Agency in Vaughan's Sacred Poetry: Creative Acts or Divine Gifts?

Donald Dickson

Published in Connotations Vol. 9.2 (1999/2000)

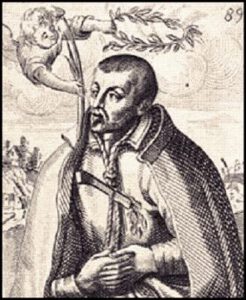

Henry Vaughan was certainly familiar with the classical trope of the poem as child "fathered" by its creator. Like many poets of the Renaissance, he made witty use of it in both his early volumes of secular verse to emphasize his role as procreator. Yet in the volume of religious poems for which he is justly celebrated, Silex Scintillans (1650, 1655), he maintained that God was the "author" of his poems. In this essay I want to explore what the absence of the poet−as−father metaphor implies about the source of the inspiration for Vaughan's religious poems.

As Ernst Curtius reminds us, the notion that poets leave behind immortal children in their works goes back to Plato's Symposium (208d−209e), where Diotima explained that some seek immortality of the body by begetting children while others seek immortality of the soul through literary "offspring."1) The Greeks, of course, called the poet a "maker" (πoιητής). Similarly, Ovid in his Tristia (III, 14) identified his carmina, which were created sine matre, as stirps haec progeniesque; thereafter, according to Curtius, partus came to be a synonym for a literary work.

During the Renaissance the classical metaphor was most popular with the poet sometimes figured as "mother" though more usually as "father" of a literary corpus. For example, in the well−known first sonnet of Astrophel and Stella, Sidney compared the making of a poem the labors of childbirth.

Thus great with child to speak, and helpless in my throes,

Biting my trewand pen, beating myself for spite,

Fool, said my Muse to me, look in thy heart and write.2)

[→page 175] Shakespeare's sonnets were dedicated to Mr. W. H., or Mr. W[illiam] S[hakespeare], in either case, to "the onlie begetter of these insuing sonnets." And Jonson memorialized the death of his seven year−old son, "thou child of my right hand, and joy," in a deeply personal epigram that Vaughan would have certainly known. Jonson, whose father died before he himself was born, shared his own name—"dexterous" or "fortunate" in Hebrew—with a son for whom he had entertained high hopes. A son who was as much a part of himself as his right hand, the hand that produced his art, giving rise to his immortal couplet:

Rest in soft peace, and, asked, say, here doth lie

Ben Jonson his best piece of poetry.3)

For Jonson, this trope was central to his humanist belief in the power of poetry to shape or fashion the self, as he explained more fully in his tribute to Shakespeare:

… And that he

Who casts to write a living line must sweat,

(Such as thine are) and strike the second heat

Upon the muses' anvil: turn the same

(And himself with it) that he thinks to frame;

Or for the laurel he may gain a scorn:

For a good poet's made, as well as born.4)

This metaphor captures the essence of Jonson's humanism, which was derived in part from Horace, Seneca's moral epistles, and ultimately Aristotle: by forging verse as well as his own character upon the anvil, the poet helped to create the morally superior people required to govern society. Good poets and good poems were made as well as born. Thus the possibility of human agency—of making—was strongly endorsed.

Since the young Henry Vaughan attached himself to the remaining Sons of Ben while in London in the early 1640s and imitated the work of Jonson (and certainly knew the antique poets who began this tradition), it is not surprising that he employed this trope himself. In both his early volumes of secular verse, he used it to accentuate the poet as maker or self−sufficient creator of poetic worlds. For instance, in "A Rhapsody: Occasionally written upon a meeting with some of his friends at the Globe Tavern, in a Chamber [→page 176] painted over head with a Cloudy Sky, and some few dispersed Stars, and on the sides with Land−scapes, Hills, Shepherds, and Sheep," that was published in his Poems of 1646 and that pays obvious homage to the literary gathering favored by Jonson, he wrote:

Drink deep; this cup be pregnant; & the wine

Spirit of wit, to make us all divine,

That big with sack, and mirth we may retire

Possessors of more souls, and nobler fire;

And by the influx of this painted sky,

And laboured forms, to higher matters fly;

So, if a nap shall take us, we shall all,

After full cups have dreams poetical.

Let's laugh now, and the pressed grape drink,

Till the drowsy Day−Star wink;

And in our merry, mad mirth run

Faster, and further than the Sun;

And let none his cup forsake,

Till that Star again doth wake;

So we men below shall move

Equally with the gods above.5)

As in Milton's Elegia sexta where the virtues of wine as an aid to the muses are extolled, the wine goblet is said to be pregnant with the spirit of wit: the pun here is on spiritus vini and the "spirit generative," to which Shakespeare alluded in Sonnet 129. Made big with sack, the poets at the Globe Tavern will then labour to produce forms of higher matters under the astrological influences or influx of the stars painted on the ceiling. And if the pregnant cup fail to produce poetic forms, it will at least lead to poetic reveries in the form of dreams in their post−prandial napping. Thus intoxicated with this creative force, the poets will move equally with the gods above.

Similarly, in his second volume, Olor Iscanus (1647), Vaughan played with the trope of the creative act in a Latin poem to his former tutor, which may also owe something to Jonson's tribute to his own schoolmaster, William Camden, as well as to the epigram to Jonson's son. It is titled "Venerabili Viro, PrÆceptori suo olim & semper Colendissimo Magistro. Mathaeo [→page 177] Herbert" ["To the Venerable Mr. Matthew Herbert, Formerly His Tutor and Always His Most Cherished Friend"]. Rector of nearby Llangattock, Matthew Herbert had tutored both the Vaughan twins (and Thomas also offered several poems in his praise).

Quod vixi, Mathaee, dedit pater, haec tamen olim

Vita fluet, nec erit fas meminisse datam.

Ultra curasti solers, perituraque mecum

Nomina post cineres das resonare meos.

Divide discipulum: brevis haec & lubrica nostri

Pars vertat patri, posthuma vita tibi.

* * *

My father gave me life, Matthew, but this life will one day slip away, and the gift will not even be remembered. Skilfully you have made provision for me beyond this, and you enable that name, which would have perished with me, to re−echo after my death. Divide the life of your pupil in two: let this brief and fleeting part redound to my father's credit; to yours, my existence beyond the grave.6)

Here, in what might be termed a paean to the poet's two bodies, Vaughan acknowledged that his father gave life to the mortal body, while his tutor gave him an immortal one. By nurturing his poetic gifts, the tutor has helped create a name that will re−echo after his death through the imperishable bodies of his poems.

Shortly after finishing Olor Iscanus (whose preface is dated 17 December 1647), Vaughan, as is well known, went through a spiritual crisis, either as a result of the death of his brother William, some illness of his own, or the general disruptions caused by the Civil War—when, for example, both his brother and his tutor were dispossessed of their livings by the Parliamentarian authorities. Whatever the cause, the result was Vaughan's conversion to the religious verse of George Herbert and all that this entailed. The emblematic title−page to Silex Scintillans 1650 shows the thunderbolt of Jupiter tonans, i.e., the hand of God, reaching out from the clouds to strike sparks and produce tears from the flinty heart of the poet. In the one−stanza dedicatory poem used in the first edition of Silex, "To My Most Merciful, [→page 178] My Most Loving, and Dearly Loved Redeemer," he explained that the blood of Christ has re−vivified both his heart and his poetry:

My God! thou that didst die for me,

These thy death's fruits I offer thee;

Death that to me was life and light,

But dark and deep pangs to thy sight.

Some drops of thy all−quickening blood

Fell on my heart; those made it bud

And put forth thus, though Lord, before

The ground was cursed, and void of store.

Indeed I had some here to hire

Which long resisted thy desire,

That stoned thy servants, and did move

To have thee murdered for thy love;

But Lord, I have expelled them, and so bent,

Beg, thou would'st take thy tenant's rent. (ll. 1−14)

Before his conversion, his heart was as stony as the wicked tenants', who had killed the rightful heir to the vineyard in the parable from Matthew (21:33−41) to which he alludes. As a result of these transformations wrought by Christ's all−quickening blood, the poet can offer the fruit of this new life back to its rightful owner. For this spiritual growth to continue, as we learn from the final poem of Silex I, someone else's hand must first wipe out or blot the sinful book of his heart.

King of Mercy, King of Love,

In whom I live, in whom I move,

Perfect what thou hast begun,

Let no night put out this Sun;

Grant I may, my chief desire!

Long for thee, to thee aspire,

Let my youth, my bloom of days,

Be my comfort, and thy praise,

That hereafter, when I look

O'er the sullyed, sinful book,

I may find thy hand therein

Wiping out my shame, and sin.

O it is thy only Art

To reduce a stubborn heart,

… .7)

[→page 179] Vaughan's metaphor links the flinty heart, portrayed so memorably on the emblematic title page to Silex, with St. Paul's understanding of the new covenant, "written … not in tables of stone, but in fleshy tables of the heart" (2 Cor. 3:3 AV, discussed below). It affirms that God is the true author of this book.

When Vaughan published the second edition of Silex Scintillans in 1655, he added two more stanzas to this dedicatory poem, in which he made even clearer the fact that this new vein of poetry was a gift from God.

Dear Lord, 'tis finished! and now he

That copied it, presents it thee.

'Twas thine first, and to thee returns,

From thee it shined, though here it burns;

If the Sun rise on rocks, is't right,

To call it their inherent light?

No, nor can I say, this is mine,

For, dearest Jesus, 'tis all thine.

…

I nothing have to give to thee,

But this thy own gift, given to me;

Refuse it not! for now thy token

Can tell thee where a heart is broken.8)

These flashes of light, these moments of spiritual illumination and poetic inspiration, belong properly to God. He had merely copied out the lines. And in a final coda to Silex II, he implores Christ to inscribe his law in mankind's hearts ("L'Envoy" ll. 50−58).

In Vaughan's devotional poetry, the metaphor of the poem as offspring or creation of the poet, which he had used to such effect in his secular poems, is conspicuous by its absence. It would be an over−simplification to contend that, following his religious conversion, he came to recognize that his own efforts were insufficient theologically and that God was the only sufficient author of all things. To strike nearer the mark we should examine how Vaughan's poetic master, Herbert, anguished over this same dilemma. The opening poem in the central section of The Temple, "The Altar," connects writing poetry with the transformation of the heart of stone into a fleshy heart as the foundation for the new temple. As I have argued [→page 180] elsewhere, "The Altar" features the poet's desire to offer the broken pieces of his heart, framed ingeniously into the hieroglyphic altar, as a claim to merit.9) The poet's desire to write—to create a personal account of the self—is an expression of his desire to offer something back to God as recompense, especially in the early sequence of poems introduced by "The Altar." These, I believe, are the "many spiritual Conflicts" Herbert on his deathbed described to Nicholas Ferrar. If I am correct in my reading of the last poem in The Temple, "Love (III)," even at the end of his journey, when in God's presence, he cannot let go of his desire to "serve," i.e., to justify himself through works. Herbert struggled to reconcile himself to the fact that true representation was possible only when he surrendered his personal story for the typological one that represented his true life's story. What he struggled to understand was that his own story had already been laid out for him in God's writing. As Åke Bergvall reminds us, Augustine held that the opening verse of the Gospel according to John ("In the beginning was the Word") also meant that the creation of the universe in Genesis was accomplished by the efficacious operative power of the logos and that this word was then made flesh. Consequently, the Scripture is more than just the record of God's chosen people and of the ministry of Jesus Christ; the efficacious power of the divine logos is still contained within.10)

Nowhere, in my estimation, is Vaughan's indebtedness to Herbert more clear than in his respect for the power of the "word made flesh" (John 1:14) and his use of the master narratives of the Bible. Or, as he put it so succinctly, "Thy own dear people pens our times, ⁄ Our stories are in theirs set down."11) These lines echoed Herbert's explicitly typological poem "The Bunch of Grapes" (l. 11) and made evident Vaughan's own understanding that Scripture tells the story of the Christian Everyman. In a sonnet praising the Bible as the "key that opens to all mysteries," he expressed the hope that Christ would write upon his stony heart so that its mysteries could be meetly expressed.

Welcome dear book, soul's joy, and food! The feast

Of spirits, heaven extracted lies in thee;

Thou art life's charter, the Dove's spotless nest

Where souls are hatched unto Eternity.

[→page 181] In thee the hidden stone, the manna lies,

Thou art the great elixir, rare, and choice;

The key that opens to all mysteries,

The Word in characters, God in the voice.

O that I had deep cut in my hard heart

Each line in thee! Then would I plead in groans

Of my Lord's penning, and by sweetest art

Return upon himself the Law, and Stones.

Read here, my faults are thine. This Book, and I

Will tell thee so; Sweet Saviour thou didst die!12)

While this trope comes from Ezekiel and was a crucial text for St. Paul, Vaughan would have found it everywhere in the opening sequence to The Temple, especially "The Sinner":

Yet Lord restore thine image, heare my call:

And though my hard heart scarce to thee can grone,

Remember that thou once didst write in stone.13)

In "Holy Scriptures," thus, Vaughan candidly acknowledges that the divine author of Scripture must also inscribe his heart in order for him to be able to offer something back to God—even his groans were "Of my Lord's penning."

For this reason, I believe, Vaughan began his 1655 Preface with an attack on those wits who produce vain trifles of the sort he had himself produced earlier:

That this kingdom hath abounded with those ingenious persons, which in the late notion are termed wits, is too well known. Many of them having cast away all their fair portion of time, in no better employments, than a deliberate search, or excogitation of idle words, and a most vain, insatiable desire to be reputed poets; leaving behind them no other monuments of those excellent abilities conferred upon them, but such as they may (with a predecessor of theirs) term parricides, and a soul killing issue; for that is the Βραβείov, and laureate crown, which idle poems will certainly bring to their unrelenting authors.14)

In these lines, as Alexander Grosart pointed out long ago, Vaughan echoed the sentiments of Robert Greene's Groats−worth of Wit (1596), who wished [→page 182] to consign his "vain fantasies" and "lewd lines" to the fire lest they prove parricides by killing their father's soul.15) Here we have an unmistakably negative use of the metaphor that helps clarify the fine line Vaughan hopes to tread. In his new mode of poetry, following the example of "the blessed man, Mr. George Herbert, whose holy life and verse gained many pious converts," he will make "a wise exchange of vain and vicious subjects, for divine themes and celestial praise."16) Like Herbert, however, he knows that writing idle poems can undermine his efforts to submit to God's "writing."

O! 'tis an easy thing

To write and sing;

But to write true, unfeigned verse

Is very hard! O God, disperse

These weights, and give my spirit leave

To act as well as to conceive!17)

To write the true hymns to which he aspired meant that his own part in their creation was secondary to God's: so he asked God to make him sufficient for this task: to give my spirit leave to act as well as to conceive. While the verb conceive was usually associated with the feminine aspects of procreation in the sense of to receive seed in the womb, it could also mean to beget, "especially in expressions originating in the English version of the Creed" (OED I.1.b). This secondary usage accords well with the dominant role ascribed to the male in Aristotelian reproductive physiology (females were believed to be mere repositories and incubators for the largely male creative force). Just as Christ, in the formulation of the Apostles' Creed, "was conceived by the Holy Ghost," this same indwelling presence will make it possible for the Christian poet to act and to create.

The difficulties as well as the rewards of submitting to God's discipline were also made clear in "Disorder and Frailty," where he

pleaded:

Let not perverse,

And foolish thoughts add to my bill

Of forward sins, and kill

That seed, which thou

In me didst sow,

[→page 183] But dress, and water with thy grace

Together with the seed, the place;And for his sake

Who died to stake

His life for mine, tune to thy will

My heart, my verse.18)

Here, he entreated God to tune his heart so that his verse would be likewise tuned, echoing the sentiments of Herbert's "The Temper (I)": "This is but tuning of my breast, ⁄ To make the musick better." The poem following "Disorder and Frailty" in Silex, called "Idle Verse," appropriately took up the theme treated in the Preface, i.e., that secular verse was unfit employment for gifted poets.

Given the evidence already cited, it might seem plausible that, in regard to poetic creation, Vaughan believed that human agency was illusory, that God elects to use some as passive conduits, or mere amanuenses, for His own sacred verse. Jonathan Goldberg, in fact, believes Herbert to be a poet without a voice of his own and argues that The Temple is really a "representation of God writing, a (dis)owning which locates both God and the subject in a text that is always in quotation marks."19) I cannot agree with his reading of Herbert, nor would I place Vaughan with the Puritans or Calvinists on the issue of free will. His scorn for those who pretended to an "inner light" that justified their overturning the traditional forms of worship, such as the Prayer Book he held so dear, is well documented.20)

Nonetheless, as we have seen, Vaughan affirmed throughout Silex Scintillans that God was the author and he, merely the copyist. To understand what poets such as Herbert and Vaughan mean when they made such statements, we need to examine more closely the Pauline notion of the indwelling of Christ and the context of the lines from Corinthians quoted above, in which the nature of the new covenant is expressed by dramatic contrast with its biblical type, the tables of the Mosaic law written in stone. St. Paul's explanation here provided a cornerstone for his concept of the radical inwardness of Christianity itself by explaining the relationship of the Hebrew Bible to the New Testament.21) In his letter Paul told the Corinthians that Christ had written this new covenant on their hearts, thereby transforming them into sufficient ministers of this new testament. [→page 184] Through grace and the Holy Spirit, their stony hearts would be given new life. As he explained, "Not that we are sufficient of ourselves to think any thing as of ourselves; but our sufficiency is of God; Who also hath made us able ministers of the new testament; not of the letter, but of the spirit: for the letter killeth, but the Spirit giveth life" (2 Cor. 3:5−6). The dilemma over the "authorship" of Vaughan's sacred poems, I think, can be resolved by the notion of sufficiency from Corinthians: God empowers the poet to write by giving his "spirit leave to act as well as to conceive," as he had hinted mysteriously in "Anguish" (ll. 13−18). Inspired and made sufficient by the Holy Spirit, Vaughan, through a cooperative process of authorship, can in turn beget the "true, unfeigned verse" he had hoped for in his Preface. In this way the poet can be said both to conceive and create because of the indwelling spirit. In the final analysis, then, Vaughan can describe the poet inspired by God as both copyist and as author.

Late in his life Vaughan offered a similar view of the source of the poet's inspiration in an anecdote about Welsh bards recounted for his kinsman John Aubrey, with whom he had begun to correspond when Aubrey was collecting biographical data for Anthony Wood's Athenæ Oxonienses. Ever pursuing antiquarian lore, Aubrey had apparently asked Vaughan to make inquiries about Welsh poets, both ancient and modern. In reply Vaughan offered a marvelous tale about the origins of Welsh furor poeticus, taken from John David Rhys's Cambrobrytannicæ Cymbraecæue linguæ institutiones (London, 1592):

I received yours & should gladly have served you, had it bine in my power. Butt all my search & consultations with those few that I could suspect to have any knowledge of Antiquitie, came to nothing; for the ancient Bards (though by the testimonie of their Enemies, the Romans;) a very learned societie: yet (like the Druids) they communicated nothing of their knowledge, butt by way of tradition: wch I suppose to be the reason that we have no account left vs: nor any sort of remains, or other monuments of their learning, or way of living.

As to the later Bards, who were no such men, but had a societie & some rules & orders among themselves: & severall sorts of measures & a kind of lyric poetrie: wch are all sett down exactly In the learned John David Rhees, or Rhesus his welch, or British grammar: you shall have there (in the later end of his book) a most curious account of them. This vein of poetrie they call Awen, which in their language signifies as much as Raptus, or a poetic furor; & (in truth) as many of [→page 185] them as I have conversed with are (as I may say) gifted or inspired with it. I was told by a very sober & knowing person (now dead) that in his time, there was a young lad[,] father & motherless, & soe very poor that he was forced to beg; butt att last was taken vp by a rich man, that kept a great stock of sheep vpon the mountains not far from the place where I now dwell. who cloathed him & sent him into the mountains to keep his sheep. There in Summer time following the sheep & looking to their lambs, he fell into a deep sleep; In wch he dreamt, that he saw a beautifull young man with a garland of green leafs vpon his head, & an hawk vpon his fist: with a quiver full of Arrows att his back, coming towards him (whistling several measures or tunes all the way) & att last lett the hawk fly att him, wch (he dreamt) gott into his mouth & inward parts, & suddenly awaked in a great fear & consternation: butt possessed with such a vein, or gift of poetrie, that he left the sheep & went about the Country, making songs vpon all occasions, and came to be the most famous Bard in all the Countrey in his time.22)

It is tempting to read this anecdote as a not−so−veiled story about his own conversion: the young spiritual orphan who was adopted by a rich man and entrusted with his flocks; when the shepherd proved faithful, he was rewarded with a dream vision and then violently given the gift of poetry, thereafter becoming the most famous Bard in all the Countrey in his time. This story seems to be an original one: Stith Thompson's Motif−Index of Folk Literature does not list any analogue, though birds have long been used as symbols for the soul in the earliest Christian art, either with the Christ child holding a bird in his hands or holding one tied with a string.23) In secular literature, such as the Volsunga Saga or Chaucer's Troilus and Criseyde, the hawk was associated with the nobility or symbolized the pleasures of the chase and temporal life as opposed to the cloister.24) From his readings in hermetic literature, Vaughan may have encountered the hawk as a symbol for the Egyptian god Horus, used because of its fecundity and sharp sight.25) One idea for which many parallels in folk−literature exist, ingesting a magical substance, may also owe something to the burning coal brought by a winged seraph to purify Isaiah's unclean lips (6:6).32) The hawk may even represent the Holy Spirit, whose possession of the poet is reminiscent of the arm of God violently striking the flint to produce tears and poetry in Silex Scintillans. For a poet like Vaughan who was largely uninterested in the glories of his native Welsh countryside, it is more than curious that the dream messenger was a "green man," some tutelary spirit [→page 186] of Nature, armed with arrows and crowned with greens. This anecdote, in any case, reinforces the scattered references in Silex Scintillans attributing "true, unfeigned verse" to some divine source.

Similarly, his twin brother Thomas—in both his published writings and his manuscript notebook (British Library MS. Sloane 1741)—attributed his greatest successes to someone or something beyond the veil. Like many alchemists, Thomas Vaughan believed success in the great work was always a donum dei. Success came, he confessed, "not by my owne witt, or labour, but by gods blessing." For example, on the very day his wife and research partner, Rebecca, was taken from him in death, he recounted how he was compensated with the memory of a formula long since forgotten:

Memoriæ Sacrum.

On the same Day my deare wife sickened, being a Friday, and at the same time of the Day, namely in the Evening: my gracious god did put into my heart the Secret of extracting the oyle of Halcali, which I had once accidentally found att the Pinner of Wakefield, in the Dayes of my most deare Wife. But it was againe taken from mee by a wonderfull Judgement of god, for I could never remember how I did it, but made a hundred Attempts in vaine. And now my glorious god (whose name bee praysed for ever) hath brought it againe into my mind, and on the same Day my deare wife sickened; and on the Saturday following, which was the day shee dyed on, I extracted it by the former practice: Soe that on the same dayes, which proved the most sorowfull to me, that ever can bee: god was pleased to conferre upon mee ye greatest Joy I can ever have in this world, after her Death.

The Lord giveth, and the Lord

taketh away: Blessed bee the Name

of the Lord. Amen! T. R. V.26)

Vaughan plainly regarded God's gift of the formula as recompense for losing his young wife.

Similarly he regarded two dreams that occurred on successive nights near the first anniversary of her death as gifts from beyond. On the evening of 8 April 1659, suffering from a "suddaine Heavines of spirit, but without any manifest Cause whatsoever," he related that before laying down to sleep he prayed contritely for pardon from his sins and to be reunited with [→page 187] his wife. During the night he discovered that God had fore−ordained their marriage. In the dream he declared to his friends that his father had chosen a beautiful mate for him, with whom he immediately fell in love. In a marginal note Thomas clarified that "This was not true of our temporall mariage, nor of our natural parents, and therefore it signifies som greater mercie," which can only mean he believed that God had designated Rebecca for his eternal companion.27) On the following night, "after prayers, and hearty teares," his wife again appeared in an enigmatic dream that hinted at the length of time before their reunion. She was arrayed "in greene silks downe to the ground, and much taller, and slenderer then shee was in her life time, but in her face there was so much glorie, and beautie, that noe Angell in Heaven can have more."28) She appeared to him, that is, as the divine Thalia from his Lumen de Lumine (1651), who was attired "in thin loose silks, but so green, that I never saw the like, for the Colour was not Earthly."29) Thalia, the attendant spirit at the Temple of Nature, guides Eugenius Philalethes (Vaughan's pseudonym and alter ego) in his search for the prima materia for the magnum opus. Because Eugenius had been her servant for so long, she offered him her love, admitted him to her Schola Magica to teach him its secrets, and gave him the privilege of publishing an emblematic representation of her sanctuary (which he did in Lumen de Lumine).30) (In this dream she also took a reed he was holding; breaking it, she handed him the shorter piece, which he interpreted as a sign "I shall not live soe long after her, as I have lived with her.") For Rebecca Vaughan to be associated with the divine Thalia—be it for her spirituality or intuitive insights—was high praise indeed. The frequency and character of the dreams involving Rebecca suggest that theirs was an unusually close relationship, not only during the days of their married life but also after her death in her role as familiar spirit through the medium of his dreams.31) Just as the young Welshman who dreamt of swallowing a hawk and was possessed with the gift of poetry, Thomas was given gifts from beyond that made possible his work. Similarly, Henry Vaughan located the source for his own furor poeticus in the sufficiency made possible by the indwelling spirit of God, rather than in his talents alone.

Texas A&M University

Ring out, wild bells, to the wild sky,

Ring out, wild bells, to the wild sky,