“London Snow“

by Robert Bridges

Read by Patricia Klaß Advent Calendar day one

When men were all asleep the snow came flying,

In large white flakes falling on the city brown,

Stealthily and perpetually settling and loosely lying,

Hushing the latest traffic of the drowsy town;

Deadening, muffling, stifling its murmurs failing;

Lazily and incessantly floating down and down:

Silently sifting and veiling road, roof and railing;

Hiding difference, making unevenness even,

Into angles and crevices softly drifting and sailing.

All night it fell, and when full inches seven

It lay in the depth of its uncompacted lightness,

The clouds blew off from a high and frosty heaven;

And all woke earlier for the unaccustomed brightness

Of the winter dawning, the strange unheavenly glare:

The eye marvelled—marvelled at the dazzling whiteness;

The ear hearkened to the stillness of the solemn air;

No sound of wheel rumbling nor of foot falling,

And the busy morning cries came thin and spare.

Then boys I heard, as they went to school, calling,

They gathered up the crystal manna to freeze

Their tongues with tasting, their hands with snowballing;

Or rioted in a drift, plunging up to the knees;

Or peering up from under the white-mossed wonder,

‘O look at the trees!’ they cried, ‘O look at the trees!’

With lessened load a few carts creak and blunder,

Following along the white deserted way,

A country company long dispersed asunder:

When now already the sun, in pale display

Standing by Paul’s high dome, spread forth below

His sparkling beams, and awoke the stir of the day.

For now doors open, and war is waged with the snow;

And trains of sombre men, past tale of number,

Tread long brown paths, as toward their toil they go:

But even for them awhile no cares encumber

Their minds diverted; the daily word is unspoken,

The daily thoughts of labour and sorrow slumber

At the sight of the beauty that greets them, for the charm they have broken.

“…wonders and meruayles of a swerde that was taken out of a stone by the sayd Arthur” from Le Morte Darthur (1485)

by Sir Thomas Malory

Read by Laurie Atkinson adventcal_02

The text below is from Sir Thomas Malory, Le Morte Darthur (Wesminster: William Caxton, 1485), sigs a3v-a4v; a lightly modernised version can be read in Sir Thomas Malory, Le Morte Darthur, ed. Helen Cooper (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998), pp. 8-11, available online at https://archive.org/details/lemortedarthurwi0000malo_q2n3/page/8/mode/2up.

Thenne stood the reame in grete ieopardy long whyle / for euery lord that was myghty of men maade hym stronge / and many wende to haue ben kyng / Thenne Merlyn wente to the archebisshop of Caunterbury / and counceilled hym for to sende for alle the lordes of the reame / and alle the gentilmen of armes that they shold to london come by Cristmas vpon payne of cursynge / And for this cause that Ieshu that was borne on that nyghte that he wold of his grete mercy shewe some myracle / as he was come to be kynge of mankynde for to shewe somme myracle who shold be rightwys kynge of this reame / So the Archebisshop by the aduys of Merlyn send for alle the lordes and gentilmen of armes that they shold come by crystmasse euen vnto london / And many of hem made hem clene of her lyf that her prayer myghte be the more acceptable vnto god / Soo in the grettest chirch of london whether it were Powlis or not the Frensshe booke maketh no mencyon / alle the estates were longe or day in the chirche for to praye / And whan matyns and the first masse was done / there was sene in the chircheyard ayenst the hyhe aulter a grete stone four square lyke vnto a marbel stone / And in myddes therof was lyke an Anuylde of stele a foot on hyghe / and theryn stack a fayre swerd naked by the poynt / and letters / there were wryten in gold aboute the swerd that saiden thus / who so pulleth oute this swerd of this stone and anuyld / is rightwys kynge borne of all Enlond / Thenne the peple merueilled and told it to the Archebisshop I commande said tharchebisshop that ye kepe yow within your chirche / and pray vnto god still that no man touche the suerd tyll the hyhe masse be all done / So whan all masses were done all the lordes wente to beholde the stone and the swerd / And whan they sawe the scripture / som assayed suche as wold haue ben kyng / But none myght stere the swerd nor meue hit He is not here said the Archebisshop that shall encheue the swerd but doubte not god will make hym knowen / But this is my counceill said the archebisshop / that we lete puruey x knyʒtes men of good fame / and they to kepe this swerd / so it was ordeydeyned / and thenne ther was made a crye / that euery man shold assay that wold for to wynne the swerd / And vpon newe yeersday the barons lete maake a Iustes and a tournement / that alle knyʒtes shat wold Iuste or tourneye / there myʒt playe / and all this was ordeyned for to kepe the lordes to gyders and the comyns / for the Archebisshop trusted / that god wold make hym knowe that shold wynne the swerd / So vpon newe yeresday whan the seruyce was done / the barons rode vnto the feld / some to Iuste / and som to torney / and so it happed that syre Ector that had grete lyuelode aboute london rode vnto the Iustes / and with hym rode syr kaynus his sone and yong Arthur that was hys nourisshed broder / and syr kay was made knyʒt at al halowmas afore So as they rode to the Iustes ward / sir kay had lost his suerd for he had lefte it at his faders lodgyng / and so he prayd yong Arthur for to ryde for his swerd / I wyll wel said Arthur / and rode fast after that swerd / and whan he cam home / the lady and al were out to see the Ioustyng / thenne was Arthur wroth and saide to hym self / I will ryde to the chircheyard / and take the swerd with me that stycketh in the stone / for my broder sir kay shal not be without a swerd this day / so whan he cam to the chircheyard sir Arthur aliʒt and tayed his hors to the style / and so he wente to the tent / and found no knyʒtes there / for they were atte Iustyng and so he handled the swerd by the handels / and liʒtly and fiersly pulled it out of the stone / and took his hors and rode his way vntyll he came to his broder sir kay / and delyuerd hym the swerd / and as sone as sir kay saw the swerd he wist wel it was the swerd of the stone / and so he rode to his fader syr Ector / and said / sire / loo here is the swerd of the stone / wherfor I must be kyng of thys land / when syre Ector beheld the swerd / he retorned ageyne and cam to the chirche / and there they aliʒte al thre / and wente in to the chirche / And anon he made sir kay to swere vpon a book / how he came to that swerd / Syr said sir kay by my broder Arthur for he brought it to me / how gate ye this swerd said sir Ector to Arthur / sir I will telle you when I cam home for my broders swerd / I fond no body at home to delyuer me his swerd And so I thought my broder syr kay shold not be swerdles and so I cam hyder egerly and pulled it out of the stone withoute ony payn / found ye ony knyʒtes about this swerd seid sir ector Nay said Arthur / Now said sir Ector to Arthur I vnderstande ye must be kynge of this land / wherfore I / sayd Arthur and for what cause / Sire saide Ector / for god wille haue hit soo for ther shold neuer man haue drawen oute this swerde / but he that shal be rightwys kyng of this land / Now lete me see whether ye can putte the swerd ther as it was / and pulle hit oute ageyne / that is no maystry said Arthur / and soo he put it in the stone / therwith alle Sir Ector assayed to pulle oute the swerd and faylled

Capitulum sextum

Now assay said Syre Ector vnto Syre kay / And anon he pulled at the swerd with alle his myghte / but it wold not be / Now shal ye assay said Syre Ector to Arthur I wyll wel said Arthur and pulled it out easily / And ther with alle Syre Ector knelyd doune to the erthe and Syre Kay / Allas said Arthur myne own dere fader and broder why knole ye to me / Nay nay my lord Arthur / it is not so I was neuer your fader nor of your blood / but I wote wel ye are of an hyher blood than I wende ye were / And thenne Syre Ector told hym all how he was bitaken hym for to nourisshe hym And by whoos commandement / and by Merlyns delyueraunce ¶ Thenne Arthur made grete doole whan he vnderstood that Syre Ector was not his fader / Sir said Ector vnto Arthur woll ye be my good and gracious lord when ye are kyng / els were I to blame said arthur for ye are the man in the world that I am most be holdyng to / and my good lady and moder your wyf that as wel as her owne hath fostred me and kepte / And yf euer hit be goddes will that I be kynge as ye say / ye shall desyre of me what I may doo / and I shalle not faille yow / god forbede I shold faille yow / Sir said Sire Ector / I will aske no more of yow / but that ye wille make my sone your foster broder Syre Kay Seuceall of alle your landes / That shalle be done said Arthur / and more by the feith of my body that neuer man shalle haue that office but he whyle he and I lyue / There with all they wente vnto the Archebisshop / and told hym how the swerd was encheued / and by whome / and on twelfth day alle the barons cam thyder / and to assay to take the swerd who that wold assay / But there afore hem alle ther myghte none take it out but Arthur

“To a Wreath of Snow”

by Emily Brontë

Read by Eva Marik

adventcal_03

O transient voyager of heaven!

O silent sign of winter skies!

What adverse wind thy sail has driven

To dungeons where a prisoner lies?

Methinks the hands that shut the sun

So sternly from this morning′s brow

Might still their rebel task have done

And checked a thing so frail as thou.

They would have done it had they known

The talisman that dwelt in thee,

For all the suns that ever shone

Have never been so kind to me!

For many a week, and many a day

My heart was weighed with sinking gloom

When morning rose in mourning grey

And faintly lit my prison room

But angel like, when I awoke,

Thy silvery form, so soft and fair

Shining through darkness, sweetly spoke

Of cloudy skies and mountains bare;

The dearest to a mountaineer

Who, all life long has loved the snow

That crowned his native summits drear,

Better, than greenest plains below.

And voiceless, soulless, messenger

Thy presence waked a thrilling tone

That comforts me while thou art here

And will sustain when thou art gone

“Winter: My Secret“

by Christina Rossetti

Read by Luisa Stihl

adventcal_04

I tell my secret? No indeed, not I:

Perhaps some day, who knows?

But not to-day; it froze, and blows and snows,

And you’re too curious: fie!

You want to hear it? well:

Only, my secret’s mine, and I won’t tell.

Or, after all, perhaps there’s none:

Suppose there is no secret after all,

But only just my fun.

To-day’s a nipping day, a biting day;

In which one wants a shawl,

A veil, a cloak, and other wraps:

I cannot ope to everyone who taps,

And let the draughts come whistling thro’ my hall;

Come bounding and surrounding me,

Come buffeting, astounding me,

Nipping and clipping through my wraps and all.

I wear my mask for warmth: who ever shows

His nose to Russian snows

To be pecked at by every wind that blows?

You would not peck? I thank you for good will,

Believe, but leave the truth untested still.

Spring’s an expansive time: yet I don’t trust

March with its peck of dust,

Nor April with its rainbow-crowned brief showers,

Nor even May, whose flowers

One frost may wither thro’ the sunless hours.

Perhaps some languid summer day,

When drowsy birds sing less and less,

And golden fruit is ripening to excess,

If there’s not too much sun nor too much cloud,

And the warm wind is neither still nor loud,

Perhaps my secret I may say,

Or you may guess.

“Ring Out, Wild Bells“, from In Memoriam A.H.H.

by Alfred, Lord Tennyson

Read by Andrew Edmonds

adventcal_05

Ring out, wild bells, to the wild sky,

Ring out, wild bells, to the wild sky,

The flying cloud, the frosty light:

The year is dying in the night;

Ring out, wild bells, and let him die.

Ring out the old, ring in the new,

Ring, happy bells, across the snow:

The year is going, let him go;

Ring out the false, ring in the true.

Ring out the grief that saps the mind

For those that here we see no more;

Ring out the feud of rich and poor,

Ring in redress to all mankind.

Ring out a slowly dying cause,

And ancient forms of party strife;

Ring in the nobler modes of life,

With sweeter manners, purer laws.

Ring out the want, the care, the sin,

The faithless coldness of the times;

Ring out, ring out my mournful rhymes

But ring the fuller minstrel in.

Ring out false pride in place and blood,

The civic slander and the spite;

Ring in the love of truth and right,

Ring in the common love of good.

Ring out old shapes of foul disease;

Ring out the narrowing lust of gold;

Ring out the thousand wars of old,

Ring in the thousand years of peace.

Ring in the valiant man and free,

The larger heart, the kindlier hand;

Ring out the darkness of the land,

Ring in the Christ that is to be.

“Annunciation” and “Nativity”

by John Donne

Read by Alexander Edmonds

adventcal_06

Annunciation

Salvation to all that will is nigh;

That All, which always is all everywhere,

Which cannot sin, and yet all sins must bear,

Which cannot die, yet cannot choose but die,

Lo, faithful virgin, yields Himself to lie

In prison, in thy womb; and though He there

Can take no sin, nor thou give, yet He will wear,

Taken from thence, flesh, which death\’s force may try.

Ere by the spheres time was created, thou

Wast in His mind, who is thy Son and Brother;

Whom thou conceivst, conceived; yea thou art now

Thy Maker\’s maker, and thy Father\’s mother;

Thou hast light in dark, and shutst in little room,

Immensity cloistered in thy dear womb.

Nativity

Immensity cloistered in thy dear womb,

Now leaves His well-belov\’d imprisonment,

There He hath made Himself to His intent

Weak enough, now into the world to come;

But O, for thee, for Him, hath the inn no room?

Yet lay Him in this stall, and from the Orient,

Stars and wise men will travel to prevent

The effect of Herod\’s jealous general doom.

Seest thou, my soul, with thy faith\’s eyes, how He

Which fills all place, yet none holds Him, doth lie?

Was not His pity towards thee wondrous high,

That would have need to be pitied by thee?

Kiss Him, and with Him into Egypt go,

With His kind mother, who partakes thy woe.

“Frost at Midnight“

by Samuel Taylor Coleridge

Read by Mehmet Özdemir

adventcal_07

The Frost performs its secret ministry,

Unhelped by any wind. The owlet’s cry

Came loud—and hark, again! loud as before.

The inmates of my cottage, all at rest,

Have left me to that solitude, which suits

Abstruser musings: save that at my side

My cradled infant slumbers peacefully.

’Tis calm indeed! so calm, that it disturbs

And vexes meditation with its strange

And extreme silentness. Sea, hill, and wood,

This populous village! Sea, and hill, and wood,

With all the numberless goings-on of life,

Inaudible as dreams! the thin blue flame

Lies on my low-burnt fire, and quivers not;

Only that film, which fluttered on the grate,

Still flutters there, the sole unquiet thing.

Methinks, its motion in this hush of nature

Gives it dim sympathies with me who live,

Making it a companionable form,

Whose puny flaps and freaks the idling Spirit

By its own moods interprets, every where

Echo or mirror seeking of itself,

And makes a toy of Thought.

But O! how oft,

How oft, at school, with most believing mind,

Presageful, have I gazed upon the bars,

To watch that fluttering stranger ! and as oft

With unclosed lids, already had I dreamt

Of my sweet birth-place, and the old church-tower,

Whose bells, the poor man’s only music, rang

From morn to evening, all the hot Fair-day,

So sweetly, that they stirred and haunted me

With a wild pleasure, falling on mine ear

Most like articulate sounds of things to come!

So gazed I, till the soothing things, I dreamt,

Lulled me to sleep, and sleep prolonged my dreams!

And so I brooded all the following morn,

Awed by the stern preceptor’s face, mine eye

Fixed with mock study on my swimming book:

Save if the door half opened, and I snatched

A hasty glance, and still my heart leaped up,

For still I hoped to see the stranger’s face,

Townsman, or aunt, or sister more beloved,

My play-mate when we both were clothed alike!

Dear Babe, that sleepest cradled by my side,

Whose gentle breathings, heard in this deep calm,

Fill up the intersperséd vacancies

And momentary pauses of the thought!

My babe so beautiful! it thrills my heart

With tender gladness, thus to look at thee,

And think that thou shalt learn far other lore,

And in far other scenes! For I was reared

In the great city, pent ’mid cloisters dim,

And saw nought lovely but the sky and stars.

But thou, my babe! shalt wander like a breeze

By lakes and sandy shores, beneath the crags

Of ancient mountain, and beneath the clouds,

Which image in their bulk both lakes and shores

And mountain crags: so shalt thou see and hear

The lovely shapes and sounds intelligible

Of that eternal language, which thy God

Utters, who from eternity doth teach

Himself in all, and all things in himself.

Great universal Teacher! he shall mould

Thy spirit, and by giving make it ask.

Therefore all seasons shall be sweet to thee,

Whether the summer clothe the general earth

With greenness, or the redbreast sit and sing

Betwixt the tufts of snow on the bare branch

Of mossy apple-tree, while the nigh thatch

Smokes in the sun-thaw; whether the eave-drops fall

Heard only in the trances of the blast,

Or if the secret ministry of frost

Shall hang them up in silent icicles,

Quietly shining to the quiet Moon.

From Hamlet, 1.1.

by William Shakespeare

Read by ‘Dumbshow’ (aka. Jonathan Sharp, Robert McColl, and Hanno Dorneich)

adventcal_08

As found on: https://shakespeare.mit.edu/hamlet/hamlet.1.1.html

HORATIO

That can I;

At least, the whisper goes so. Our last king,

Whose image even but now appear’d to us,

Was, as you know, by Fortinbras of Norway,

Thereto prick’d on by a most emulate pride,

Dared to the combat; in which our valiant Hamlet–

For so this side of our known world esteem’d him–

Did slay this Fortinbras; who by a seal’d compact,

Well ratified by law and heraldry,

Did forfeit, with his life, all those his lands

Which he stood seized of, to the conqueror:

Against the which, a moiety competent

Was gaged by our king; which had return’d

To the inheritance of Fortinbras,

Had he been vanquisher; as, by the same covenant,

And carriage of the article design’d,

His fell to Hamlet. Now, sir, young Fortinbras,

Of unimproved mettle hot and full,

Hath in the skirts of Norway here and there

Shark’d up a list of lawless resolutes,

For food and diet, to some enterprise

That hath a stomach in’t; which is no other–

As it doth well appear unto our state–

But to recover of us, by strong hand

And terms compulsatory, those foresaid lands

So by his father lost: and this, I take it,

Is the main motive of our preparations,

The source of this our watch and the chief head

Of this post-haste and romage in the land.

BERNARDO

I think it be no other but e’en so:

Well may it sort that this portentous figure

Comes armed through our watch; so like the king

That was and is the question of these wars.

HORATIO

A mote it is to trouble the mind’s eye.

In the most high and palmy state of Rome,

A little ere the mightiest Julius fell,

The graves stood tenantless and the sheeted dead

Did squeak and gibber in the Roman streets:

As stars with trains of fire and dews of blood,

Disasters in the sun; and the moist star

Upon whose influence Neptune’s empire stands

Was sick almost to doomsday with eclipse:

And even the like precurse of fierce events,

As harbingers preceding still the fates

And prologue to the omen coming on,

Have heaven and earth together demonstrated

Unto our climatures and countrymen.–

But soft, behold! lo, where it comes again!

Re-enter Ghost

I’ll cross it, though it blast me. Stay, illusion!

If thou hast any sound, or use of voice,

Speak to me:

If there be any good thing to be done,

That may to thee do ease and grace to me,

Speak to me:

Cock crows

If thou art privy to thy country’s fate,

Which, happily, foreknowing may avoid, O, speak!

Or if thou hast uphoarded in thy life

Extorted treasure in the womb of earth,

For which, they say, you spirits oft walk in death,

Speak of it: stay, and speak! Stop it, Marcellus.

MARCELLUS

Shall I strike at it with my partisan?

HORATIO

Do, if it will not stand.

BERNARDO

’Tis here!

HORATIO

’Tis here!

MARCELLUS

’Tis gone!

Exit Ghost

We do it wrong, being so majestical,

To offer it the show of violence;

For it is, as the air, invulnerable,

And our vain blows malicious mockery.

BERNARDO

It was about to speak, when the cock crew.

HORATIO

And then it started like a guilty thing

Upon a fearful summons. I have heard,

The cock, that is the trumpet to the morn,

Doth with his lofty and shrill-sounding throat

Awake the god of day; and, at his warning,

Whether in sea or fire, in earth or air,

The extravagant and erring spirit hies

To his confine: and of the truth herein

This present object made probation.

MARCELLUS

It faded on the crowing of the cock.

Some say that ever ’gainst that season comes

Wherein our Saviour’s birth is celebrated,

The bird of dawning singeth all night long:

And then, they say, no spirit dares stir abroad;

The nights are wholesome; then no planets strike,

No fairy takes, nor witch hath power to charm,

So hallow’d and so gracious is the time.

HORATIO

So have I heard and do in part believe it.

But, look, the morn, in russet mantle clad,

Walks o’er the dew of yon high eastward hill:

Break we our watch up; and by my advice,

Let us impart what we have seen to-night

Unto young Hamlet; for, upon my life,

This spirit, dumb to us, will speak to him.

Do you consent we shall acquaint him with it,

As needful in our loves, fitting our duty?

MARCELLUS

Let’s do’t, I pray; and I this morning know

Where we shall find him most conveniently.

Exeunt

“The Gift“

by William Carlos Williams

Read by Patricia Klaß

adventcal_09

As the wise men of old brought gifts

guided by a star

to the humble birthplace

of the god of love,

the devils

as an old print shows

retreated in confusion.

What could a baby know

of gold ornaments

or frankincense and myrrh,

of priestly robes

and devout genuflections?

But the imagination

knows all stories

before they are told

and knows the truth of this one

past all defection

The rich gifts

so unsuitable for a child

though devoutly proffered,

stood for all that love can bring.

The men were old

how could they know

of a mother’s needs

or a child’s

appetite?

But as they kneeled

the child was fed.

They saw it

and

gave praise!

A miracle

had taken place,

hard gold to love,

a mother’s milk!

before

their wondering eyes.

The ass brayed

the cattle lowed.

It was their nature.

All men by their nature give praise.

It is all

they can do.

The very devils

by their flight give praise.

What is death,

beside this?

Nothing. The wise men

came with gifts

and bowed down

to worship

this perfection.

“The House of Christmas”

by G. K. Chesterton

Read by Amanda Vernon

adventcal_10

There fared a mother driven forth

Out of an inn to roam;

In the place where she was homeless

All men are at home.

The crazy stable close at hand,

With shaking timber and shifting sand,

Grew a stronger thing to abide and stand

Than the square stones of Rome.

For men are homesick in their homes,

And strangers under the sun,

And they lay on their heads in a foreign land

Whenever the day is done.

Here we have battle and blazing eyes,

And chance and honour and high surprise,

But our homes are under miraculous skies

Where the yule tale was begun.

A Child in a foul stable,

Where the beasts feed and foam;

Only where He was homeless

Are you and I at home;

We have hands that fashion and heads that know,

But our hearts we lost – how long ago!

In a place no chart nor ship can show

Under the sky’s dome.

This world is wild as an old wives’ tale,

And strange the plain things are,

The earth is enough and the air is enough

For our wonder and our war;

But our rest is as far as the fire-drake swings

And our peace is put in impossible things

Where clashed and thundered unthinkable wings

Round an incredible star.

To an open house in the evening

Home shall men come,

To an older place than Eden

And a taller town than Rome.

To the end of the way of the wandering star,

To the things that cannot be and that are,

To the place where God was homeless

And all men are at home.

From “A Christmas Tree”

by Charles Dickens

Read by Nikki Berger

adventcal_11

As found at https://short-stories.co/@charlesdickens/a-christmas-tree-qpkv58eqvr91

There is probably a smell of roasted chestnuts and other good comfortable things all the time, for we are telling Winter Stories– Ghost Stories, or more shame for us–round the Christmas fire; and we have never stirred, except to draw a little nearer to it. But, no matter for that. We came to the house, and it is an old house, full of great chimneys where wood is burnt on ancient dogs upon the hearth, and grim portraits (some of them with grim legends, too) lower distrustfully from the oaken panels of the walls. We are a middle-aged nobleman, and we make a generous supper with our host and hostess and their guests–it being Christmas-time, and the old house full of company–and then we go to bed. Our room is a very old room. It is hung with tapestry. We don’t like the portrait of a cavalier in green, over the fireplace. There are great black beams in the ceiling, and there is a great black bedstead, supported at the foot by two great black figures, who seem to have come off a couple of tombs in the old baronial church in the park, for our particular accommodation. But, we are not a superstitious nobleman, and we don’t mind. Well! we dismiss our servant, lock the door, and sit before the fire in our dressing-gown, musing about a great many things. At length we go to bed. Well! we can’t sleep. We toss and tumble, and can’t sleep. The embers on the hearth burn fitfully and make the room look ghostly. We can’t help peeping out over the counterpane, at the two black figures and the cavalier–that wicked- looking cavalier–in green. In the flickering light they seem to advance and retire: which, though we are not by any means a superstitious nobleman, is not agreeable. Well! we get nervous– more and more nervous. We say \”This is very foolish, but we can’t stand this; we’ll pretend to be ill, and knock up somebody.\” Well! we are just going to do it, when the locked door opens, and there comes in a young woman, deadly pale, and with long fair hair, who glides to the fire, and sits down in the chair we have left there, wringing her hands. Then, we notice that her clothes are wet. Our tongue cleaves to the roof of our mouth, and we can’t speak; but, we observe her accurately. Her clothes are wet; her long hair is dabbled with moist mud; she is dressed in the fashion of two hundred years ago; and she has at her girdle a bunch of rusty keys. Well! there she sits, and we can’t even faint, we are in such a state about it. Presently she gets up, and tries all the locks in the room with the rusty keys, which won’t fit one of them; then, she fixes her eyes on the portrait of the cavalier in green, and says, in a low, terrible voice, \”The stags know it!\” After that, she wrings her hands again, passes the bedside, and goes out at the door. We hurry on our dressing-gown, seize our pistols (we always travel with pistols), and are following, when we find the door locked. We turn the key, look out into the dark gallery; no one there. We wander away, and try to find our servant. Can’t be done. We pace the gallery till daybreak; then return to our deserted room, fall asleep, and are awakened by our servant (nothing ever haunts him) and the shining sun. Well! we make a wretched breakfast, and all the company say we look queer. After breakfast, we go over the house with our host, and then we take him to the portrait of the cavalier in green, and then it all comes out. He was false to a young housekeeper once attached to that family, and famous for her beauty, who drowned herself in a pond, and whose body was discovered, after a long time, because the stags refused to drink of the water. Since which, it has been whispered that she traverses the house at midnight (but goes especially to that room where the cavalier in green was wont to sleep), trying the old locks with the rusty keys. Well! we tell our host of what we have seen, and a shade comes over his features, and he begs it may be hushed up; and so it is. But, it’s all true; and we said so, before we died (we are dead now) to many responsible people.

“Christmas aboard the Endurance” from South: The Endurance Expedition

by Sir Ernest Shackleton

Read by Jonathan Sharp

adventcal_12

As found at https://www.gutenberg.org/files/5199/5199-h/5199-h.htm

Heavy floes held up the ship from midnight till 6 a.m. on December 25, Christmas Day. Then they opened a little and we made progress till 11.30 a.m., when the leads closed again. We had encountered good leads and workable ice during the early part of the night, and the noon observation showed that our run for the twenty-four hours was the best since we entered the pack a fortnight earlier. We had made 71 miles S. 4° W. The ice held us up till the evening, and then we were able to follow some leads for a couple of hours before the tightly packed floes and the increasing wind compelled a stop. The celebration of Christmas was not forgotten. Grog was served at midnight to all on deck. There was grog again at breakfast, for the benefit of those who had been in their bunks at midnight. Lees had decorated the wardroom with flags and had a little Christmas present for each of us. Some of us had presents from home to open. Later there was a really splendid dinner, consisting of turtle soup, whitebait, jugged hare, Christmas pudding, mince-pies, dates, figs and crystallized fruits, with rum and stout as drinks. In the evening everybody joined in a “sing-song.” Hussey had made a one-stringed violin, on which, in the words of Worsley, he “discoursed quite painlessly.” The wind was increasing to a moderate south-easterly gale and no advance could be made, so we were able to settle down to the enjoyments of the evening.

Excerpt from Sir Gawain and the Green Knight

translated by J.R.R. Tolkien

Read by Hanno Dorneich

adventcal_13

Part I

1. When the siege and the assault had ceased at Troy,

and the fortress fell in flame to firebrands and ashes,

the traitor who the contrivance of treason there fashioned

was tried for his treachery, the most true upon earth –

it was Æneas the noble and his renowned kindred

who then laid under them lands, and lords became

of well-nigh all the wealth in the Western Isles.

When royal Romulus to Rome his road had taken,

in great pomp and pride. He peopled it first,

and named it with his own name that yet now it bears;

Tirius went to Tuscany and towns founded,

Langaberde in Lombardy uplifted halls,

and far over the French flood Felix Brutus

on many a broad bank and brae Britain established

full fair

where strange things, strife and sadness,

at whiles in the land did fare,

and each other grief and gladness

oft fast have followed there.

2. And when fair Britain was founded by this famous lord,

bold men were bred there who in battle rejoiced,

and many a time that betide they troubles aroused.

In this domain more marvels have by men been seen

than in any other that I know of since that olden time;

but of all that here abode in Britain as kings

ever was Arthur most honored, as I have heard men tell.

Wherefore a marvel among men I mean to recall,

a sight strange to see some men have held it,

one of the wildest adventures of the wonders of Arthur.

If you will listen to this lay but a little while now,

I will tell it at once as in town I have heard

it told,

as it is fixed and fettered

in story brave and bold,

thus linked and truly lettered,

as was loved in this land of old.

3. This king lay at Camelot at Christmas-tide

with many a lovely lord, lieges most noble,

indeed of the Table Round all those tried brethren,

amid merriment unmatched and mirth without care.

There tourneyed many a time the trusty knights,

and jousted full joyously these gentle lords;

then to the court they came at carols to play.

5. But Arthur would not eat until all were served;

his youth made him so merry with the moods of a boy,

he liked lighthearted life, so loved he the less

either long to be lying or long to be seated:

so worked on him his young blood and wayward brain.

And another rule moreover was his reason besides

that in pride he had appointed: it pleased him not to eat

upon festival so fair, ere he first were apprised

of some strange story or stirring adventure,

or some moving marvel that he might believe in

of noble men, knighthood, or new adventures;

or a challenger should come a champion seeking

to join with him in jousting, in jeopardy to set

his life against life, each allowing the other

the favor of fortune, were she fairer to him.

This was the king’s custom, wherever his court was holden,

at each famous feast among his fair company

in hall.

So his face doth proud appear,

and he stands up stout and tall,

all young in the New Year;

much mirth he makes with all.

6. Thus there stands up straight the stern king himself,

talking before the high table of trifles courtly.

There good Gawain was set at Guinevere’s side,

with Agravain a la Dure Main on the other side seated,

both their lord’s sister-sons, loyal-hearted knights.

Bishop Baldwin had the honor of the board’s service,

and Iwain Urien’s son ate beside him.

These dined on the dais and daintily fared,

and many a loyal lord below at the long tables.

Then forth came the first course with fanfare of trumpets,

on which many bright banners bravely were hanging;

noise of drums then anew and the noble pipes,

warbling wild and keen, wakened their music,

so that many hearts rose high hearing their playing.

Then forth was brought a feast, fare of the noblest,

multitude of fresh meats on so many dishes

that free places were few in front of the people

to set the silver things full of soups on cloth

so white.

Each lord of his liking there

without lack took with delight:

twelve plates to every pair,

good beer and wine all bright.

7. Now of their service I will say nothing more,

for you are all well aware that no want would there be.

Another noise that was new drew near on a sudden,

so that their lord might have leave at last to take food.

For hardly had the music but a moment ended,

and the first course in the court as was custom been served,

when there passed through the portals a perilous horseman,

the mightiest on middle-earth in measure of height,

from his gorge to his girdle so great and so square,

and his loins and his limbs so long and so huge,

that half a troll upon earth I trow that he was,

but the largest man alive at least I declare him;

and yet the seemliest for his size that could sit on a horse,

for though in back and in breast his body was grim,

both his paunch and his waist were properly slight,

and all his features followed his fashion so gay

in mode:

for at the hue men gaped aghast

in his face and form that showed;

as a fay-man fell he passed,

and green all over glowed.

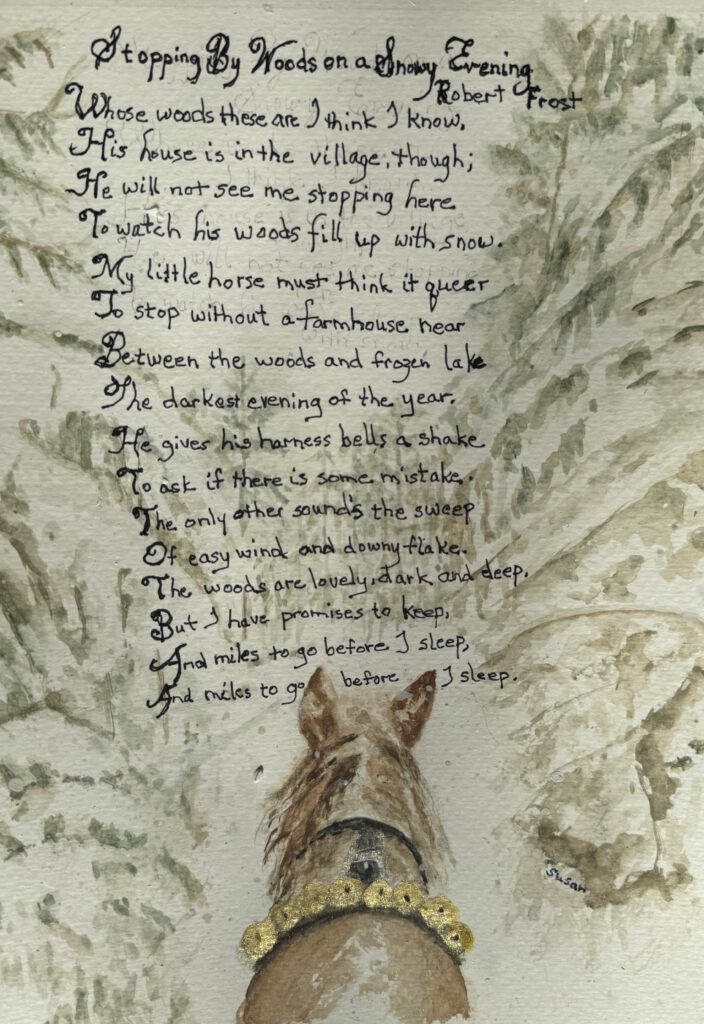

“Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening”

by Robert Frost

Read by Fabienne Peterson

Painting by Susan Holliday

adventcal_14

Robert Frost (1874 – 1963)

Robert Frost, famous American poet, was born in California in 1874. He owned several large farms during his lifetime, where many of his poems are set.

Encouraged by the publication of his first poem at 19, Frost’s poems are famous for their unique conversational writing style, often reflecting Frost’s deep respect for nature. He once explained, “All my poems are love poems”.

Robert Frost was the only poet to have received four prestigious Pulitzer Prizes in his lifetime. He also was nominated several times for the Nobel Prize in Literature.

This is his work “Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening”

Whose woods these are I think I know.

His house is in the village though;

He will not see me stopping here

To watch his woods fill up with snow.

My little horse must think it queer

To stop without a farmhouse near

Between the woods and frozen lake

The darkest evening of the year.

He gives his harness bells a shake

To ask if there is some mistake.

The only other sound’s the sweep

Of easy wind and downy flake.

The woods are lovely, dark and deep,

But I have promises to keep,

And miles to go before I sleep,

And miles to go before I sleep.

“Mistletoe“

by Walter de La Mare

Read by Ann-Sophie Schmidt

adventcal_15

Sitting under the mistletoe

(Pale-green, fairy mistletoe),

One last candle burning low,

All the sleepy dancers gone,

Just one candle burning on,

Shadows lurking everywhere:

Some one came, and kissed me there.

Tired I was; my head would go

Nodding under the mistletoe

(Pale-green, fairy mistletoe),

No footsteps came, no voice, but only,

Just as I sat there, sleepy, lonely,

Stooped in the still and shadowy air

Lips unseen—and kissed me there.

“The Oxen“

by Thomas Hardy

Read by Avi Spencer-Blume

adventcal_16

Christmas Eve, and twelve of the clock.

“Now they are all on their knees,”

An elder said as we sat in a flock

By the embers in hearthside ease.

We pictured the meek mild creatures where

They dwelt in their strawy pen,

Nor did it occur to one of us there

To doubt they were kneeling then.

So fair a fancy few would weave

In these years! Yet, I feel,

If someone said on Christmas Eve,

“Come; see the oxen kneel,

“In the lonely barton by yonder coomb

Our childhood used to know,”

I should go with him in the gloom,

Hoping it might be so.

“Windigo“

by Louise Erdrich

Read by Cuan Olivier

adventcal_17

For Angela

The Windigo is a flesh-eating, wintry demon with a man buried deep inside of it. In some Chippewa stories, a young girl vanquishes this monster by forcing boiling lard down its throat, thereby releasing the human at the core of ice.

You knew I was coming for you, little one,

when the kettle jumped into the fire.

Towels flapped on the hooks,

and the dog crept off, groaning,

to the deepest part of the woods.

In the hackles of dry brush a thin laughter started up.

Mother scolded the food warm and smooth in the pot

and called you to eat.

But I spoke in the cold trees:

New one, I have come for you, child hide and lie still.

The sumac pushed sour red cones through the air.

Copper burned in the raw wood.

You saw me drag toward you.

Oh touch me, I murmured, and licked the soles of your feet.

You dug your hands into my pale, melting fur.

I stole you off, a huge thing in my bristling armor.

Steam rolled from my wintry arms, each leaf shivered

from the bushes we passed

until they stood, naked, spread like the cleaned spines of fish.

Then your warm hands hummed over and shoveled themselves full

of the ice and the snow. I would darken and spill

all night running, until at last morning broke the cold earth

and I carried you home,

a river shaking in the sun.

Ring out, wild bells, to the wild sky,

Ring out, wild bells, to the wild sky,