisbe in Ovid’s Metamorphoses (implict type no. 2). One might also argue that the parodic foregrounding of a genre convention (implicit type no. 2) does not substantially differ from the violation of a genre convention (implicit type no. 3). While the distinction seems clear enough in some cases—E. E. Cummings’ deviations from the Petrarchan or Shakespearean rhyming patterns are not parodic—, it would be more difficult to uphold in others.

I would like to conclude this section with a final methodological question. How far can we go in pursuing implicit metagenre? Consider the opening paragraph of Where Angels Fear to Tread:

They were all at Charing Cross to see Lilia off—Philip, Harriet, Irma, Mrs Herriton herself. Even Mrs Theobald, squired by Mr Kingcroft, had braved the journey from Yorkshire to bid her only daughter goodbye. Miss Abbott was likewise attended by numerous relatives, and the sight of so many people talking at once and [→ page 13] saying such different things caused Lilia to break into ungovernable peals of laughter.

“Quite an ovation,” she cried, sprawling out of her first-class carriage. “They’ll take us for royalty. Oh, Mr Kingcroft, get us foot-warmers.” (1)

No-one in their right minds would or should think of metagenre when they read this passage for the first time. But a little later we learn that Lilia’s mother responds to her daughter’s farewell with tears. Further on, we read about the “inevitable tragedy” (31) of Lilia’s marriage and about Philip’s preference for treating life as a comedy—a preference that is presented as highly problematic. Retrospectively, the first paragraph assumes an added meaning and can be interpreted as an instance of implicit metagenre: a comic response that is excessive and inappropriate. Similarly to Philip, Lilia is a tragic character who foolishly behaves as if she were inhabiting a comedy. Such a reading seems to me justified because of the many explicit references to genre which sharpen our vision in discerning the implicit references. But what about the “royalty” in the second paragraph? Can this be considered an allusion to tragedy, considering the old norm that tragedy is about the downfall of princes whereas comedy presents bourgeois folly? Probably not, but there are no hard and fast rules about how far to go and where to stop in pursuit of implicit instances. Metagenre is not just a feature of the text but also a way of interpreting it. And, as such, it requires both imagination and discrimination.

4. The Import of Metagenre

The self-reflexiveness associated with the various meta-terms is often seen as critical, subversive or deconstructive, especially by those who consider it a salient feature of postmodern or twentieth-century literature. Waugh argues along these lines in her study of metafiction:

In modernist fiction the struggle for personal autonomy can be continued only through opposition to existing social institutions and conventions. This struggle necessarily involves individual alienation and often ends with mental dissolution. The power structures of contemporary society are, however, more diverse and more [→ page 14] effectively concealed or mystified, creating greater problems for the post-modernist novelist in identifying and then representing the object of “opposition”.

Metafictional writers have found a solution to this by turning inwards to their own medium of expression, in order to examine the relationship between fictional form and social reality. They have come to focus on the notion that “everyday” language endorses and sustains such power structures through a continuous process of naturalization whereby forms of oppression are constructed in apparently “innocent” representations. The literary-fictional equivalent of this “everyday” language of “common sense” is the language of the traditional novel: the conventions of realism. Metafiction sets up an opposition, not to ostensibly “objective” facts in the “real” world, but to the language of the realistic novel which has sustained and endorsed such a view of reality.

The metafictional novel thus situates its resistance within the form of the novel itself. (10-11)

According to Waugh, the conventions of language and literature are by definition suspect, and metafictional writers are like detectives or investigative journalists in the corrupt world of textuality. Their task is to unmask the text, to disclose sinister meanings behind innocuous facades. Self-reflexiveness equals self-criticism or even self-repudiation.

Waugh’s assumptions doubtless apply to some texts and some writers. They fit the plays of the German dramatist Bertolt Brecht (or at least Brecht’s own view of his plays); the so-called Verfremdungseffekt, the disruption of the theatrical illusion and the replacement of feelings by reflection, is in sync with political enlightenment and oppositional politics.13) However, Waugh’s view does not do justice to the examples of metagenre discussed thus far. Dr Fell’s lecture on the locked-room murder mystery does not betray a dissatisfaction with the genre. On the contrary, he confesses that he has “been improving his mind with sensational fiction for the last forty years” (emphasis added); and the lecture helps him and his listeners sort out their ideas on the murders they are currently investigating.

Interesting examples of metagenre go far beyond the simple strategy of either opposing or endorsing genre conventions. As pointed out above, they may bring different genres (and different attitudes to these genres) into play. In A Midsummer Night’s Dream, for instance, Shakespeare dismisses satire and parodies tragedy, while simultaneously defining and defending his own brand of comedy. A metageneric statement may also be at odds with what a text does, in the manner of the liar paradox. Like the [→ page 15] Cretan who says that Cretans are liars, a text may repudiate a genre while simultaneously practicing it. The sonnets analysed by Bauer express misgivings about the rigid formal constraints of the sonnet, but they all have fourteen lines and a Petrarchan rhyme scheme. The various explicit and implicit instances of metagenre in a text may also contradict each other, and they may change in the course of a text (as they do in Bauer’s examples, which initially reject but ultimately embrace the sonnet conventions). The most rewarding cases of metagenre create a complex and dynamic debate, a concert of critical and affirmative voices through which a text ultimately achieves a sense of itself. This is also true for the novel analysed in the postscript of this article.

5. Postscript:

The Journey from Comedy to Tragedy in Where Angels Fear to Tread

Forster’s first novel, which was published in 1905, revolves around three journeys from Sawston, a middle-class London suburb, to Monteriano, a small town in Tuscany modelled on San Gimignano. The first of these journeys is undertaken by Lilia Herriton, a young widow who has become an embarrassment to her in-laws after the death of her husband Charles. To prevent her from marrying Mr Kingcroft, whom they consider unsuitable, the Herritons send her to Italy. She is accompanied by Caroline Abbott, an acquaintance who is supposed to watch Lilia and to make sure that she does not disgrace the family. The manœuvre backfires. In Monteriano Lilia becomes engaged to someone even less suitable than Mr Kingcroft; her fiancé, Gino Carella, is a local, much younger than her, and the son of a dentist. The news of this event triggers the second trip, which is taken by Philip Herriton, Charles’s younger brother, who is sent by his mother to break off the engagement. He comes too late, however, as Lilia is already married when he arrives. The third journey is another mission of interference aptly described by the allusion in the title.14) After Lilia has died in giving birth to a son, Caroline lets it be known that she wants to adopt him. For reasons of pride and reputation rather than a genuine interest in the boy, Mrs Herriton decides to adopt him herself. She sends Philip and his sister Harriet [→ page 16] to persuade or bribe Gino to give up the boy. This, however, is the last thing that Gino wants to do because he loves his son deeply. Eventually, Harriet abducts the boy, who dies in a traffic accident outside Monteriano. When Philip tells Gino about the death of his son, Gino almost kills him. They are eventually reconciled by Caroline, who has also come to Monteriano on a parallel trip, and Gino forgives his English relatives and also protects them from any legal consequences of their actions. The novel ends with Philip, Harriet and Caroline travelling back to England empty-handed; the only lasting and tangible result of the three journeys would appear to be a friendship between Philip and Gino.

In a letter written to his friend R. C. Trevelyan soon after the publication of the novel, Forster writes:

The object of the book is the improvement of Philip […]. In ch. 5 he has got into a mess, through trying to live only by a sense of humour and by a sense of the beautiful. The knowledge of the mess embitters him, and this is the improvement’s beginning. From that time I exhibit new pieces of him—pieces that he did not know of, or at all events had never used. He grows large enough to appreciate Miss Abbott, and in the final scene he exceeds her.15)

In presenting Philip as a miscellany of separate pieces, some of them unused, Forster employs the same terms as in other writings about the English middle class. In “Notes on the English Character,” for instance, he argues that, due to self-denial and inhibition, a typical English person is undeveloped and incomplete (10). What follows from this diagnosis is a cure that consists primarily in acknowledging, expressing and integrating the unused pieces of the self. As Forster writes in a letter on Maurice: “My defence at any Last Judgement would be ‘I was trying to connect up and use all the fragments I was born with.’”16) Margaret Schlegel in Howards End thinks along the same lines: “Only connect! That was the whole of her sermon. Only connect the prose and the passion, and both will be exalted, and human love will be seen at its highest. Live in fragments no longer. Only connect, and the beast and the monk, robbed of the isolation that is life to either, will die” (183-84).17)

[→ page 17] In addition to its personal and psychological meaning, Forster’s imperative to connect also has a public and communal meaning. Connecting oneself involves connecting with other people, especially those from whom one is separated by social, political and cultural boundaries. In Howards End, for instance, the characters form relationships across the divisions of the English class system. In A Passage to India, they attempt to do so despite the hierarchies of colonial rule. In Where Angels Fear to Tread, the improvement of Philip, the process of using and connecting the fragments he was born with, is likewise accompanied by connecting with Gino and transcending the barriers between Sawston and Monteriano. This process is, as I have indicated above, linked to a metageneric shift from comedy to tragedy.18) It is this shift that I want to trace in the present reading, doing justice to its complexity and to the aestheticist inflections by which it is complicated. I am particularly interested in a puzzling, seemingly contradictory development in the final chapter that, as far as I can see, has not been adequately explained so far.

Forster describes Philip in a lengthy passage, which comes at a curiously late point, almost halfway through the novel and somewhat like an afterthought. After focusing on Philip’s loneliness as a self-conscious intellectual, it touches upon his sense of beauty and his sense of humour, also mentioned in the letter to Trevelyan.

At all events he had got a sense of beauty and a sense of humour, two most desirable gifts. The sense of beauty developed first. It caused him at the age of twenty to wear parti-coloured ties and a squashy hat, to be late for dinner on account of the sunset, and to catch art from Burne-Jones to Praxiteles. At twenty-two he went to Italy with some cousins, and there he absorbed into one aesthetic whole olive-trees, blue sky, frescoes, country inns, saints, peasants, mosaics, statues, beggars. He came back with the air of a prophet who would either remodel Sawston or reject it. All the energies and enthusiasms of a rather friendless life had passed into the championship of beauty.

In a short time it was over. Nothing had happened either in Sawston or within himself. He had shocked half a dozen people, squabbled with his sister, and bickered with his mother. He concluded that nothing could happen, not knowing that human love and love of truth sometimes conquer where love of beauty fails.

A little disenchanted, a little tired, but aesthetically intact, he resumed his placid life, relying more and more on his second gift, the gift of humour. If he could not [→ page 18] reform the world, he could at all events laugh at it, thus attaining at least an intellectual superiority. Laughter, he read and believed, was a sign of good moral health, and he laughed on contentedly. (54-55)

In describing Philip’s sense of beauty, the passage introduces a third term that we will encounter repeatedly in looking at the shift from the comic to the tragic. Forster enriches his metageneric argument by combining it with a response to the aestheticism of the late nineteenth century. The development from the sense of beauty to the sense of humour should not be taken to mean that the two are opposed to each other. Philip does not give up the first in favour of the second; there is rather a gradual shift in emphasis. Moreover, the two share an important characteristic in that they turn Philip into a spectator, an observer who is not involved in the events around him and takes only an aesthetic pleasure in studying them.19) This attitude is especially evident in his encounters with Caroline. Sometimes he observes her in generally aesthetic terms:

Without being exactly original, she did show a commendable intelligence, and though at times she was gauche and even uncourtly he felt that here was a person whom it might be well to cultivate. (58; emphasis added)

He assented, but her remark had only an aesthetic value. He was not prepared to take it to his heart. (123)

Sometimes in pictorial terms:

For he saw a charming picture, as charming a picture as he had seen for years—the hot red theatre; outside the theatre, towers and dark gates and medieval walls; beyond the walls, olive-trees in the starlight and white winding roads and fireflies and untroubled dust; and here in the middle of it all Miss Abbott, wishing she had not come looking like a guy. She had made the right remark. Most undoubtedly she had made the right remark. This stiff suburban woman was unbending before the shrine. (93-94)

Sometimes in theatrical terms:

After a silence, which he intended to symbolize to her the dropping of a curtain on the scene, he began to talk of other subjects. (20; emphasis added)

[→ page 19] “Now that we [Philip and Caroline] have quarrelled we scarcely want to travel in procession all the way down the hill. Well, goodbye; it’s all over at last; another scene in my pageant has shifted.” (125; emphasis added)

And sometimes in terms of comedy, as in the following passage, in which Caroline is included with others and in which the word humour is used as in comedy of humours, where it refers to predictable, narrow-minded eccentrics that are ruled by a single obsession:

Philip saw no prospect of good, nor of beauty either. But the expedition promised to be highly comic. He was not averse to it any longer; he was simply indifferent to all in it except the humours. These would be wonderful. Harriet, worked by her mother; Mrs Herriton, worked by Miss Abbott; Gino, worked by a cheque—what better entertainment could he desire? There was nothing to distract him this time; his sentimentality had died, so had his anxiety for the family honour. He might be a puppet’s puppet, but he knew exactly the disposition of the strings. (74-75)

As indicated above, Philip’s spectator attitude means that he is not able—and not willing—to become involved in the events around him. He is fully aware of this and justifies his non-involvement with a philosophy that, in a rare moment of confidence, he shares with Caroline during a chance encounter on the train to London. When she tells him that her Italian experiences made her hate the “mediocrity and dullness and spitefulness” (61) of Sawston society, he answers:

“Society is invincible—to a certain degree. But your real life is your own, and nothing can touch it. There is no power on earth that can prevent your criticizing and despising mediocrity—nothing that can stop you retreating into splendour and beauty—into the thoughts and beliefs that make the real life—the real you.” (62)

During a later conversation, which takes place in Santa Deodata, the church of Monteriano, he again affirms his philosophy of non-involvement:

“Miss Abbott, don’t worry over me. Some people are born not to do things. I’m one of them […]. I seem fated to pass through the world without colliding with it or moving it—and I’m sure I can’t tell you whether the fate’s good or evil. I don’t die—I don’t fall in love. And if other people die or fall in love they always do it when I’m not there. You are quite right: life to me is just a spectacle, which—thank [→ page 20] God, and thank Italy, and thank you—is now more beautiful and heartening than it has ever been before.” (120-21)

Philip’s spectator attitude is shown to be an inadequate response to the course of events. It leaves him in “a mess” (149), as Forster writes to Trevelyan. His sense of humour is particularly problematic.20) Philip “always adopted a dry satirical manner when he was puzzled” (59; emphasis added); it would appear that his manner is primarily a defence mechanism. Lilia complains to him, “[Y]ou said funny things about me to show how clever you were!” (27). In other words, Philip cultivates his sense of humour to achieve a feeling of superiority that is unfounded. As Thomas Hobbes points out, the self-elevation of laughter is often a matter of wishful thinking rather than a sign of genuine precedence: “And it [laughter] is incident most to them, that are conscious of the fewest abilities in themselves; who are forced to keep themselves in their own favour, by observing the imperfections of other men. And therefore much Laughter at the defects of others, is a sign of Pusillanimity” (43).

Philip’s sense of humour is also problematic because it prevents him from acknowledging the tragic dimension of the events happening around him. This dimension is evident not only in the deaths of Lilia and her son but also in Lilia’s marriage to Gino, which is presented in tragic terms from the start: “It was in this house [the house that Lilia buys for Gino after their marriage] that the brief and inevitable tragedy of Lilia’s married life took place” (31). Lilia soon learns that married life in Monteriano means the “brotherhood of man” and the “democracy of the caffè” for Gino (36), and something close to solitary confinement at home for her—a worse prison than the respectable existence that the Herritons imposed on her in Sawston. When she discovers that Gino is spending his time away from her not only with male companions at the café but in bed with another woman, she breaks down in despair, realising the hopelessness of her situation. “Lilia had achieved pathos despite herself, for there are some situations in which vulgarity counts no longer. Not Cordelia nor Imogen more deserve our tears” (47). The tragic nature of Lilia’s story is indicated not only by the allusion to King Lear and Cymbeline but also by the concept of pathos, a key [→ page 21] element in Aristotle’s theory of the genre.21) Forster complicates Lilia’s tragedy by acknowledging that it is at odds with her vulgarity, an incongruity that is echoed in the oxymoron “sordid tragedy” (55) later on. This incongruity suggests an interesting parallel between Lilia and Philip. In both cases, there is a considerable resistance to tragedy. While Philip refuses to see the tragic because of his comic prejudices, Lilia is unlikely to experience it because of who she is. With her vulgarity, weakness and foolishness, Lilia belongs in a comedy or satire. But the nature of the events ultimately overrides the nature of the character—“the wisest of women could hardly have suffered more” (47)—and thus Lilia achieves the status of a tragic heroine.22)

The most problematic part of Philip’s philosophy is his embrace of passivity. Caroline is vehemently opposed to it, pointing out that, despite his claims about non-involvement and inaction, he is acting on behalf of others: “Anyone gets hold of you and makes you do what they want. And you see through them and laugh at them—and do it” (120). Philip’s claims are thoroughly disproved by the events around the baby’s death. In the conversation with Caroline that takes place in Santa Deodata, he maintains that he “pass[es] through the world without colliding with it,” but he quite literally collides with it when his coach runs into Caroline’s on the way out of Monteriano. He also states, as quoted above, that he does not die or fall in love, and that he is not present when others do so (see 121). However, Caroline almost immediately tells him that, because of his passivity, he is “dead—dead—dead,” (120) and he does fall in love with Caroline herself. He is present when Gino’s son dies, holding him in his arms, and when Caroline falls in love with Gino, which happens (or reaches the point at which she can no longer resist it) when she reconciles the two men and enfolds Gino in her arms. Moreover, Philip learns in a later conversation with Caroline that he is not only present at her falling in love but also responsible for it. The scene of reconciliation would not have taken place if he had followed Caroline’s advice to bundle Harriet into a coach and leave Monteriano at once (159-60).

The inadequacy of Philip’s spectator attitude is also, and most paradoxically, shown at the place where it would seem to be most appropriate: the theatre. This is where, during their second visit to Monteriano, Philip [→ page 22] and Caroline make a spontaneous decision to go, and they succeed in persuading Harriet to join them, pointing out that the opera they are going to attend, Donizetti’s Lucia di Lammermoor, is based on a novel by Sir Walter Scott (92). On a previous occasion, Philip remembers, he saw La Zia di Carlo at the same theatre, an Italian translation or adaptation of Thomas Brandon’s farcical comedy Charley’s Aunt (93). The two performances represent the shift from comedy to tragedy in Where Angels Fear to Tread, and they also suggest, because of their British origin, that the journey to Italy is a journey of self-discovery for the English visitors. Tua res agitur: What Philip, Caroline and Harriet see on the stage of Monteriano comes from their own country. To return to Philip’s spectator attitude, it proves to be out of place at the performance of Lucia di Lammermoor. Instead of watching and listening from an aesthetic distance, the audience join in the performance, accompanying it “with tappings and drummings, swaying in the melody like corn in the wind,” murmuring “like a hive of happy bees,” greeting the performers and showering the stage with flowers (94-95).23) When a bouquet with a billet-doux lands in Harriet’s lap, Philip grabs it and shouts, “Whose is it?,” making the house explode with laughter (96). He is directed to a box, where he finds himself, to his great surprise, not handing over the bouquet but being pulled up and greeted by Gino. The incident shows Philip turning from a spectator into a participant—albeit without a will of his own as yet. As a messenger of his mother and of unknown Italians writing love letters, his actions and movements are directed by others.

The pivotal moment in Philip’s improvement is when, after the death of Gino’s son, he decides to give up his spectator attitude and accept the responsibility that, so far, he has not acknowledged:

As yet he could scarcely survey the thing. It was too great. Round the Italian baby who had died in the mud there centred deep passions and high hopes. People had been wicked or wrong in the matter; no one save himself had been trivial. Now the baby had gone, but there remained this vast apparatus of pride and pity and love. […]

The course of the moment—that, at all events, was certain. He and no one else must take the news to Gino. It was easy to talk of Harriet’s crime—easy also to blame the negligent Perfetta or Mrs Herriton at home. Everyone had contributed—even Miss Abbott and Irma. If one chose, one might consider the catastrophe composite or the work of fate. But Philip did not so choose. It was his own [→ page 23] fault, due to acknowledged weakness in his own character. Therefore he, and no one else, must take the news of it to Gino. (133-34)

Philip is still a messenger, but a messenger acting on his own accord, not on behalf of others. He also abandons his comic perspective and begins to see the events in tragic terms. The passage invokes key concepts of tragedy: the great or sublime in characters and events, the catastrophe, pity (one of the two principal emotions felt by the audience, according to Aristotle) and the fault (Aristotle’s hamartia, the flaw of the tragic protagonist).24) Earlier on, Philip thought that the people around him behaved like characters in a comedy; now he realises that the comic category of the “trivial” applies only to himself. The message that he now carries to Gino plunges him into the tragic world of suffering. In his first wave of grief at the death of his son, Gino turns against Philip, tortures him and almost kills him—until Caroline arrives on the scene and reconciles the two men.

Philip’s improvement can also be traced in his changing attitude towards Caroline. When he arrives in Monteriano and catches his first glimpse of her approaching the station in a coach, she fully meets his comic prejudices, looking ridiculous while “holding starfish fashion onto anything she could touch” (15). His question how long Lilia has been engaged makes Caroline look “like a perfect fool—a fool in terror” (17). During the ensuing interview on the way from the station to the town, he feels very superior, adopting his “dry satirical manner” and asking questions as if in a cross-examination, while she is giving evasive answers and leaving her sentences unfinished (understandably enough because he does not know that Lilia is already married, and Caroline is afraid to tell him). However, in later conversations he gradually abandons his assumption of superiority and “grows large enough to appreciate Miss Abbott” (149), as Forster writes in his letter to Trevelyan. Occasionally, he still deplores her “usual feminine incapacity for grasping philosophy” (62), but he increasingly realises that Caroline is not the dull and dutiful woman he thought her to be, but a fellow critic of the rigid proprieties of Sawston—and moreover an unpredictable human being whose actions are often surprising. By the end of the novel, he loves her, admires her to the extent of regarding her as a goddess (139, 147), and he loses his capacity (or his pretence) to see through her: [→ page 24] “Why was she so puzzling? He had known so much about her once – what she thought, how she felt, the reasons for her actions. And now he only knew that he loved her, and all the other knowledge seemed passing from him just as he needed it most” (142).

It would appear that the appropriate conclusion of Philip’s improvement is a relationship with Caroline. He has grown mature enough to appreciate her, he has been punished for his faults and failures by Gino, he has decided to take the step from aesthetic observation to involvement and responsibility—does he not deserve the love of the woman who has similarly grown and matured through her experiences in Monteriano? “After all,” Philip thinks, “was the greatest of things possible? Perhaps, after long estrangement, after much tragedy, the South had brought them together in the end” (144). This is roughly what happens in Forster’s other Italian novel, A Room with a View, which concludes with the heterosexual union of two English travellers brought together by their experiences abroad. However, this is not what happens in Where Angels Fear to Tread. Philip’s hopes are disappointed. Caroline fails to return his love, and he seems to relapse into his former, non-involved self. In three crucial passages at the end of the novel, he is again described as a spectator of life. The first focuses on the moment when Caroline reconciles the two men after the baby’s death; Philip is contemplating Caroline and Gino as if they were a painting:

All through the day Miss Abbott had seemed to Philip like a goddess, and more than ever did she seem so now. […] Such eyes he had seen in great pictures but never in a mortal. Her hands were folded round the sufferer, stroking him lightly, for even a goddess can do no more than that. And it seemed fitting, too, that she should bend her head and touch his forehead with her lips.

Philip looked away, as he sometimes looked away from the great pictures where visible forms suddenly become inadequate for the things they have shown to us. He was happy; he was assured that there was greatness in the world. (138-39)

The second passage follows the final and most striking of the many surprises that Caroline has in store for Philip. They are on the train, approaching the St Gotthard Tunnel and thus on the point of leaving the magical soil of Italy. Philip is waiting for a sign that she returns his love but instead she confesses to him that she loves Gino. She then proceeds to ask Philip to laugh at her:

[→ page 25] “Laugh at love?” asked Philip.

“Yes. Pull it to pieces. Tell me I’m a fool or worse—that he’s a cad. Say all you said when Lilia fell in love with him. That’s the help I want. I dare tell you this because I like you—and because you’re without passion; you look on life as a spectacle; you don’t enter it; you only find it funny or beautiful. So I can trust you to cure me. Mr Herriton, isn’t it funny?” (145)

Caroline has evidently been too preoccupied with Gino to recognise any changes in Philip. She still thinks of “Mr Herriton” as a detached connoisseur of the human comedy. The third passage describes Philip’s response to her confession after he has understood all of its implications, in particular his own contribution to her falling in love with Gino:

“But through my fault,” said Philip solemnly, “he is parted from the child he loves. And because my life was in danger you came and saw him and spoke to him again.” For the thing was even greater than she imagined. Nobody but himself would ever see round it now. And to see round it he was standing at an immense distance. He could even be glad that she had once held the beloved in her arms.

[…]Philip’s eyes were fixed on the Campanile of Airolo. But he saw instead the fair myth of Endymion. This woman was a goddess to the end. For her no love could be degrading: she stood outside all degradation. This episode, which she thought so sordid, and which was so tragic for him, remained supremely beautiful. To such a height was he lifted that without regret he could now have told her that he was her worshipper too. (147-48)

Philip has become the kind of observer he formerly aspired to be. He is superior to everybody else—“[n]obody but himself would ever see round it now”—and, instead of feeling the pain of his disappointment, he experiences the situation in aesthetic terms. “[S]tanding at an immense distance,” he views the events as an “episode” and as a literary myth that is “supremely beautiful.” Philip is almost like a reader or critic, who, having arrived at the end of a novel, is in a position to see its “pattern,” i.e. the structure or symmetry of relations that emerges when surveying a plot as a whole.25)

To sum up, Philip’s improvement seems to be arrested and even inverted precisely when it is bound to arrive at its logical conclusion. The final scenes push him back into the very role that is earlier presented as sadly deficient.27) There are, to my mind, three explanations of this inconsistency. [→ page 26] The first could be labelled “poetic justice.” The final meeting between Caroline and Gino, which makes her fall in love with him for good, comes about as a result of Philip’s passivity and negligence. Philip himself is thus responsible for directing Caroline’s feelings towards Gino and for the impossibility of his own relationship with her. His improvement deserves the verdict “too little, too late.” The second explanation takes Forster’s sexual orientation into account. It turns the ending of the novel into a coded statement on homoerotic desire and the difficulties that it was faced with at the beginning of the twentieth century. In this explanation, the various relationships that we see at the end of the novel, both real and imagined, all stand for love between men. That the bond between Philip and Gino remains the only lasting outcome becomes a tacit assertion of this love. That Philip’s relationship with Caroline and hers with Gino are blocked serves as an acknowledgment that a full-scale union—“body and soul,” as Caroline says (147)—with the blessing of society is inconceivable between men.

While both of these explanations can be defended, I would like to make a case for a third, which is based on my metageneric argument and on the shift from comedy to tragedy. This shift also informs Philip’s puzzling relapse at the end of the novel. Admittedly, he returns to his former role as an observer of the spectacle of life, but the nature of the spectacle has changed; it is a tragedy rather than a comedy. When he sees Caroline embracing Gino, her eyes are “full of infinite pity and of majesty,” and Philip is assured that there is “greatness in the world” (139). The key term “great” occurs again in the passage describing his view of her in the final moments of the novel—“the thing was even greater than she imagined” (147)—and we also encounter an echo of Lilia’s “sordid tragedy” in the following sentence about Caroline: “This episode, which she thought so sordid, and which was so tragic for him, remained supremely beautiful” (147-48). Caroline presumably thinks of her love for Gino as “sordid” because of its physical aspect, but to Philip, this aspect does not degrade it in any way, which may be one of the reasons why “in the final scene he exceeds her,” as Forster writes to Trevelyan (149).26)

It is not only the nature of the spectacle that has changed in the final scenes. The spectator and his relation to what he is observing have changed as well. Philip may be “standing at an immense distance” and lifted “to [→ page 27] such a height,” but he is no longer in a position of superiority as both the spectacle and the spectator have been elevated at the same time. Philip now also offers the sympathy that, according to Aristotle, is felt by the audience of a tragedy; the “infinite pity” that he saw in Caroline’s eyes is reflected in his own response to her: “In that terrible discovery Philip managed to think not of himself but of her” (146). Caroline needs someone to talk to about Gino—“if I mayn’t speak about him to you sometimes, I shall die” (146)—and she needs someone to laugh at her, thus helping her to gain some sort of distance to, and control of, her feelings. Thus even the laughter and “the dry satirical manner” that Philip adopts when talking to her about her love for Gino become an expression of his sympathy. Playing the role of the detached observer has paradoxically become a mode of sympathetic involvement.

Bochum

Works Cited

Aristotle. Aristotle: The Poetics. Trans. W. Hamilton Fyfe. Aristotle: The Poetics. “Longinus”: On the Sublime. Demetrius: On Style. Rev. ed. Loeb Classical Library. London: Heinemann, 1960. 1-118.

Austen, Jane. Emma. Ed. Fiona Stafford. Penguin Classics. London: Penguin, 1996.

Bauer, Matthias. “Self-Imposed Fetters: The Productivity of Formal and Thematic Restrictions.” Connotations 27 (2018): 1-18. https://www.connotations.de/article/matthias-bauer-self-imposed-fetters-the-productivity-of-formal-and-thematic-restrictions/. 10 Feb. 2022.

Brecht, Bertolt. “Kleines Organon für das Theater.” Schriften zum Theater: Über eine nicht-aristotelische Dramatik. Frankfurt: Suhrkamp, 1968. 128-73.

Carr, John Dickson. The Hollow Man. London: Orion Books, 2013.

Crews, Frederick C. E. M. Forster: The Perils of Humanism. Princeton: Princeton UP, 1962.

Fishelov, David. Metaphors of Genre. University Park, PA: The Pennsylvania State UP, 1993.

Forster, E. M. Aspects of the Novel. Ed. Oliver Stallybrass. Abinger Edition. London: Edward Arnold, 1974.

Forster, E. M. Howards End. Ed. Oliver Stallybrass. Abinger Edition. London: Edward Arnold, 1973.

Forster, E. M. Maurice. Ed. P. N. Furbank. Penguin Twentieth-Century Classics. London: Penguin, 1972.

Forster, E. M. “Notes on the English Character.” Abinger Harvest. London: Edward Arnold, 1936. 3-14.

Forster, E. M. Where Angels Fear to Tread. Ed. Oliver Stallybrass. Abinger Edition. London: Edward Arnold, 1975.

Fowler, Alastair. Kinds of Literature: An Introduction to the Theory of Genres and Modes. Oxford: Clarendon, 1982.

Fowles, John. The French Lieutenant’s Woman. New York: Back Bay Books, 2010.

Genette, Gérard. Palimpsestes: La littérature au second degré. Paris: Editions du Seuil, 1982.

Giltrow, Janet. “Meta-Genre.” The Rhetoric and Ideology of Genre: Strategies for Stability and Change. Ed. Richard Coe, Lorelei Lingard and Tatiana Teslenko. Cresskill: Hampton, 2002. 187-205.

Harington, Sir John. “An Apology for Ariosto: Poetry, Epic, Morality.” English Renaissance Literary Criticism. Ed. Brian Vickers. Oxford: OUP, 1999. 302-24.

Hauthal, Janine, et al. “Metaisierung in der Literatur und anderen Medien: Begriffsklärungen, Typologien, Funktionspotentiale und Forschungsdesiderate.” Metaisierung in Literatur und anderen Medien: Theoretische Grundlagen—Historische Perspektiven—Metagattungen—Funktionen. Ed. Janine Hauthal et al. Berlin: De Gruyter, 2007. 3-21.

Hauthal, Janine. “Metaization and Self-Reflexivity as Catalysts for Genre Development: Genre Memory and Genre Critique in Novelistic Meta-Genres.” The Cultural Dynamics of Generic Change in Contemporary Fiction: Theoretical Frameworks, Genres and Model Interpretations. Ed. Michael Basseler, Ansgar Nünning and Christine Schwanecke. Trier: WVT, 2013. 81-114.

Hobbes, Thomas. Leviathan. Ed. Richard Tuck. Cambridge: CUP, 1991.

Huang-Tiller, Gillian. “The Modernist Sonnet and the Pre-Postmodern Consciousness: The Question of Meta-Genre in E. E. Cummings’ W [ViVa] (1931).” Spring 14/15 (2005/06): 156-77.

Hutcheon, Linda. A Theory of Parody: The Teachings of Twentieth-Century Art Forms. Urbana: U of Illinois P, 2000.

Jakobson, Roman. “Concluding Statement: Linguistics and Poetics.” Style in Language. Ed. Thomas A. Sebeok. Cambridge: MIT, 1960. 350-77.

Keller Simon, Richard. “E. M. Forster’s Critique of Laughter and the Comic: The First Three Novels as Dialectic.” Twentieth Century Literature 31 (1985): 199-220.

King, Jeannette. Tragedy in the Victorian Novel: Theory and Practice in the Novels of George Eliot, Thomas Hardy and Henry James. Cambridge: CUP, 1978.

Niederhoff, Burkhard. “E. M. Forster and the Supersession of Plot by Leitmotif: A Reading of Aspects of the Novel and Howards End.” Anglia 112 (1994): 341-63.

Niederhoff, Burkhard. Die englische Komödie: Eine Einführung. Berlin: Erich Schmidt, 2014.

Pettit, Alexander. “Comedy and Metacomedy: Eugene O’Neill’s Desire under the Elms and Its Antecedents.” Modern Language Quarterly 78 (2017): 51-76.

Pope, Alexander. “An Essay on Criticism.” The Poems of Alexander Pope. Ed. John Butt. London: Routledge, 1963. 143-68.

Rose, Margaret A. Parody: Ancient, Modern, and Post-Modern. Cambridge: CUP, 1993.

Schäffauer, Markus Klaus. “Gattungspassagen und Metaisierung am Beispiel des Bestiariums.” Metaisierung in Literatur und anderen Medien: Theoretische Grundlagen—Historische Perspektiven—Metagattungen—Funktionen. Ed. Janine Hauthal et al. Berlin: De Gruyter, 2007. 263-81.

Scheffel, Michael. Formen selbstreflexiven Erzählens: Eine Typologie und sechs exemplarische Analysen. Tübingen: Niemeyer, 1997.

Shakespeare, William. A Midsummer Night’s Dream. Ed. Harold F. Brooks. The Arden Shakespeare. London: Methuen, 1979.

Shakespeare, William. Shakespeare’s Sonnets. Ed. Katherine Duncan-Jones. The Arden Shakespeare. London: Methuen, 2010.

Sterne, Laurence. Tristram Shandy. Ed. Howard Anderson. Norton Critical Edition. New York: Norton, 1980.

Stone, Wilfred. The Cave and the Mountain: A Study of E. M. Forster. Stanford: Stanford UP, 1966.

Waugh, Patricia. Metafiction: The Theory and Practice of Self-Conscious Fiction. London: Routledge, 1984.

Wilde, Alan. “The Aesthetic View of Life: Where Angels Fear to Tread.” Modern Fiction Studies 7 (1961): 207-16.

Wolf, Werner. “Formen literarischer Selbstreferenz in der Erzählkunst: Versuch einer Typologie und ein Exkurs zur ‘mise en cadre’ und ‘mise en reflet/série.’” Erzählen und Erzähltheorie im zwanzigsten Jahrhundert: Festschrift für Wilhelm Füger. Ed. Jörg Helbig. Heidelberg: Winter, 2001. 49-84.

Zipfel, Frank. “‘Very Tragical Mirth’: The Play Within the Play as a Strategy for Interweaving Tragedy and Comedy.” The Play Within the Play: The Performance of Meta-Theatre and Self-Reflection. Ed. Gerhard Fischer and Bernhard Greiner. Amsterdam: Rodopi, 2007. 203-20.

Ring out, wild bells, to the wild sky,

Ring out, wild bells, to the wild sky,