“In Another Light”: New Intertexts for David Dabydeen’s “Turner”

Carl Plasa

Published in Connotations Vol. 26 (2016/17)

Abstract

As its “Preface” states, David Dabydeen’s “Turner” (1994) takes its inspiration from Joseph Mallord William Turner’s Slavers Throwing Overboard the Dead and Dying—Typhon Coming On (1840), more commonly known as The Slave Ship. Dabydeen’s reading of Turner’s celebrated painting (and of Ruskin’s famous commentary on it) has been widely debated by critics, but, as this essay demonstrates, “Turner” has an intertextual life that extends far beyond The Slave Ship and the Ruskinian response to it. The essay develops this argument, in the first instance, by showing how Ruskin’s influence on Dabydeen’s poem is traceable not only to his enraptured account of The Slave Ship but also other parts of the chapter, in Modern Painters, vol. 1 (1843), which that account rounds off. As the essay goes on to show, it is not just that these elements of Ruskin’s chapter have been all but overlooked by intertextual analyses of “Turner” but that two other works have been similarly neglected: Shakespeare’s Macbeth (1606) and Toni Morrison’s Beloved (1987). These texts demand our attention as still more significant sources for Dabydeen’s poem and contribute much to a new understanding of its disturbing imaginative vision.

The sea has many voices,

Many gods and many voices.

T. S. Eliot, “The Dry Salvages” (184)

Introduction: Opening the Frame

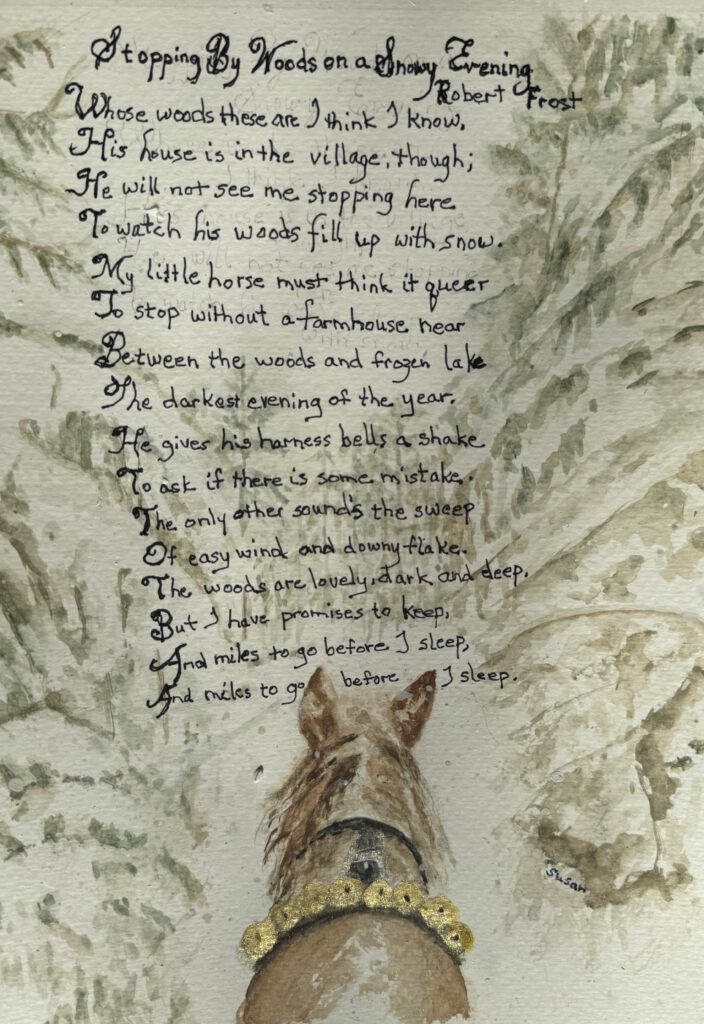

According to its “Preface,” David Dabydeen’s “Turner” (1994) takes its inspiration from a celebrated painting by J. M. W. Turner entitled Slavers Throwing Overboard the Dead and Dying—Typhon Coming On (Figure 1). This canvas, more succinctly known as The Slave Ship, was first exhibited at the Royal Academy in London in 1840 (the same year as the first World Anti-Slavery Convention) and is generally agreed to be based on the Zong massacre (Baucom 268)—one of the most notorious episodes in the history of the transatlantic slave trade. In this incident, which occurred in 1781, 132 sick Africans were jettisoned from the British slave ship, Zong by command of the ship’s captain, Luke Collingwood, in order that their owners could make an insurance claim against their value as cargo lost at sea.1)

While Dabydeen readily appreciates The Slave Ship in aesthetic terms—he calls it Turner’s “finest painting in the sublime style” (Turner ix) and has recently confessed his “love” for the artist and the “epic dimensions” of his art (Pak’s Britannica 187)—he is nonetheless perturbed by what he sees as the undercurrents to Turner’s vision, as [→ page 164] becomes clear from the “Preface”’s last paragraph: “The intensity of Turner’s painting is such,” Dabydeen concludes, that “the artist in private must have savoured the sadism he publicly denounced” (x).2)

Whatever the validity of this startling assertion, the true villain of the piece, in Dabydeen’s eyes, is not so much the possibly perverse artist as his admiring contemporary critic and apologist, John Ruskin, who not only gives a rapturous account of The Slave Ship in the chapter “Of Water, as Painted by Turner” in Modern Painters, vol. I (1843), but also came to own the picture when it was purchased for him by his father in December of the same year, retaining it until it was eventually sold to the American collector, John Taylor Johnston, in 1872. For Dabydeen, the problem with Ruskin’s reading of The Slave Ship is that it emphasizes artistic technique—“dwelling on the genius with which Turner illuminate[s] sea and sky”—at the expense of the painting’s outrageous “subject,” the “shackling and drowning of Africans” (Turner ix) carried out in the name of financial self-interest. As Dabydeen suggests, such a reading is doubly problematic because it effectively renders Ruskin complicit with the actions he ignores: the atrocious historical truth of Turner’s image is relegated to a casual comment in a “brief footnote” in Ruskin’s text, which, as Dabydeen rather ingeniously points out, seems “like an afterthought, something tossed overboard” (Turner ix).

As if to mimic Ruskin’s marginalizing gesture, Dabydeen ejects from his “Preface” the throwaway remark the footnote contains (“She is a slaver, throwing her slaves overboard. The near sea is encumbered with corpses” [Ruskin 572]), before proceeding in the poem proper to render slavery central by salvaging “the submerged head of the African in the foreground of Turner’s painting” (Turner ix) and magically reawakening it to speak the text’s twenty-five Cantos. At the same time, he complicates the picture, so to speak, by introducing into his poem another resurrected castaway, in the form of a “stillborn child tossed overboard from a future ship” (Turner x). Like the slave-captain who condemns the poem’s speaker to his watery fate, this miscreated figure is also named Turner, its role as all-but-silent [→ page 165] auditor to the speaker’s lengthy reverie making the text a kind of dramatic monologue.

Whether or not we accept Dabydeen’s account of Ruskin’s account of The Slave Ship, the larger point is that his engagement with his Victorian precursors alerts us to the importance of the role of intertextual dialogue in “Turner.”3) For most critics, this dialogue rarely extends beyond the poem’s relationship to Turner’s painting, on the one hand, and Ruskin’s reading of it, on the other, and there have been numerous insightful analyses of the text along these lines.13) As this essay argues, however, to position Dabydeen’s poem solely within this particular frame of reference is ultimately reductive, missing the ways in which “Turner” draws on other materials that are just as important to the shaping of its compelling if disturbing imaginative vision.

In order to make this case, the essay is divided into three sections. The first shifts the focus from Ruskin’s critically privileged set-piece reading of The Slave Ship to earlier parts of the chapter and explores their role in “Turner.” It goes on from this, in its second and third sections, respectively, to more extended examinations of “Turner”’s links with two further works—William Shakespeare’s Macbeth (1606) and Toni Morrison’s Beloved (1987)—neither of which has to date received anything more than the most fleeting critical attention as intertexts for Dabydeen’s poem.4)

By excavating Macbeth’s unacknowledged presence in “Turner,” the essay both tells us something new about how Dabydeen imagines the atrocity aboard the Zong and brings out, more broadly, the distinctiveness of his project, since, in so many writings of the Middle Passage—from Robert Hayden and Edward Kamau Brathwaite to George Lamming and Barry Unsworth—it is The Tempest that is invariably the dominant Shakespearean intertext that is invoked and reworked.14) By bringing Beloved’s intertextual role to light, the essay at the same time helps us appreciate “Turner” not just as an example of the empire writing back to the metropolitan centre (whether Turner, Ruskin, Shakespeare or a combination of all three), but also as a text that overruns the borders of the Anglophone Caribbean literary tradition [→ page 166] in which it is located and that operates, instead, according to the intercultural logic of what Paul Gilroy, writing at the same moment as Dabydeen, was to call the Black Atlantic.

The Role of Ruskin

What Dabydeen construes as Ruskin’s insouciance towards the bodies drowning in The Slave Ship has its correlate in the Victorian art critic’s comments on two other of Turner’s productions, the 1835 “vignette to ‘Lycidas’” (Ruskin 566) and Hero and Leander (1837), a picture on which Dabydeen’s poem draws in Cantos XII to XIV. While both of these paintings are responses to narratives in which drowning plays a central part, Ruskin approaches them, once again, primarily in terms of technique, resolutely evaluating the degree to which Turner’s art is able (and occasionally unable) to reproduce particular watery effects. Just before embarking upon the reading of The Slave Ship, Ruskin likens “hold[ing] by a mast or a rock” in order to witness a storm at sea at close quarters to “a prolonged endurance of drowning which few people have courage to go through” (571). Yet, as his chapter suggests, such an experience is one that he is keen to avoid even in the second-hand context of pictorial representation.

Equally, though, the “endurance of drowning,” or some kind of perilous watery submersion, at least, is something to which Ruskin is strangely attracted, especially in his chapter’s opening sections. This is evident, in the first instance, in his observations on the difficulties that artists inferior to Turner have in “giv[ing] a full impression of surface” to “smooth water”: “If no reflection be given, a ripple being supposed,” Ruskin writes, “the water looks like lead,” whereas, “if reflection [is] given, [the water], in nine cases out of ten, looks morbidly clear and deep, so that we always go down into it, even when the artist most wishes us to glide over it” (537; italics in original). This sense of falling into the water rather than skimming across it is also an effect produced by the work of artists who fail to grasp the principle that the reflection of objects (Ruskin’s example is “leaves hanging [→ page 167] over a stream”; 542) is not “an exact copy of the parts of them which we see above the water, but a totally different view and arrangement” (542). By naively “giving underneath a mere duplicate of what is seen above,” Ruskin observes, such artists “are apt to destroy the essence and substance of water, and to drop us through it” (542). Needless to say, such errors and the hazards they offer potential viewers are avoided by the “master mind of Turner” (544), whose technique is so exquisite and secure it not only delights but also protects the critic. Commenting on the water in Turner’s Schloss Rosenau or “Château of Prince Albert” (1841), as he calls it, Ruskin states: “we are not allowed to tumble into it, and gasp for breath as we go down, we are kept upon the surface, though that surface is flashing and radiant with every hue of cloud, and sun, and sky, and foliage” (539).

Ruskin’s comments on reflection are not confined within the frame of art but extend to include the natural realm the artist strives to capture, together with the organization of the eye as it switches focus between different objects. As Ruskin notes, it is this organization that is constitutive of perception and determines how things are either seen or not seen, a point he explains and illustrates, in the chapter’s very first paragraph, by taking the reader turned beholder “to the edge of a pond in a perfectly calm day, at some place where there is duckweed floating on the surface, not thick, but a leaf here and there” (537). On this dreary brink, he tells us:

You will […] see the delicate leaves of the duckweed with perfect clearness, and in vivid green; but, while you do so, you will be able to perceive nothing of the reflections in the very water on which they float, nothing but a vague flashing and melting of light and dark hues, without form or meaning, which to investigate, or find out what they mean or are, you must quit your hold of the duckweed, and plunge down. (538)

With the insistence that the reader-spectator relinquish his or her visual grip on the “duckweed” and “plunge down” in order to “perceive [...] reflections,” Ruskin’s optical experiment here echoes the subaquatic language informing his treatment of such natural phenomena as they appear in the context of art.

[→ page 168] By the end of the chapter, Ruskin has moved a long way off from this tranquil if potentially threatening rural site and into the stormy and corpse-laden Atlantic of The Slave Ship, from which Dabydeen rescues and reanimates his poem’s speaker. Yet, Ruskin’s pond nonetheless resurfaces on several occasions in the course of “Turner,” where it is transformed into one of the principal elements out of which the speaker’s evocation of his African boyhood is forged. The first instance of this occurs at the beginning of Canto II, where the often neologizing speaker compares the impromptu watery descent of the “Stillborn” that he witnesses in Canto I to the event of “a brumplak seed that bursts buckshot / From its pod” (II.2-3) and “fall[s] into the pond / In the backdam of [his] mother’s house” (II.3-4). Just as “pond” dehisces from “pod,” so this initial scene is developed and expanded in Canto III. Here the dangerous if merely metaphorical immersions of the Ruskinian spectator become actively literalized by the speaker’s more daring exploits in a “pond” all his own:

When I strip,

Mount the tree and dive I hit my head

On a stone waiting at the bottom of the pond.

I come up dazed, I float half-dead, I bleed

For days afterwards. (III.16-20)

Like the “savannah” (III.15) that “climb[s] and plunge[s] all day” (III.16), the memory described in these lines is built around the youthful delights of a repetition that seems unending—“Diving from a branch into water, swimming / About, climbing again for another go” (III.13-14)—but that is suddenly stopped. Yet even as the carefree rhythm of “Mount[ing]” and “div[ing]” comes abruptly to an end, the memory of its curtailment lingers on—like the bleeding that continues “For days afterwards” (III.20). It recurs, for instance, in Canto XII, when the speaker “drag[s] [him]self / To the bank of the pond” (XII.24-25) and it is his head that is this time imagined as a bloody “pool / And fountain” (XII.25-26). Or again, there is the example of Canto XVIII, when the “waves slapping [the] face” (XVIII.19) of the [→ page 169] stillborn reawaken the speaker’s recollection of his own “mother’s hands summoning [him] back / To [him]self, at the edge of the pond” (XVIII.20-21), a phrase that simultaneously involves a summoning back of Ruskin.

Intertextual ripples of Ruskin’s pond are discernible not only in the African landscape the speaker describes but also in the complementary English landscape that appears in Canto XVI and that he can only surmise, basing his “knowledge” (XVI.4) on the “Pictures” (XVI.8) adorning the wooden wall of Turner’s cabin as his “ship / Plunge[s] towards another world we never reached” (XVI.4-5). In his comments about the “water […] in the foreground” to the Schloss Rosenau, Ruskin describes the sensation of “glid[ing] over it a quarter of a mile into the picture before we know where we are” (539), and a similar sense of dislocation, in which spectator becomes participant, characterizes the speaker’s encounters with these wall paintings, as he migrates into the shifting scenes he beholds of village life as lived in Turner’s “country” (XVI.9). As these scenes take shape, it soon becomes evident that, like Ruskin’s text, they too raise questions about visibility and invisibility—what, or rather who, can and cannot be seen—while at the same time giving these issues a distinctly racial slant:

I walk along a path shaded

By beech; curved branches form a canopy, protect

Me from the stare of men with fat hands

Feeling my weight, prying in my mouth,

Bidding. The earth is soft here, glazed with leaves,

The path ends at a brook stippled with waterflies,

But no reflection when I gaze into it,

The water will not see me. (XVI.18-25)

As he pursues his imaginary “path,” Dabydeen’s mental traveller is at first not only an unseen figure sheltered and “shaded” by a “canopy” of “curved branches” but also one who enjoys such womb-like enclosure and concealment because it defends him against the commoditizing (and covertly sexual) “stare” of the white “men” who are attracted to him and might like him to do their “Bidding.” Yet, at the point where the path “ends,” the speaker’s invisibility becomes less boon [→ page 170] than burden. In the case of Ruskin’s pond, the absence of reflection the spectator experiences can be resolved in the blink of an eye, but in Dabydeen’s “brook” the situation is different: such absence is less an ephemeral perceptual effect than a trope for the constitutive failure of the white gaze to recognize the black subject in anything other than stereotypical terms.

This figurative blindness is subsequently replicated en masse by the “villagers” (XVI.25) among whom the speaker wanders and, in particular, an old woman “with silver / Hair” (XVI.29-30) who, in contrast to the corpulent-handed male bidders, does not so much stare at the speaker as “through” (XVI.33) him. It is even to be seen in the window of the “butcher’s shop” (XVI.27) that will not countenance the speaker’s own visage, replacing it with the gruesomely suspended carcasses of “goose and pheasant” (XVI.27), while radiantly welcoming “other faces” (XVI.29). This sense of how the visual field accommodates the white subject but excludes the black is climactically underscored when the speaker enters the villagers’ place of worship and finds himself in the presence of another butchered and hanging body. Although the body in question here is that of the crucified Christ, it is mistaken by him as belonging to a less exalted master. As the speaker puts it, what he “behold[s]” on entering the local church and becoming “accustomed” to its melancholy “gloom” (XVI.38) is not God’s Son but the hallucinatory figure of the slave-ship captain who has cast him seaward:

Turner nailed to a tree, naked for all to see,

His back broken and splayed like the spine

Of his own book, blood leaking like leaves

From his arms and waist. (XVI.39-42)

Such hallucinatory misrecognition is perhaps appropriate, given the speaker’s struggle for acknowledgement among the local populace—“The elders and the young” alike (XVI.36)—with his own sense of invisibility and forsakenness paralleled in the disappearance of Christ’s image beneath Turner’s. It can also perhaps be read as wish-fulfilment, despite the “cry” (XVI.43) of “pity and surprise” (XVI.44) [→ page 171] that the hallucination induces, as Turner suffers amid the church’s obscurity in reprisal for the unseen horrors endured by the “grown-ups [who] cried in the darkness” of his “hold” (XVI.6).

As previously observed, Ruskin’s most direct acknowledgement of such horrors in his description of The Slave Ship is confined to a vague footnote, yet Ruskin finesses his own insight even at that safe remove, primarily by transferring the responsibility for the slaves’ sufferings from the human to the inanimate. After all, in his anthropomorphizing phrase, it is the feminized “slaver” itself (or herself) rather than the male master or slave-captain that appears both to own the slaves and to engage in the act of jettison: to recall Ruskin’s insouciant phrase, “She is a slaver, throwing her slaves overboard.”

These evasive rhetorical tactics are evident not only in the footnote that so exercises Dabydeen but also in the main body of Ruskin’s account, where they take the form, coincidentally, of the pathetic fallacy, an aesthetic category Ruskin himself introduced into circulation and analysed in Modern Painters, vol. III (1856). At the climax to his appreciation of Turner’s “canvas,” Ruskin writes in Modern Painters, vol. I (1843):

Purple and blue, the lurid shadows of the hollow breakers are cast upon the mist of night, which gathers cold and low, advancing like the shadow of death upon the guilty ship as it labours amidst the lightening [sic] of the sea, its thin masts written upon the sky in lines of blood, girded with condemnation in that fearful hue which signs the sky with horror, and mixes its flaming flood with the sunlight, and, cast far along the desolate heave of the sepulchral waves, incarnadines the multitudinous sea. (572)

In this powerful ekphrasis, the guilt in question is guilt on the move, as Ruskin ascribes it to the “labour[ing]” vessel rather than captain and/or crew, just as it is the “ship”’s “thin masts” that are “girded with condemnation.”

Such guilt would be merited well enough in the general run of things but assumes additional intensity when it is remembered that the specific historical incident to which Turner’s painting looks back [→ page 172] is that of the Zong atrocity, in which, as the abolitionist campaigner Granville Sharp remarks, “132 innocent human Persons” were subjected to “Wilful Murder” (Lyall 301). Yet, just as Ruskin only admits to the guilt entailed in the slave trade (and this episode particularly) by displacing it from human to non-human, so he admits to its murderous nature only through the detour of allusion, drawing his blood-red deeps from Shakespeare’s Macbeth, a play in which guilt and murder interlock. As the self-questioning Macbeth soliloquizes:

Clean from my hand? No—this my hand will rather

The multitudinous seas incarnadine,

Making the green one red. (2.2.59-62)

In this anxious moment, the links between guilt and murder that Ruskin does not explicitly articulate become overt, along with the limitations they impose upon Macbeth’s destructive powers. He may be able to commit multiple murders (when he speaks these lines he has already just dispatched King Duncan and in so doing also “murder[ed]” the “innocent sleep” [2.2.36]), but what he cannot destroy is the torturing sense of the sinfulness of his actions (even as he will go on to perpetrate further murders). As the lines conclude, Macbeth’s vocabulary changes dramatically from the polysyllabic Latinate phrase in which Ruskin revels—“multitudinous seas incarnadine”—to the monosyllabic English of “green one red.” Yet, Macbeth’s own homicidal trajectory swiftly takes him in the opposite direction, carving out a course from a single initial murder to a profusion of subsequent killings.

As Marcus Wood has shown in some detail, the intertextual “dialogue” between Ruskin’s description of The Slave Ship and Macbeth extends far beyond the borrowing of a single phrase and “runs deep” (65). Equally, though (and this is not something Wood addresses), there is an even profounder dialogue between Shakespeare’s text and Dabydeen’s, as the next section of this essay will show. [→ page 173]

From Ruskin to Macbeth

One of the ways in which such a dialogue is manifest is in terms of the language of cleansing and staining that marks the passage from Shakespeare’s play just cited. The first signs of the presence of that language emerge in the poem in the context of the speaker’s account of his pastoral childhood in Africa. In Canto II, for instance, he recalls how “each morning” (II.34) he and his two sisters “Brush [their] teeth clean” (II.35) with “twigs” (II.34) from the “chaltee tree” (II.33) and then weave games around one of the family cows that involve “decorat[ing] its heels with the blue and yellow / Bark of hemlik” (II.40-41). While this aestheticizing mischief is forbidden by the speaker’s less than playful father, who sends the children “off to school” (II.44), the latter himself observes a different set of daily rituals that nonetheless run along similar lines, as illustrated in Canto IV. Here the father prays at “Dawntime” (IV.14) and “Washe[s] his fingers” (IV.15), “tongue” and “face” (IV.16), “in a sacred bowl / Repeatedly” (IV.15-16), before “smear[ing] / His forehead with green dye” (IV.16-17) and setting out for the “savannah” (IV.18). Such rituals, in turn, parallel those carried out by the enigmatic village elder and “magician” (II.45), Manu, though, in this case, they are connected not so much to prayer as divination. In Canto XVII, for example, Manu “darts his hands out” (XVII.12) at the “ancient ingredients” (XVII.8) in one of the “sacred bowls” (XVII.9) arranged around him, “Scoops up red jelly, daubs it on his face [and] / Howls” (XVII.13-14) before the future visions of white violence and black counter-violence that are opened up to him.

Perhaps the most striking manifestation of this pattern occurs in an incident in Canto III, in which it is the speaker’s own hand rather than that of his father or Manu that becomes central. This time, however, the hand engages in a deed neither prayerful nor prophetic but innocently (and humorously) transgressive:

I dream to be small again, even though

My mother caught me with my fingers

In a panoose jar, and whilst I licked them clean

And reached for more, she came upon me,

[→ page 174] Put one load of licks with a tamarind

Stick on my back, boxed my ears; the jar fell,

Broke, panoose dripped thickly to the floor. (III.1-7)

Even though the memory recalled at this point is a painful one, its sweetness makes it just as difficult to resist as the contents of the “jar” themselves. Given its trivial nature, the self-indulgent crime the speaker commits here is hardly comparable to the macrocosmic evil unleashed by Macbeth, yet Dabydeen’s image of manual transgression is not without a residual Shakespearean flavour, faintly recalling Macbeth’s description of how the play’s increasingly embattled protagonist “feel[s] / His secret murders sticking on his hands” (5.2.16-17). The image further links “Turner” to Macbeth in terms of the irony intrinsic to the speaker’s decision to clean his fingers by licking them. While this action rids those fingers of both the syrup for which they reach and (by implication) whatever guilt this induces, it does so in a way that merely compounds the crime, since it reproduces the oral gratification the speaker is seeking in the first place. The suggestion is that the speaker’s own self-cleansing exercises bear the traces of the very misdemeanour they should eradicate, just as Shakespeare’s “multitudinous seas” are turned red by the very hand Macbeth hopes they will purify. The sense of a sin whose extirpation is not straightforward is captured both by Dabydeen’s use of assonance (the quadruple “ick”-sound stretched across five lines) and the ways in which the punishment the speaker’s mother inflicts on him only works as a reminder of the clinging pleasures of his original offence (“load of licks” and even “Stick”).

These processes of cleansing and staining are not restricted to the scenes of childhood the speaker delineates but feature significantly in the account he gives of his Atlantic experience, where they take on a more sinister dimension and are organized differently depending on race and performed by the sea itself. As becomes evident, the speaker’s posthumous ordeals amid the “endless wash and lap / Of waves” (II.25-26) bring him into contact with other dead figures besides the stillborn child, including the women who are “spew[ed] off the [→ page 175] edges” (IV.26) of the “different sunken ships” (IV.33) he witnesses in the course of his surreal aquatic trials. Although these temporary “companions” (IV.28) are white, he boldly reimagines them as black and blesses them with seductive African names—“Adra, Zentu, Danjera” (V.2)—in order to make them seem more “familiar” (V.1), even as the sea conducts its own unpredictable programme of transformations: it lovingly “decorates” (V.10) the women’s countenances with “festive masks” made of “salt crystals” (V.8) before it “strips them clean” (V.12) of “flesh” (V.9) completely. The sea carries out a similar divestiture of the white male figures of Canto XIV, as it not only “soothes and erases pain from the faces / Of drowned sailors” (XIV.18-19) with “an undertaker’s / Touch” (XIV.17-18) but also liberates them entirely from their bodies and the rough histories inscribed upon them, “unpast[ing] flesh from bone / With all its scars, boils, stubble, marks / Of debauchery” (XIV.19-21).

When it comes to black bodies, however, the sea’s cleansing work is both less extreme and less certain, as suggested by the self-contradictory utterances in Canto IX:

the child

Floats towards me, bloodied at first, but the sea

Will cleanse it. It has bleached me too of colour,

Painted me gaudy, dabs of ebony,

An arabesque of blues and vermilions. (IX.13-17)

Here it is difficult to have confidence in the redemptive future the speaker envisages for the “bloodied” child—the utopian possibility of a clean break with the past, as it were—because of his own history, in which the sea “bleache[s]” his skin only so that it can make it into a kind of tabula rasa or blank canvas on which it “Paint[s]” its “gaudy” hues, restoring the tell-tale “dabs of ebony” which, he claims, it has removed.

Ultimately, the issue of whether the speaker’s skin is bleached or colourfully painted is irrelevant, since the dilemma he confronts goes deeper than this. Dabydeen makes this point in his “Preface,” where, in a prefiguring of the contradictions just noted, he observes how, [→ page 176] despite the sea’s best efforts at whitening the black body, the speaker “still recognizes himself as ‘nigger’” (x)—sees himself, that is, in terms of the degrading stereotypes to which blackness has been historically reduced. As the “Preface” also points out, the catalyst to this recognition is the child, who exposes the speaker’s “desire to begin anew in the sea” (ix) as a forlorn hope and thwarts his “creative amnesia” with the indelible stains of “grievous memory” (x):

‘Nigger!’ it cried, seeing

Through the sea’s disguise as only children can,

Recognising me below my skin long since

Washed clean of the colour of sin, scab, smudge,

Pestilence, death, rats that carry plague,

Darkness such as blots the sky when locusts swarm. (XI.17-22)

As the speaker responds to this brutal address, echoed at four further junctures in the poem (twice in Canto XVIII and twice again in Canto XXV), he returns us to Macbeth and the problem of the aftermath to Duncan’s killing.5) In Shakespeare’s tragedy, the royal blood that stains the hands of the murderous double-act at the play’s centre can be physically removed but comes back to haunt them in the hallucinatory shape of “thick-coming fancies” (5.3.37) that cannot be staunched any more than a “rooted sorrow” can be “Pluck[ed] from the memory” (5.3.40) or the “written troubles of the brain” “Raze[d] out” (5.3.41). In “Turner,” similarly, the speaker’s body can be “Washed clean” of its blackness but he himself cannot escape the radically demeaning associations with which it is encrusted and that are here couched in an overtly Biblical and increasingly apocalyptic language, ranging from “sin, scab [and] smudge” to a “Darkness” that, in another staining metaphor, “blots the sky when locusts swarm” (XI.20-22).

Macbeth’s decision to kill Duncan is partly motivated by a desire to take his place as King but also by a need to reaffirm his own masculinity. This is so particularly in relation to his wife, who fears that he is “too full o’th’ milk of human kindness” (1.5.16) to realize his ambitions and taunts him with the opinion that his initial determination to [→ page 177] “proceed no further in this business” (1.7.31) is unmanly. While such goading prompts Macbeth to tell his “dearest partner of greatness” (1.5.10) that he “dare do all that may become a man” (1.7.46), her own involvement in their destructive enterprise is predicated, ironically, on the very sort of gender-betrayal of which she accuses him, as exemplified when she commands the “spirits / That tend on mortal thoughts” (1.5.39-40) to “unsex” (1.5.40) her and “Come to [her] woman’s breasts / And take [her] milk for gall” (1.5.46-47).

Such gender-instability, in which the wavering Macbeth is “quite unmanned” (3.4.74) and his more resolute spouse defeminized, is consonant with the ontological and linguistic ambiguities of Macbeth as a whole, where “nothing is / But what is not” (1.3.142-43), the dead seem (in the shape of Banquo) to “rise again” (3.4.81) to unnerve the living and the play’s corps of witches, particularly the self-proclaimed three “Weïrd Sisters” (1.3.32), “palter with us in a double sense” (5.7.50). This feature of Macbeth is paralleled in “Turner,” where, to come back to the “Preface,” the “sea […] transform[s]” the poem’s speaker and “complicate[s] his sense of gender” to such an extent that he wishes to “mother” (x) the “piece of ragged flesh” (XI.12) that drifts towards him.6) Yet the speaker is not the only male mother in Dabydeen’s poem, the other being the slave-ship captain, Turner, and it is by reading the vicissitudes of this strange (and ultimately monstrous) figure in the light of Macbeth that it is possible to discern further signs of Dabydeen’s intertextual debt to Shakespeare.

In Shakespeare’s play, Lady Macbeth is prepared not just to be unsexed in pursuit of her goals, but, as the disturbing image of breastmilk turned to gall implies, even to violate maternal duties. Nowhere does this become clearer than in the still more unsettling vision she invokes early on in the play in order to convince her husband of the depth of her resolve:

I have given suck, and know

How tender ’tis to love the babe that milks me;

I would, while it was smiling in my face,

Have plucked my nipple from his boneless gums

[→ page 178] And dashed the brains out, had I so sworn

As you have done to this. (1.7.54-59)

This shocking volte-face has its correlate in the equally volatile maternal disposition of Turner. As the speaker recollects, in one of his earliest flashbacks, this androgynous personage seems at first improbably benign and bountiful, as evidenced in the moment of the departure from Africa etched in Canto IV:

His blue eyes smile at children

As he gives us sweets and a ladle from a barrel

Of shada juice. Five of us hold his hand,

Each takes a finger, like jenti cubs

Clinging to their mother’s teats, as he leads us

To the ship. (IV.34-39)

Here Turner provides the “children” he is in fact enslaving with oral gratification in the form of “sweets” and “shada juice,” offering them the “fingers” of a “hand” they grasp as eagerly as “jenti cubs / Clinging to their mother’s teats.” Yet once his ship is underway, Turner’s features alter dramatically: his “smile” (VIII.4) shrinks “like a worm’s / Sudden contraction” (VIII.4-5) in Canto VIII and “strange words [are] spat” (VIII.5) from the “gentle face” (VIII.6) that had once “so often kissed [...] / His favoured boys” (VII.6-7). By Canto XIV, Turner’s transformation from tenderness to cruelty is complete, as he severs the bond with the speaker with a similarly high-handed violence to that with which Lady Macbeth sunders her ties to her trusting “babe.” At this point, Turner’s fingers are mysteriously devoid of maternal comfort, irrevocably tensed instead into a “hand gripping [the speaker’s] neck, / Pushing [him] towards the [ship’s] edge” (XIV.2-3) and finally letting him “fall towards the sea” (XIV.5). If Turner’s maternal mutability is comparable to that of Lady Macbeth, it is also suggestive of his resemblance to Macbeth’s witches: as Macbeth understands at the end of the play, these “juggling fiends” (5.7.49) are not to be relied upon (they “keep the word of promise to our ear / And break it to our hope” [5.7.51-52]), just as Turner [→ page 179] “curl[s]” the speaker “warmly to his bed” (VIII.9) only to submit him, finally, to “the waters” (XIV.6) and the “flush / Of betrayal” (XIV.7-8).

Macbeth’s realization of the witches’ unreliability emerges specifically in relation to the various predictions about his future that they make, and it is these that provide one final link between Shakespeare’s play and Dabydeen’s poem. For all its preoccupation with the past, “Turner” is, like Macbeth, itself a text with an eye trained on the future, articulating such concerns, as already suggested above, chiefly through the figure of Manu, who routinely holds “daedal / Seed[s] […] up to the sky / For portents of flood [or] famine” (XVIII.22-24) and is able to foresee both Turner’s advent and the “lamentation in the land” (XVII.19) that it will bring. But as well as broadly echoing Macbeth in this way, “Turner” engages with the prophecies in Shakespeare’s play in a more detailed manner by weaving them into its own narrative. This can be seen on at least two occasions, the first of which is in the poem’s dramatic opening Canto, where the speaker reprises the marred origins of the child he comes to adopt:

Stillborn from all the signs. First a woman sobs

Above the creak of timbers and the cleaving

Of the sea, sobs from the depths of true

Hurt and grief, as you will never hear

But from woman giving birth, belly

Blown and flapping loose and torn like sails,

Rough sailors’ hands jerking and tugging

At ropes of veins, to no avail. Blood vessels

Burst asunder, all below-deck are drowned.

Afterwards, stillness, but for the murmuring

Of women. The ship, anchored in compassion

And for profit’s sake (what well-bred captain

Can resist the call of his helpless

Concubine, or the prospect of a natural

Increase in cargo?), sets sail again,

The part-born, sometimes with its mother,

Tossed overboard. (I.1-17)

[→ page 180] Here the child’s abortive condition is underscored both by the truncated first sentence (made all the more jarring by the poem’s far more usual pattern of fluid enjambment) and the way in which the Canto as a whole closes back on itself, recalling its first word in its last, “Stillborn” in “dead” (I.25). Such permanent immobility contrasts sharply with the slaver’s more temporary “stillness,” enacted in the parenthesis that encloses the “well-bred captain” and his Siren-like if “helpless / Concubine” and briefly suspends the poem’s narrative movement—before, that is, like the “anchored” “ship” itself, the verse “sets sail again.”

Considered simply in terms of content, “Turner”’s own imaginative parturition is indeed a moment of “cleaving,” as mother and child are separated from one another by the twinned agonies of labour and death. Approached from a Shakespearean perspective, however, the opening entails cleaving in the directly opposite sense of the word, as the poem once again latches itself onto Macbeth and, in particular, the prophecy spoken by the “Apparition” of a “bloody child” (4.1.90; stage direction) that “none of woman born / Shall harm Macbeth” (4.1.94-95). While such a statement causes Macbeth to assume that he is physically invulnerable and “bear[s] a charmèd life” (5.7.42) during his final confrontation with Macduff, the security it gives him turns out to be false when Macduff discloses that he is the mature embodiment of such a seemingly impossible progeny. As he tells Macbeth, he himself “was from his mother’s womb / Untimely ripped” (5.7.45-46), a condition that connects him, intertextually at least, to Dabydeen’s “part-born,” torn in turn from its mother’s “belly,” albeit “to no avail,” by “Rough sailors’ hands.”

The appearance of Macbeth’s equivocal ghost-child is followed by that of another spirit, in the form of “a child crowned, with a tree in his hand” (4.1.100; stage direction), who states that Macbeth will “never vanquished be, until / Great Birnam Wood to high Dunsinan [sic] Hill / Shall come against him” (4.1.107-09). Such a prophecy once again seems to bode well, since, as its hearer reasons, it is surely not possible either to “impress the forest” (4.1.110) or “bid the tree / Unfix his earthbound root” (4.1.110-11) and advance towards his stronghold. [→ page 181] Like the previous vision of the bloody child, however, the spectre of its tree-bearing counterpart also proves, in the end, to be untrustworthy: Birnam does indeed in a sense become mobile when its branches and foliage are deployed by the forces opposed to the “abhorrèd tyrant” (5.7.10) as a means of camouflaging their march in his direction. Yet the route of this “moving grove” (5.5.38) does not end when Malcolm arrives at Dunsinan and instructs his men to “throw down” their “leafy screens” (5.6.1), but extends into Dabydeen’s poem and the pictures of Turner’s England into which the speaker transports himself in fantasy. Here it is not only that, as noted earlier, the speaker imagines “walk[ing] along a path shaded / By beech” (XVI.18-19)—and in this way enjoys his own version of those Shakespearean “screens”—but that the surrounding bushes and trees are themselves imbued with motion:

[Turner] held a lamp

Up to his country, which I never saw,

In spite of his promises, but in images

Of hedgerows that stalked the edge of fields,

Briars, vines, gouts of wild flowers; England’s

Robe unfurled, prodigal of ornament,

Victorious in spectacle, like the oaks

That stride across the land, gnarled in battle

With storms, lightning, beasts that claw and burrow

In their trunks. (XVI.8-17)

As well as celebrating the beauties of the English countryside, these lines offer an implicit homage to the nation’s naval preeminence (which includes its role in the slave trade) and in doing so are pervaded by a subtle irony. The “oaks / That stride across the land” may seem, like the “stalk[ing]” “hedgerows,” to be “Victorious in spectacle” and to have won the “battle” against the natural world, but ultimately will be cut down to provide the “timbers” for the ship in which their own “images” are in fact displayed. In this respect, they share the predicament of the seemingly untouchable Macbeth himself, defiantly “Hang[ing] out [his] banners” on his castle’s “outward walls” (5.5.1) just moments before the announcement of Lady [→ page 182] Macbeth’s death reduces life to “a tale / Told by an idiot” (5.5.26-27), and he thereafter receives the messenger’s seemingly equally crazed and certainly ominous “report” (5.5.31) that Birnam is on the “move” (5.5.35).

As this section of the essay indicates, Macbeth is just as important an element in “Turner” as the Ruskinian material examined previously (and indeed Turner’s The Slave Ship). Yet, Dabydeen’s poem is imaginatively reliant also on Beloved and it is to this novel—another great contemporary meditation on slavery and the Middle Passage—that the essay’s third and final section is devoted.

African American Connections: “Turner” and Beloved

The relationship between “Turner” and Beloved is evident in numerous respects, the first of which concerns the manner in which each text sets out to retell the story of slavery from the slave’s perspective. In the case of Morrison’s novel, the story she rewrites appears in an 1856 newspaper article by the Reverend P. S. Bassett and revolves around the figure of Margaret Garner, a fugitive slave who, the preceding January, had cut the throat of her two-year-old daughter and attempted to murder her three other children in order to prevent them from suffering the horrors of slavery as she herself had known them.7) In the case of Dabydeen’s poem, however, the immediate source of inspiration is not an ephemeral if compelling piece of abolitionist journalism but the more culturally enduring and elevated painting of Turner’s The Slave Ship, an image that is itself a kind of retelling, too.

In rearticulating the story of the slave-mother and the baby girl she kills (respectively renamed in her novel as Sethe and the eponymous Beloved), Morrison’s overriding concern is to develop a sense of what she elsewhere calls the slave’s “interior life” (“The Site of Memory” 70), something which, she argues, is largely occluded in both the white archive of which Bassett’s article is a part and the tradition of the African American slave narrative on which Beloved also draws. As Steven Weisenburger puts it, “Beloved returns to us a slave mother [→ page 183] who was always not only the subject of others’ obscurely coded stories about her, but far more significantly herself a thinking and feeling subject” (10). A similar point might be made about the project of “Turner,” as Dabydeen in his turn delves into the psychic processes of his own “subject” and plots their rhythms. These are typically recursive, with the poem obsessively looking back to particular events (the child’s fall into the sea and its offensive cry of “‘Nigger’” or the speaker’s plunge into his pond) and underscoring this tendency by means of a widespread pattern of verbal self-echoing. More often than not, this involves the initial lines of individual Cantos: the first line of Canto II (“It plopped into the water and soon swelled”) is repeated almost verbatim in that of Canto IV (“It plopped into the water from a passing ship”), with the time between these two textual moments taken up by an extended digression back into the realms of the speaker’s African past. These aspects of Dabydeen’s poem constitute another of its links to Beloved: Morrison’s text is similarly both fixated on a selection of emotionally charged events and marked by a narrative whose movement is constantly disrupted by the sudden return to (or of) past memories, a formal feature captured in the novel’s insistent “and there it was again” (4).

In both texts, though, such memories tend not to be directly available to consciousness, but are repressed, requiring the intervention of others in order to bring them back to life. In Beloved, this process is primarily undertaken by the ambigraphic figure of Beloved herself, the “fully dressed woman” who mysteriously “walk[s] out of the water” on page 50 of Morrison’s novel and, throughout the text, plays a double part as the reincarnation of Sethe’s dead daughter, on the one hand, and of her African mother, a survivor of the Middle Passage, on the other. In “Turner,” by contrast, it is the “creature that washe[s] towards” (VII.2) the speaker who rekindles memory, “waken[ing]” him to the “years” he had “forgotten” (VII.1) and “burning [his] eyes / Awake” (VII.14-15) with its “salt splash” (VII.14). Such reawakening partly stimulates in him a regressive “lust” (XI.3) for the sensory delights of home, ranging from “the smell / Of earth and root and freshly burst fruit” (XI.3-4) to the “taste of sugared milk” (XI.7),8) [→ page 184] but also occasions recollections that are bound up with the Atlantic crossing and that are hence more typically “obscene” (XI.17). But, however violent the fluctuations of memory’s mood in “Turner,” the moments when its revival is self-consciously announced in the text are, appropriately enough, moments in which the intertextual memory of Beloved is also activated, as in Canto XI. As the speaker indicates at this point, the instant of memory’s return coincides with that in which the child is first jettisoned from the slaver—“It broke the waters,” he states, “and made the years / Stir, not in faint murmurs but a whirlpool / That sucks [him] under” (XI.1-3)—just as Dabydeen’s language is here pregnant with the metaphorical patterns in Beloved, as used, specifically, during the scene in which Sethe first sets eyes on her “girl come home” (201). In this episode, as Sethe gets “close enough to see” Beloved’s “face” and begins to recall the history she has forgotten, she is overwhelmed by the impulse to empty her “bladder,” a process of seemingly “endless” discharge that the novel likens to the unstoppable rush of “water breaking from a breaking womb” (51).

“Turner” and Beloved not only both use birth as a metaphor for the renaissance of the past but also include scenes in which birth is featured as a literal event. These scenes exist in a complex interplay of difference from and similarity to one another. This is a point that can be developed by returning to the in medias res account of blighted labour with which “Turner” begins and comparing it to the equally critical but ultimately triumphant narrative of birth in Beloved. The latter unfolds as the nineteen-year-old Sethe, six months into term with her fourth child and second daughter, attempts to escape from slavery on the Sweet Home plantation by crossing the Ohio River to freedom in Cincinnati, using a stolen boat with “one oar, lots of holes and two bird nests” (83). In “Turner”’s first Canto, it is the mother who is abandoned by her child: she “sobs from the depths of true / Hurt and grief” (I.3-4), sunk beneath her tears in a way which oddly parallels the plight of the stillborn submerged in blood and later water. In the scene in Morrison, conversely, the identity of the bereaved is less fixed and has the potential to be assumed by either [→ page 185] mother or child as their fortunes shift. At one stage, it appears that it will be Sethe’s fate to be the one bereft, as her daughter’s delivery stalls and she seems to be “drowning in [her] mother’s blood” as “river water, seeping through any hole it chose [...] spread[s] over Sethe’s hips” (84), while, at an earlier juncture, it is the daughter herself who is threatened with bereavement. This prospect arises when the exhausted Sethe concludes that she cannot complete the flight from Sweet Home and is condemned “to die in wild onions on the bloody side” (31) of the Ohio, her body little more than a “crawling graveyard for a six-month baby’s last hours” (34). In the event, neither of these scenarios comes to fruition, largely because of Amy Denver, whose last name Sethe transforms into her newborn’s first in recognition of both the selfless ministrations of this impoverished “whitegirl” (76) and, more broadly, the interracial alliance they represent: “‘That’s pretty. Denver. Real pretty’” (85).

In facilitating the “magic” and “miracle” (29) of Denver’s nativity, the dextrous Amy succeeds where Dabydeen’s rough-handed midwives fail, but there are other differences between the two birth-scenes also. When Amy is “walking on a path not ten yards away” and hears Sethe’s “groan” at the thought of “herself stretched out dead while [her] little antelope lived on—an hour? a day? a day and a night?—in her [...] body,” she “stand[s] right still” (31), her sudden stasis not dissimilar to that of Dabydeen’s slaver. Yet, while the slaver’s course is interrupted primarily “for profit’s sake,” Amy halts on compassionate grounds, just as her “dreamwalker’s voice” (79) encourages in the “antelope” a sustaining “quiet” (34) radically at odds with the “stillness” (I.10) befalling its intertextual companion. That said, there is perhaps at least some sense in which Amy too profits from the exemplary kindness of her actions: in rescuing Denver from engulfment and Sethe from death, she at the same time masters two of her own past traumas—the vision of the “drowned” “nigger” who “float[s] right by [her]” when she is “fishing off the Beaver once” (34) and her “mama”’s demise “right after” (33) she is born.

While it would be wrong to overstress this last point, it is an important one even so, not least because it suggests an element of [→ page 186] congruence rather than difference between the scenes in question, since, in “Turner” too, the boundaries between compassion and profit are not always clear or stable. In the captain’s case, the type of profit at issue is economic, but, for the poem’s speaker, profit takes an affective or a psychological form, as the discarded child not only becomes his “bounty” (I.17) and “miracle of fate” (I.19) but also bestows on him the “longed-for gift of motherhood” (I.20): by adopting or appropriating the child, the speaker is able symbolically to reenact the very relationship with his own mother that the slave trade has severed, thus initiating his own version of the quest for a lost maternal love—that “clamor for a kiss” (275)—that so consumes Morrison’s novel. In this respect, the naming of the stillborn as “Turner” is entirely apposite, as it is indeed turned from being “mere food for sharks” (I.21) into the resourceful speaker’s “fable” (I.22), while simultaneously turning him from male to female.

The speaker’s identification with his own mother is partly a matter of timbre and storytelling, as, for instance, in the moments when he considers how best to address “this thing” that is at once “drawn” to him and “yet / Struggling to break free” (XIX.2-3). “Shall I call to it in the forgotten / Voice of my mother” (XIX.1-2) he muses, wondering later if he should also “suckle / It on tales of resurrected folk” (XX.5-6) to satisfy its hunger for the “mirage / Of breast” (XIX.3-4) it is “seeking” (XIX.3). More typically, though, identification is a matter of bodily action and, in particular, the embrace. As “Birds gather from nowhere to greet” (VIII.1) this “morsel of flesh” (VIII.3), “Screaming their glee [and] flapping cruel wings” (VIII.2), the speaker responds to this terrifying congregation with his own counter-movement: while in Canto XXV he might be unable to defend himself from the rapacious Yeatsian “Wings of Turner brooding over [his] body” (XXV.20), “white [and] enfolding” (XXV.19),9) he can guard the child from the “vengeful” (IX.8) creatures that encircle it, not only by softening them with “Gentle names—Flambeau, Sulsi, Aramanda” (IX.9)—but also by “gather[ing] it in with dead arms” (XV.1). Here the ambiguity of this phrase intertangles the two pairs of limbs to which it simultaneously refers (the speaker’s and the child’s) in a way which also [→ page 187] intertangles Dabydeen’s poem with Macbeth once more and its own comparison of battling armies to “two spent swimmers that do cling together / And choke their art” (1.2.8-9). But the loving gesture by which the speaker cradles the stillborn also recollects the salvific maternal embraces that bless his early years, played out in a seemingly prelapsarian Africa prior to Turner’s destructive arrival. On one occasion during this phase of the speaker’s life, his mother “buries [him] in the blackness / Of her flesh” (VIII.12-13) when “fevers starch [his] blood” (VIII.10) and, at another time, she “catch[es]” (XII.54) and “pin[s] [him] tightly, always, / To her bosom” (XII.56-57) when he “crie[s] out in panic / Of falling” (XII.55-56) from her lap while “tugg[ing]” too firmly at her “silver nose-ring” (XII.53). And she is also there in the wake of the diving accident discussed above, “pluck[ing] […] up” her son from the side of the pond where he lies injured and carrying him to safety with “huge hands” (XII.27).

Yet, even as the speaker fondly clasps the child to himself in a way that reenacts how he was once embraced maternally, there are points in the poem in which his relationship to his mother appears to be ominously fractured, even before it is ruptured once and for all by the coming of Turner and the initiation into the Middle Passage which this sets in train. One way in which this is illustrated is in the resurfacing memories of “harvest-time” (XV.I) in Africa:

We trooped into the field at first light,

The lame, the hungry and frail, young men

Snorting like oxen, women trailing stiff

Cold children through mist that seeps from strange

Wounds in the land. We float like ghosts to fields

Of corn. All day I am a small boy

Nibbling at whatever grain falls from

My mother’s breast as she bends and weaves

Before the crop, hugging a huge bundle

Of cobs to her body, which flames

In the sun, which blinds me as I look up

From her skirt, which makes me reach like a drowning

Man gropes at the white crest of waves, thinking it

Rope. I can no longer see her face

In the blackness. The sun has reaped my eyes. (XV.2-16)

[→ page 188] As these lines indicate, the process of gathering the “corn” brings mother and child into comforting proximity, yet, at the same time, is shadowed by a sense of growing distance. No longer a suckling imbibing milk but a “small boy,” the speaker must be content with “Nibbling at whatever grain falls from / [His] mother’s breast,” even finding his place there taken by “a huge bundle / Of cobs,” which themselves quietly oust the “jenti cubs / Clinging to their mother’s teats” (IV.37-38) in Canto IV. Such exile is crucially augmented by the way in which this bundle “flames / In the sun,” its brightness blinding the speaker as he looks “up” to his labouring mother and discovers her faceless. As his “eyes” are thus “reaped,” the speaker suffers a quasi-Oedipal trauma that both parallels the “strange / Wounds” marking the misty “land” and links him to those “lame” figures “trooping into the fields.”

In likening these infirm workers and their companions to floating ghosts and then comparing his own predicament to the floundering delusions of a “drowning / Man” who “gropes at the white crest of waves, thinking it / Rope,” the speaker anticipates the moment when Turner suddenly metamorphoses from good mother to bad and flings his charge into the sea.10) At the same time, however, the speaker’s experience looks back, once again, to Beloved and the title character’s interior monologue towards the end of the novel’s second Part. As befits a revenant compounded out of Sethe’s murdered daughter and the mother whom Sethe recalls as little more than “one among many backs turned away from her [and] stooping in a watery field” (30), Beloved articulates her thoughts at this juncture in a double tongue, in which memories of death and of the Middle Passage flow freely into one another:

Sethe went into the sea. She went there. They did not push her. She went there. She was getting ready to smile at me and when she saw the dead people pushed into the sea she went also and left me there with no face or hers. Sethe is the face I found and lost in the water under the bridge. When I went in, I saw her face coming to me and it was my face too. I wanted to join. I [→ page 189] tried to join, but she went up into the pieces of light at the top of the water. (214)

In some ways, this series of breathless reflections is quite different from the harvest-scene just considered: it dramatizes a drowning that is literal rather than metaphorical and voluntarily sought by a suicidal mother rather than involuntarily suffered by a dependent child. But where Morrison’s text and Dabydeen’s connect (or “join”) is in how they imagine the mother’s absence as primarily that of her “face.”

Alongside the mutual preoccupation with the mother-child bond—how it is severed by the institution of slavery and how it can be restored—there are two further elements of common ground between Dabydeen’s poem and Beloved, the first of which emerges from the parallels between Turner and the figure of Morrison’s schoolteacher. Throughout Beloved, the latter not only manages (and torments) the slaves on the Sweet Home plantation after the death of the relatively humane Mr Garner but also places them under constant surveillance, “Talking soft and watching hard” (197) as he “wrap[s]” his “measuring string” (191) around their heads and bodies and instructs his two “nephews” (36) in the art of correctly tabulating Sethe’s “human” and “animal” “characteristics” (193). While Dabydeen’s Turner does not engage in quite the same coldly pseudoscientific studies, he nonetheless shares the faith in the Western rationalism that underpins them and seeks to inculcate a similar belief in his own slaves: as the speaker puts it in Canto II, “since Turner’s days” (II.18) he has “learnt to count, / Weigh, measure, abstract, rationalise” (II.18-19). But Turner also uses his reasoning powers as an equally chilling means of calculating both the quantity and value of the black bodies that (as in the massacre aboard the Zong) he plans to jettison. In Canto XII, he is to be found “sketch[ing] endless numbers” (XII.32) and “multiplying percentages” (XII.46) in his ledger:

He checks that we are parcelled

In equal lots, men divided from women,

Chained in fours and children subtracted

From mothers. When all things tally

He snaps the book shut. (XII.39-43)

[→ page 190] Although economic rather than anthropometric or anthropological in spirit, this sinister volume consolidates the intertextual link with Beloved by recalling the “notebook” (37) in which Morrison’s sotto voce sadist records his observations of the Sweet Home slaves, even extending these to include the scene in which Sethe is euphemistically “nurse[d]” (6) by his “boys” (36) during her pregnancy, “one sucking on [her] breast” and “the other holding [her] down” (70).

The prospect of having “her daughter’s characteristics” listed “on the animal side of the paper” (294) is one of the main motives precipitating both Sethe’s escape from schoolteacher’s regime and her apotropaic slitting of Beloved’s throat just one month later when he comes to claim her back. But an equally powerful influence upon Sethe’s actions is the thought of the daughter’s inevitable rape under that same dispensation, her “private parts invaded,” as Sethe surmises, by a “gang of whites” (251). This aspect of Beloved—white male sexual violence towards the black subject—constitutes the second of the additional elements in the intertextual dialogue between Morrison’s novel and Dabydeen’s poem and can be brought into initial focus by considering the speaker’s accounts of his two sisters, as they appear in Cantos XXII and XXIII, when the poem draws to a close.

As even the most cursory reading of Beloved suggests, the sexual fate Sethe fears for her “beautiful, magical best thing” (251) is, by contrast, part of the daily round for numerous other black females in the novel, one case in point being Ella, a woman whose “puberty” is “spent in a house where she [is] shared by father and son.” Ella designates the latter with the oddly nondescript soubriquet, “‘the lowest yet’” (256), but it is arguable that Dabydeen’s Turner himself qualifies for such a dubious accolade, particularly with regard to his treatment of the speaker’s younger sister, who, by a curious coincidence, is Ella’s virtual namesake:

Afterwards [Turner] will go to Ellar, the second-born,

Whom he will ravish with whips, stuff rags

In her mouth to stifle the rage, rub salt

Into the stripes of her wounds in slow ecstatic

Ritual trance, each grain caressed and secreted

[→ page 191] Into her ripped skin like a trader placing each

Counted coin back into his purse. Her flesh is open

Like the folds of a purse, she receives

His munificence of salt. By the time he has done

With her he has taken the rage from her mouth.

It opens and closes. No word comes. It opens

And closes. It keeps his treasures.

It will never tell their secret burial places. (XXIII.6-18)

In these graphic (if not pornographic) lines, Ellar is subjected to a form of bodily suffering that is powerfully eroticized and can be read as a figurative rape or even the grotesque preparation of the victim for literal violation. Turner “ravish[es]” her with “whips” and then massages “salt” into her “wounds” in a process that merely produces further pain for her but pleasure for him and whose ritualized and entrancing nature is reciprocated in the rhythms of the text. These are strikingly repetitive, as the reader not only twice suffers receipt of the same harrowing information about Ellar’s abuse but is also mesmerized by the kaleidoscopic recycling and echoing of individual words, images and phrases. As Frantz Fanon comments in Black Skin, White Masks, “We know how much of sexuality there is in all cruelties, tortures, beatings” (159), and this episode fully confirms his view, even exploiting the traditional associations between money and semen stirred up in the image of salt as a “coin” placed inside Ellar’s purse-like “flesh.”

Yet it is not only the traumatized Ellar, but also her elder sister, Rima, who is exposed to the “munificence” of Turner’s sexual cruelty, albeit in a way that is neither at first glance obvious nor indeed to be expected from her story as the speaker tells it. As that story starts, Rima—referred to, in another curious intertextual coincidence, as the speaker’s “beloved” (XXII.28)11)—is an “extravagant” (XXII.1) and “wayward” (XXII.19) figure, with little respect, even “as a child” (XXII.2), for the structures of patriarchy, denying her father’s rule, trampling on her brother’s mock-“battleground” (XXII.13) and “Talk[ing] above the voices of the elders” (XXII.20). As the story ends, however, she seems to have been punished by the patriarchal order [→ page 192] she defies, dying in “childbirth” (XXII.23), with the “village idiot whom she / Married out of jest and spite” (XXII.25-26) looking on. Although respected in death and accordingly “bur[ied] [...] / In a space kept only for those who have / Uttered peculiarly” (XXII.28-30), the possibility remains that Rima’s enemies will pursue her into the afterlife, filling it with terrors that require a collective female prophylaxis to keep them at bay. As the speaker anticipates:

And the women will come

Bearing stones, each one placed on her grave

A wish for her protection against kidnapping,

Rape, pregnancy, beatings, men, all men:

Turner. (XXII.34-38)

While Beloved’s murderous “motherlove” (132) would appear to be an effective means of exempting the black female from the predations of the white man, the strange and disturbing implication of this peculiar utterance is that such drastic steps are not guaranteed to succeed in every case and that death itself may be no refuge.

Together with its emphasis on the sexual violence white males inflict upon black females, Beloved also acknowledges the homosexual violence these “men without skin” (210) visit upon the black male. This is encapsulated most clearly in the account of Paul D’s induction into the oral traditions governing the coffle he is forced to join in Georgia:

Chain-up completed, they knelt down. The dew, more likely than not, was mist by then. Heavy sometimes and if the dogs were quiet and just breathing you could hear doves. Kneeling in the mist they waited for the whim of a guard, or two, or three. Or maybe all of them wanted it. Wanted it from one prisoner in particular or none—or all.

‘Breakfast? Want some breakfast, nigger?’

‘Yes, sir.’

‘Hungry, nigger?’

‘Yes, sir.’

‘Here you go.’

Occasionally a kneeling man chose gunshot in his head as the price, maybe, of taking a bit of foreskin with him to Jesus. Paul D did not know that [→ page 193] then. He was looking at his palsied hands, smelling the guard, listening to his soft grunts so like the doves’, as he stood before the man kneeling in mist on his right. Convinced he was next, Paul D retched—vomiting up nothing at all. (107-08)

In this snapshot of “breakfast” in America, the slaves’ chained and “Kneeling” posture ironically recalls the image created by Josiah Wedgwood in 1787 that became one of the most familiar components of abolitionist iconography in both Britain and America. At the same time, the posture links them to a rather more obscure black figure, in the form of the statuette Denver encounters as she leaves the residence of the novel’s own erstwhile abolitionists, the Bodwins, the “white brother and sister who […] hated slavery worse than they hated slaves” (137). Though not an image of a slave at least, this figurine is nonetheless strongly expressive of ongoing racial inferiority amid the Reconstruction era of the early 1870s in which the novel’s present action takes place. The artefact represents a black subject posed “on his knees” atop a “pedestal” bearing the legend “‘At Yo Service’” and moulded in caricature: he has “eyes” “Bulging like moons [...] above [a] gaping red mouth” filled with “coins,” with these features set within a “head thrown back farther than a head could go” (255). Equally, though, as much as it links them to this florid sign of a racism still unchallenged even among progressive whites, the slaves’ position on the chain-gang quietly looks beyond the sublunary horizons of the white world that oppresses them. As they kneel, the slaves suggest a prayerfulness which in turn suggests “obedience” neither to the “hammer at dawn” (107) nor the grunting guards but to a higher master, in the shape of “Jesus,” whose redemptive presence is registered, albeit faintly, by the cooing of the distant “doves.”

Such homosexual abuse as is dramatized in Beloved’s coffle-scene is an important feature of “Turner” also. For much of the poem, it is something only hinted at, as, for example, in those “fat hands” (XVI.20) of Canto XVI, “Feeling” the speaker’s “weight” and “prying in [his] mouth” (XVI.21); the double entendre with which the physical [→ page 194] spaces of Turner’s slaver become fused with the more intimate recesses of his boys’ anatomy as he kisses them in “quiet corners” (VIII.7) and “Unseen passages” (VIII.8); or, again, in the image of Turner’s “creased mouth / Unfolding in a smile” (VII.43-44) as he “enter[s] / His cabin, mind heavy with care” (XII.44-45) and “beholds / A boy dishevelled on his bed” (XII.46-47). In the course of the poem’s penultimate Canto, however, Turner’s violations of his boys become more overt, even as at this point they are metaphorical in nature rather than literal and carried out in the name of other impositions:

Turner crammed our boys’ mouths too with riches,

His tongue spurting strange potions upon ours

Which left us dazed, which made us forget

The very sound of our speech. Each night

Aboard ship he gave selflessly the nipple

Of his tongue until we learnt to say profitably

In his own language, we desire you, we love

You, we forgive you. He whispered eloquently

Into our ears even as we wriggled beneath him,

Breathless with pain, wanting to remove his hook

Implanted in our flesh. The more we struggled

Ungratefully, the more steadfast his resolve

To teach us words. He fished us patiently,

Obsessively, until our stubbornness gave way

To an exhaustion more complete than Manu’s

Sleep after the sword bore into him

And we repeated in a trance the words

That shuddered from him: blessed, angelic,

Sublime; words that seemed to flow endlessly

From him, filling our mouths and bellies

Endlessly. (XXIV.1-21; italics in original)

As so often in the text, Turner is Protean here, his identity shifting dramatically from one guise to the next. Throughout the Canto, he is most obviously aligned, once again, with Morrison’s schoolteacher, giving his reluctant pupils lessons in English that leave them “dazed” and forgetful of their own “speech.” Yet, the master who conducts his charges across the Lethe that leads from their language to his is also an overbearing mother-figure, his “tongue” a “nipple” “spurting [→ page 195] strange potions” in a way that extends the repertoire of mammary images both in Dabydeen’s poem itself and Macbeth and Beloved. This role is no sooner assumed, however, than it is usurped by Turner the paedophile, implanting his “hook” in the “flesh” that “wriggle[s]” beneath him and is “Breathless with pain.” These two identities—of Turner as tyrannical mother and as suffocating abuser—coalesce in the ironically terminal description of Turner’s “shudder[ing] […] words […] flow[ing] endlessly” into his young slaves’ defenceless “mouths and bellies”—like breastmilk or semen or a mix of both.12)

As noted earlier, the speaker behaves towards the stillborn child who navigates the fluctuating course of his 783-line monologue as his mother formerly behaved towards him: the care he gives it recapitulates the care he once received, thus allowing him to restore his past and vicariously reclaim a love otherwise lost. Equally and more troublingly, however, the speaker’s treatment of the child also possesses a family resemblance to that which he experiences from Turner, as becomes clear at the start of the poem’s final Canto:

‘Nigger,’ [the child] cries, loosening from the hook

Of my desire, drifting away from

My body of lies. I wanted to teach it

A redemptive song, fashion new descriptions

Of things, new colours fountaining out of form.

I wanted to begin anew in the sea

But the child would not bear the future

Nor its inventions, and my face was rooted

In the ground of memory. (XXV.1-9)

Like Turner’s, the speaker’s “desire” (significantly figured here as a “hook”) is to “teach” the child, though he is evidently not as adept in this enterprise as his model. In the one case, the pupils capitulate to their instructor in a state of “exhaustion” so “complete” (XXIV.15) that all they can do is chant back the hypnotic “words” (XXIV.17) they hear—“blessed, angelic, / Sublime” (XXIV.18-19)—but, in the other, the student will not be brainwashed, rejecting what he is taught as a “body of lies” and ultimately emerging, indeed, as the true pedagogue. In that bleakly authoritative “‘Nigger,’” what the child [→ page 196] demonstrates to the speaker is that the wish “to begin anew in the sea”—breaking away from their common history—is impossible. This is a point Dabydeen underlines by once more resorting to the device of internal echo and recycling here the selfsame phrase as first appears in the “Preface,” as if the poem is unable to break free from its own origin.

It is the realization of history’s inescapability that prompts the speaker himself to follow the child’s scornful lead and turn against the authority of his own narrative, rejecting his autobiography as no more reliable or authentic than the hope for a future sealed off from the “Preface”’s “memory of ancient cruelty” (x). His final utterance is, accordingly, a resounding palinode:

No savannah, moon, gods, magicians

To heal or curse, harvests, ceremonies,

No men to plough, corn to fatten their herds,

No stars, no land, no words, no community,

No mother. (XXV.38-42)

Among this catalogue of negations, the most significant for this essay is the speaker’s claim that he has “no community.” In one respect, this is all too poignantly true, especially given the fact that he has just been abandoned by his unwilling confidant, who “dips / Below the surface” (XXV.16-17) of the sea they share and “frantically […] tries to die” (XXV.17). From an intertextual perspective, however, the claim is anything but persuasive, since “Turner” is rich with community, engaging in a play of call and response with a wide array of other voices.

Conclusion: Beginning Anew

To recall “Turner”’s “Preface” one last time, this essay enables work on Dabydeen’s poem to “begin anew,” taking the critical debate beyond the frame of reference that the “Preface” sets up (and that “Turner”’s critics have largely replicated), raising questions about the [→ page 197] interpretative authority writers can (or cannot) exert over their own creations: it directs attention to parts of Ruskin’s “Of Water, as Painted by Turner” that are rarely if ever considered in readings of Dabydeen’s poem and, more significantly, to Macbeth and Beloved, texts whose importance to an understanding of “Turner” has been similarly “submerged” in the critical seas that have washed over the text in the years since its publication.

As it conducts that latter double exchange, “Turner” further encourages us to ponder the intertextual links between Shakespeare’s Renaissance tragedy and Morrison’s late twentieth-century novel, both of which pivot, after all, around different types of murder and the guilt that springs from them and feature supernatural agencies (to suggest only two of the most obvious commonalities). The conversation that might be going on between those two ostensibly disparate texts is a topic for another occasion, but its existence perhaps accounts for the texts’ copresence as central elements in Dabydeen’s remarkable poetic project.

Cardiff University

Works Cited

Armstrong, Tim. “Catastrophe and Trauma: A Response to Anita Rupprecht.” Journal of Legal History 28.3 (2007): 347-56. DOI: 10.1080/01440360701698510.

Baucom, Ian. Specters of the Atlantic: Finance Capital, Slavery, and the Philosophy of History. Durham, NC: Duke UP, 2005.

Boeninger, Stephanie Pocock. “‘I Have Become the Sea’s Craft’: Authorial Subjectivity in Derek Walcott’s Omeros and David Dabydeen’s ‘Turner.’” Contemporary Literature 52 (2011): 462-92. <http://www.jstor.org/stable/41472504> (available after free registration at JSTOR).

Costello, Leo. J. M. W. Turner and the Subject of History. Farnham: Ashgate, 2012.

Craps, Stef. Postcolonial Witnessing: Trauma out of Bounds. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013.

Dabydeen, David. Pak’s Britannica: Articles by and Interviews with David Dabydeen. Ed. Lynne Macedo. Kingston, Jamaica: U of the West Indies P, 2011.

Dabydeen, David. “Turner.” Turner: New & Selected Poems. London: Cape, 1994. 1-40.

Döring, Tobias. Caribbean-English Passages: Intertextuality in a Postcolonial Tradition. London: Routledge, 2002.

Eliot, T. S. “The Dry Salvages.” The Complete Poems and Plays of T. S. Eliot. London: Faber, 1969. 184-90.

Falk, Erik. “How to Really Forget: David Dabydeen’s ‘Creative Amnesia.’” Readings of the Particular: The Postcolonial in the Postnational. Ed. Anne Holden Rønning and Lene Johannessen. Amsterdam: Rodopi, 2007. 187-204.

Fanon, Frantz. Black Skin, White Masks. Trans. Charles Lam Markmann. London: Pluto P, 1986.

Frost, Mark. “‘The Guilty Ship’: Ruskin, Turner and Dabydeen.” Journal of Commonwealth Literature 45.3 (2010): 371-88. DOI: 10.1177/0021989410377270.

Grant, Kevin, ed. The Art of David Dabydeen. Leeds: Peepal Tree, 1997.

Gravendyk, Hillary. “Intertextual Absences: ‘Turner’ and Turner.” Comparatist 35 (2011): 161-69. <http://www.jstor.org/stable/26237268> (available after free registration at JSTOR).

Härting, Heike H. “Painting, Perversion, and the Politics of Cultural Transfiguration in David Dabydeen’s Turner.” No Land, No Mother: Essays on the Work of David Dabydeen. Ed. Kampta Karran and Lynne Macedo. Leeds: Peepal Tree, 2007. 48-85.

Harris, Middleton A., Morris Levitt, Roger Furman, and Ernest Smith, eds. The Black Book: 35th Anniversary Edition. New York: Random House, 2009.

Jenkins, Lee M. “On Not Being Tony Harrison: Tradition and the Individual Talent of David Dabydeen.” ARIEL 32 (2001): 69-88. <http://journalhosting.ucalgary.ca/index.php/ariel/article/view/34460/28496>.

Jones, Neil. “The Zong: Legal, Social and Historical Dimensions. “ Journal of Legal History 28.3 (2007): 283. DOI: 10.1080/01440360701698395.

Lewis, Andrew. “Martin Dockray and the Zong: A Tribute in the Form of a Chronology.” Journal of Legal History 28.3 (2007): 357-70. DOI: 10.1080/01440360701698551.

Lobban, Michael. “Slavery, Insurance and the Law.” Journal of Legal History 28.3 (2007): 319-28. DOI: 10.1080/01440360701698452.

Lyall, Andrew. Granville Sharp’s Cases on Slavery. Oxford: Hart, 2017.

Mackenthun, Gesa. Fictions of the Black Atlantic in American Foundational Literature. London: Routledge, 2004.

McCoubrey, John. “Turner’s Slave Ship: Abolition, Ruskin, and Reception.” Word & Image: A Journal of Verbal / Visual Inquiry 14 (1998): 319-53. DOI: 10.1080/02666286.1998.10443961.

May, Stephen J. Voyage of The Slave Ship: J. M. W. Turner’s Masterpiece in Historical Context. Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2014.

Morrison, Toni. Beloved. London: Vintage, 1997.