The Woods, the West, and Icarus's Mother: Myth in the Contemporary American Theatre

John Russell Brown

Published in Connotations Vol. 5.2-3 (1995/96)

In the youthful days of modern Europe, a mythology inherited from the Greek and Roman empires offered a sportive freedom to the mind among pagan gods and goddesses, fabulous creatures and unnatural marvels. A resort to myth enabled writers and other artists to escape from practical problems of everyday life and from the strict patterns of thought which were imposed by religious and political authorities. The early Europeans wrote about the world which they inhabited in ways were expected and prescribed and, in another vein, indulged themselves in another world, reaching for a more personal and private satisfaction. In their fantasies, they aligned themselves with mythical persons through whom they might inhabit a lost civilization, the ruins of which could still be seen.

At the end of the fifteenth century, the fresco painters who adorned the Salone dei Mesi in the Palazzo di Schifanoia in Ferrara, depicted at ground level the powerful d'Este family and the daily life of the city and the farmsteads of the Po basin. They created a series of tableaux, one for each of the various months of a year, and arranged them anticlockwise, starting on the west end of the southern wall: here they depicted the giving and taking of wealth, laboring peasants and attentive lackeys, and the rich and famous, powerful as they sat in thrones or astride great horses. The painters used a second level for the comparatively simple, demonstrative signs of the zodiac, but reserved the topmost and most extensive level for the triumphs of pagan gods. Here they painted fantastic creatures, bridled swans and nibbling rabbits, the delights of Venus and of springtime, vistas of pellucid seas and impossible mountains, dancing, music, and timeless stillness. Here young lovers touch and arouse each other, and share half−dazed and tender [→page 340] looks; Mars kisses Venus, their discarded clothes at the bedside; the Graces pose naked, unselfconsciously for all to see. By depicting the gods known only in pagan myth, the painters were able to show a world both intimate and sensual, and beyond reality.

At the end of the sixteenth century, Shakespeare and his fellow poets in England also used myth to allow a freedom to the mind and to express immediate sensation. This was a means of escaping the boundaries of everyday experience and of prescribed thought. They used words and not paint, and so they did not have to segregate the real from the mythological on separate levels of depiction, or tangible experience from high flights of thought, or dangerous ideas from acceptable dogma. For writers all levels were available at the same time.

Shakespeare's King Richard the Second is keenly aware of the political reasons why he must descend from the top of the castle walls and yet, even in that moment, as he imagines himself feeling his way down a spiral of stone steps in some dark turret, he also sees himself as Phaethon, the sun−god, and feels the horses pulling his chariot as if they were so many restless carthorses:

Down, down I come, like glist'ring Phaeton,

Wanting the manage of unruly jades. (Richard II, III.iii.178−79)

What are Richard's "unruly jades," but his turbulent, irresistible, frightened thoughts, unmanageably dangerous, unprecedented, and experienced with an absolute immediacy? They come to his mind, and so to his spoken words, together with the more fantastic, dazzling, sun−god.

In The Merchant of Venice, waiting to see if the good−looking Bassanio has the intelligence or instinct to choose the right casket and so win her hand in marriage, Shakespeare's helpless Portia thinks instinctively of the sacrificed virgin, Hesione, not naming the victim, but identifying her suitor as "young Alcides" and her attendants as married women with tears and harrowed faces:

I stand for sacrifice;

The rest aloof are the Dardanian wives,

With blearèd visages come forth to view

The issue of th'exploit. (Merchant, III.ii.57−60)

[→page 341] In the back of Portia's mind, there is the "sea−monster" which threatens to devour her, the rock on which she is chained, and the heartless sea, reaching into the distance like her own future at which she is compelled to look. She may also remember that Alcides did not rescue Hesione for love, but merely to win some horses which her father had offered as reward.

It might be argued that classical allusions such as these in Shakespeare's work are the product of a little learning which decorated a moment's dialogue with a small pedantic flourish. In the earliest plays this may sometimes be true, but there the effect is not so poised as in more mature works, the words not so simple, and the effect not so passionate or sensuous.

Modern scholarship can fill out the details of each individual myth, define them, trace their ancestry, and compare one "usage" with another, but this was not the way of the poets of that time. Myth offered them both freedom and immediate sensation, relaxation and adventure, a relief from bracing or restricted thought.

Despite being common in Greek and Latin, the dictionaries tell us that the identifying word myth is not found in English until the eighteen−thirties. In the seventeenth century, Walter Raleigh's History of the World (1614) has mythological, while mythology and mythologize had arrived a few years earlier (cf. OED); the classical myths were present then in many minds, but only as a general attitude of mind, not as a way of thought that could be singular and specific. Other derivatives from myth soon arrived upon the scene: mythic and mythical early on, and then mythographer and mythologic; by the nineteenth century, these were joined by mythoclast and mythomaniac. But in Shakespeare's day, myths had still not earned a word by which to make themselves known individually, one from another: they were malleable and indefinite; only occasionally precise, for a special purpose and moment, as each writer pleased. The "mythical" was anyone's territory, in which creative writers could please themselves.

For the poets, myths were pluralist and fragmentary, vivid as the most intimate of experiences or fantasies, and usable in whatever way they chose. Any mythologic person or place could become a personal treasure, individually experienced, user−friendly, and neither remote nor [→page 342] constrained by rules and demarcations. When Ben Jonson wanted to explain how a poet's imagination could soar to great heights and yet remain in touch with personal experience, he used a trio of myths: a poet, he wrote, has a divine instinct or rapture which

contemns common and known conceptions. It utters somewhat above a mortal mouth… it gets aloft, and flies away with his rider, whither before it was doubtful to ascend. This the poets understood by their Helicon, Pegasus, or Parnassus.1)

* * *

In early modern Europe, the myths of Greece and Rome were an amazing other world, almost out of the reach of thinkers who tried to define everything by Christian doctrine and not easily controlled by the powerful censors of art in all its forms, and especially those of the printed book and performed play. When another new world began to establish itself in North America, artists found it was less easy to use memories of the ancient, "classical" world; the necessary books and learning were not generally available, and the physical remains of that civilization were outside the bounds of most people's mental journeys. Artists had to find some other place in which their imaginations could be at ease and live with heroes and exemplars that would suit their own dissatisfactions and aspirations.

They did not have to look far, because they lived in the midst of an unknowable world of huge trees in woods and forests uncropped by man; and if they did not live within sight of broad rivers, greater in size than any known from earlier days in Europe, they might well be within the sound of them or have heard their fathers and strangers speak of crossing them. Here was a world that they could people with myths of their own making, and as the settlers moved out of the woods, travelling towards the West, the strange otherness of the vast prairie and desert would serve the same need. These were kingdoms fit for imagined heroes and monsters; and they are still territories of the mind in North America. Dramatists enter such other worlds more than other writers perhaps, because they must strive all the time to give substance to their thoughts in persons and in action, rather than in words alone, [→page 343] arranged in sentences for readers: they need mythical heroes and exploits when they wish to place on stage what cannot be seen in ordinary life.

The snag was—and it still is—that these other worlds of woods and wild west had very few gods or heroes associated with them, no earlier literature or portraiture, no ruins of palaces or populous cities. Writers had to invent their own mythological creatures, and these have not proved to be a strong breed, seldom lasting for more than a generation of writers except as nameless types or shadowy projections of real−life persons. So while Phaethon does not whip his steeds and Hesione does not stand ready for sacrifice in recent American theatre, there are new myths, as they are made and then forgotten or cheapened, and used in much the same way as those of the Renaissance.

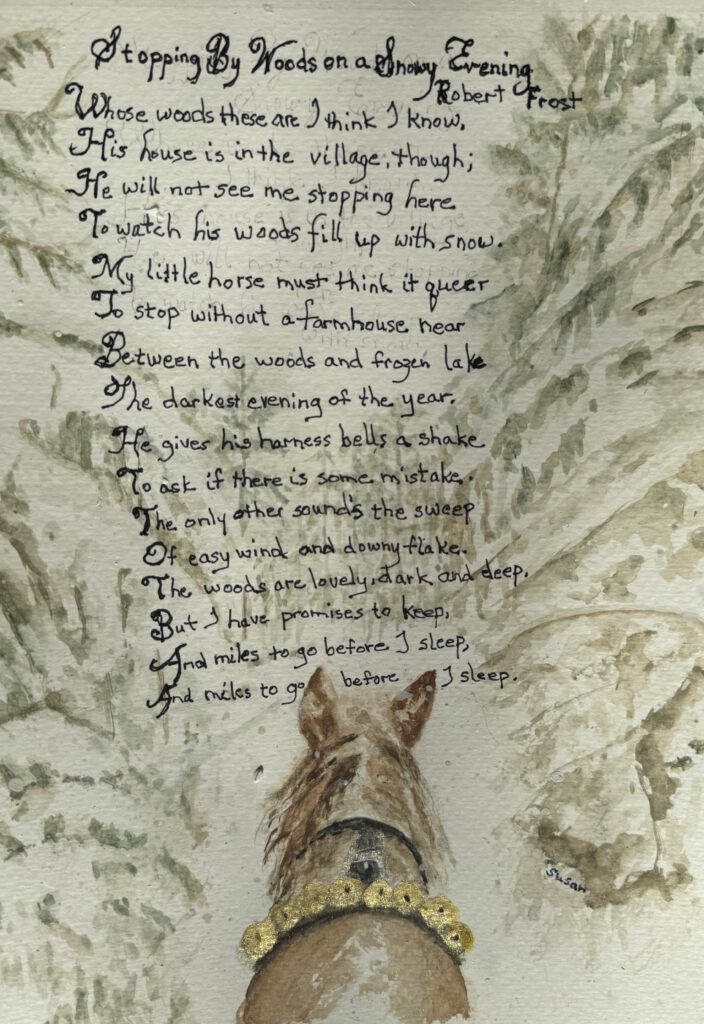

In David Mamet's The Woods (1977) Nick brings Ruth to a cabin in northern Michigan for a weekend and the play begins with the two sitting on the porch. Here myth−making starts playfully, and even comically, as Ruth does her best to fill the sky with heroes:

These seagulls they were up there, one of them was up there by himself.

He didn't want the other ones.

They came, he'd flap and get them off.

He let this one guy stay up there a minute.

NICK Tell me.

RUTH They flew off.

Pause.

NICK We have a lot of them. And herons.2)

Nick and Ruth cannot share each other's stories for long: practicalities and differences intrude. However, Nick has been to these woods many times before and has developed for himself more frightening, less ordinary myths, inaccessible to other persons. There is Herman Waltz, a fellow soldier with his father in the second World War:

He thought his head was a radio. He had had dental work and said that Hitler told him things about his wife. Things he should do to her. He later killed himself. (25)

Nick's mind is full of persons who are strange and separable from life, more demanding and more giving. He imagined that some one would [→page 344] say to him "Let us be lovers… . I know who you are… . I know what you are" (94). This event would take place outside the city, in the woods where he and Ruth now sit together.

Some of his inventions are Vikings and Martians; others are nameless creatures, more demanding and frightening, and associated with a black hole and with fire:

I see the window, and the shades are blowing. There has come a breeze, and all the curtains blow. They are on fire.

It laps around the window. On all sides.

Someone is calling my name. Nicholas.

I swear to you.

I hear them in a voice unlike a man or woman. When I look, I do not want to know. I know that there is something there. I look I see a bear. A bear has come back. At the window. Do you hear me, Ruth?

Do you know what this is? To crawl beneath my house. This house is mine now. In its hole it calls me. In the Earth. (Pause.) Nicholas.

He's standing upright. On his legs. He has a huge erection. I am singed. He speaks a human language, Ruth. I know. He has these thoughts and they are trapped inside his mouth. His jaw cannot move. (96−97)

David Mamet has studied ancient drama at university and so, as he peoples the woods for his character's sake, he reaches back to classical myths of Orestes and Oedipus, even though he does not use their names; his myths are, however, the same stories of inheritance, darkness, dynasties, fire, and mysteries. Ruth tells Nick "You read too many books" (94), as if Mamet felt a need to apologize for the literary sources for these stories of the Woods invented for his mythologizer or mythomaniac.

Myth from the classics and renaissance drama is given a wider function in this play as its very action takes on the shape of earlier stories, by Sophocles and Shakespeare. Nick at the edge of the water, having forced himself on Ruth during a thunderstorm—perhaps having tried to kill her—and now feeling totally alone and ready to take his own life, asks with Lear "Am I insane?" and with Orestes he cries out "I have seen it all come back." His utterance comes close to screaming:

What are we doing here? What are we doing here?

Pause.

[→page 345] What will happen to us? We can't know ourselves… . How can we know ourselves?

I have to leave. (99)

Nicholas becomes his author's mythical hero, experiencing in the freedom of mythic invention an alienation from the world and his own actions.

In contrast, Mamet's American Buffalo (1975) is set firmly in the city away from the forests and the myths awakened by its strangeness. Don's Resale Shop is grounded in the world from which all its junk has come, and it is occupied by three persons who are at home in the city. The action of the play involves routines of daily life, together with crime, cheating, and the lure of wealth. However, the play's title is the name of a rare nickel coin, long since out of circulation, and alludes unmistakably to a magnificent indigenous creature once common in the West. It suggests a mythological escape which most of the time is unregarded by those who try to obtain possession of the coin and cash in on its rareity, and that of other coins they think are hoarded somewhere in the city. It is the means whereby, at moments of extreme drama, the myths of early America come to the surface of consciousness to be expressed in dialogue and action, attracting attention and defining thoughts which are otherwise dismissed or not registered at all.

Thinking of the wealth the American Buffalo might bring if they can steal it, Teach starts talking about earlier times and the "wilderness" of the West:

TEACH You know what is free enterprize?

DON No. What?

TEACH The freedom …

DON … yeah?

TEACH Of the Individual.

DON … yeah?

TEACH To Embark on Any Fucking Course that he sees fit.

[The capitalized "Embark" might indicate a mythic value for this word.]

DON Uh−huh …

TEACH In order to secure his honest chance to make a profit. Am I so out of line on this?

DON No.

TEACH Does this make me a Commie?

DON No.

[→page 346] TEACH The country's founded on this, Don. You know this

. [Now the myths of pioneer days are more strongly in mind, and Don backs away.]

DON Did you get a chance to take a nap?

TEACH Nap nap nap nap nap. Big deal.

DON (Pause) Yeah.

TEACH Without this we're just savage shitheads in the wilderness.

DON Yeah.

TEACH Sitting around some vicious campfire.3)

The men in the wilderness of the early West can be savage and vicious, as well as heroes embarking on a course to claim a well−founded freedom: for Teach, a mythic world has polarized thought and quickened passion beyond his ordinary abilities.

Other objects amongst the junk force consciousness back to this primitive and distant way of life. When a "pig iron" is found, Don identifies it as "a thing that they stick in dead pigs keep their legs apart all the blood runs out" (35). This stops the conversation for no more than a nod of recognition but, some time later in the following Act, an attempt to talk about a dream of freedom shows that thought, in that short silence, did indeed go back to brutality in the rural West. At the end of the play, Teach trashes the junk shop with this same pig iron. As he does so he mourns in savage rage for a powerful myth of trust and friendship, a lost world from the days of the buffalo, and of a still earlier world of "cavemen": "The Whole Entire World. ⁄ There Is No Law. ⁄ There Is No Right And Wrong. ⁄ The World Is Lies. ⁄ There Is No Friendship. ⁄ Every Fucking Thing. ⁄ Pause. ⁄ Every God−Forsaken Thing… . We all live like cavemen" (103). Soon Teach is speaking of himself as the heroic cowboy in some endless, lonely shoot−out: "I went out on a limb for you… . I go out there. I'm out there every day." But the old myth does not hold any longer; for him it is a hopeless confrontation, as Teach knows to his own loss: "There is nothing out there… I fuck myself" (103−04).

In American Buffalo, as in The Woods, David Mamet has used myths taken from the Woods and West for plays which are in all other ways grounded in the present time. The myths are not remembered casually or incidentally; they are used to define the central theme and the most [→page 347] powerful moments of dramatic action, and to take his play into far reaches of his mind.

* * *

Of the same generation as Mamet, Sam Shepard is a dramatist who has moved more openly into a mythic world, as if aware that only its terrain could offer the kind of life he wished to affirm. The West is where his characters feel strongest or, at least, most sure of their feelings: it is not surprizing to hear from a friend that Sam had sat and "watched six straight hours of silent cowboy reruns."4) True West (1980) is set in present−day reality, in southern California, close to the desert. Two brothers, Lee and Austin, are soon talking of "The Forefathers," seeing them in a mythic world, with "Candlelight burning into the night" as they take their rest in "Cabins in the wilderness" (6). They become engaged in writing an old−style Western, even though they accept that few have been made since "Lonely Are the Brave," with Kirk Douglas. Austin, the younger brother, despises their movie, even as he is writing it:

It's a bullshit story! It's idioic. Two Lamebrains chasing each other across Texas! Are you kidding? Who do you think's going to go see a film like that?5)

Yet they do write it and it is to the desert wilderness that they both instinctively want to go to "think" and to recover some sanity and peace.

"There's no such thing as the West any more!" Austin tells Saul, the movie director: "It's a dead issue! It's dried up, Saul, and so are you" (35). But nevertheless the mythical idea of it sustains their deepest thoughts and passions. Eventually the two brothers wreck the home and fight in rivalry as their astonished mother makes off to check into a motel. Their struggle is violent and savage, leading, it seems, to Lee being strangled to death with a telephone cord. But that is not the end: he was shamming death, and the play moves at last into the mode of the now mythic West. The playscript ends with a stage direction drawn from a silent cowboy movie:

[→page 348] They square off to each other, keeping a distance between them. Pause, a single coyote heard in distance, lights fade softly into moonlight, the figures of the brothers now appear to be caught in a vast desert−like landscape, they are very still but watchful for the next move, lights go slowly to black as the after−image of the brothers pulses in the dark, coyote fades.

Shepard takes to myths as if needing to breathe their freer air. While the West recurs in many plays, he is by no means restricted in choice. He searches out new myths and even, in a bookish way, ransacks classical and renaissance stories for heroes and marvels to hold attention and give his imagination scope. Angel City (1976) uses the modern way of life associated with the name of L. A., and Hollywood films and their stars; but into this world, enters Rabbit, the medicine−man with various Indian charms, a cross between Marlowe's Faustus and Mephostophilis. In fact, Rabbit Brown has no special powers but, because others seem to believe in them, he seldom questions that he can do what is required of him. Merely by talking about what he will do, he offers visions to his potential paymasters which show the nature of their desires, just as Christopher Marlowe's Faustus did:

Yeah, but what if we could come up with a character that nobody's ever seen before. Something in flesh and blood. Not just an idea but something so incredible that as soon as they came in contact with it they'd pass out or go into convulsions or something. That's what they're looking for.6)

In a much earlier play,7) Shepard started the action by bringing on stage a bunch of apparently unremarkable people intent on having a barbecue picnic near a beach, but when they see a vapor−trailing, acrobatic jet airplane, which might be skywriting, they are taken up with the pilot's other−worldly exploits. Bill yells, "Get our of our area!" but soon the two women try to establish contact with him, both claiming to be his wife:

PAT Come on, sweetie! Where have you been?

JILL We've been waiting and waiting! (31)

The pilot flies off and the party breaks up. But the pilot still holds attention and takes the picnickers out of their usual world. Howard and [→page 349] Bill, left alone, effect some smoke signals from the barbecue as if trying to bring the pilot back to their base−camp in a desert. The women return with wild tales of the pilot's new exploits which they assume to have been for their gratification. Frank returns, as "in a daze," and announces that he has seen the pilot crashing his machine into the water with a sound and splash of gigantic dimensions:

The water goes up to fifteen hundred feet and smashes the trees, and the firemen come… . And the pilot bobbing in the very centre of a ring of fire that's closing in. His white helmet bobbing up and bobbing down… . (44−46)

The noise of an off−stage crowd becomes deafening, showing that the strangest action is taking place off−stage; soon only Howard and Bill are left, standing very still, as Jill goes off again, calling out "you guys are missing out" (45).

Shepard has used an ancient myth to reflect upon the very ordinary occasion of a picnic. By providing an equivalent of Icarus's flight towards the sun, he has provoked not only wonder, but also a concern about the nature of what is ordinary and unexamined. The title of the play, Icarus's Mother, alerts the audience to ask questions: this person never appears on stage and no one speaks of her. Perhaps this trick title owes something to Jan Breughel who composed his well−known painting of Icarus with attention drawn to the foregrounded figure of a ploughman, absorbed in earth−bound toil. As W. H. Auden wrote, a viewer will inevitably consider that:

the ploughman may

Have heard the splash, the forsaken cry,

But for him it was not an important failure.8)

Shepard has retold the myth and repositioned it in the consciousness of his audience by leaving Icarus offstage and by choosing a title that positively makes an audience think about a long chain of events and choices leading up to this incident. The myth is used for its own sake, as a story of aspiration, and also to show the nature of its fall−out among apparently ordinary persons. Everyone, except perhaps the two competitive and secretive men, has found, in the horror of the pilot's [→page 350] death, an object of awe which is beautiful, pure, and invincible; and so his exploits expose the picnickers in their less daring lives and smaller aspirations.

Shepard has not used the myth in a pedantic way, setting it down as he might have found it in books or paintings. In his play, a new Icarus is present with the excitement and flush of a new disovery, not incidental to the dramatist's purpose, but seeming rather to direct it. The ancient myth has lifted Shepard out of "common and known conceptions," so that he rises aloft and seems to be flying, as if on Pegasus, and taking his audience with him.

The title of Shepard's latest play, Simpatico (1995), suggests no mythic tale, but a focus on intimate and unforced personal relations. Realistically set in a world of horse−racing, betting, cheating, blackmail, marital tensions, and financial success and failure, it is enlivened not by heroes and amazing exploits, but by drunkness, petty crime, and a shameful sexual act, photographed some years before the play's action begins. Here myth is used in the more incidental manner which was common in Renaissance plays; but nevertheless it is crucial in the development of the drama, highlighting and illuminating the moment when the two most honest characters come to trust each other in a tarnished and sinister world.

Cecilia tries to explain why she loves the Kentucky Derby, a race she has never attended:

Yes. It was foolish to get suckered in by something like that but—I love the Derby. I've always—I—I remember being in London. It rained all the time. Always raining. And I—I would stay in and watch the races. I remember watching that big red horse—That magnificient red horse. What was his name? He was on the news. Everybody knew his name.

SIMMS Secretariat.

CECILIA Yes! That's the one. Secretariat. And he won by miles that day. Twenty lengths or something.

SIMMS Thirty−one.

CECILIA Yes. Thirty−one lengths. It was incredible. I've never seen an animal like that. As though he was flying.

SIMMS He was.

CECILIA He was like that winged horse they used to have on the gas stations, you know—That red, winged horse.

[→page 351] SIMMS Pegasus.

CECILIA Yes! Just like Pegasus. Ever since then I've dreamed of going to the Derby.

SIMMS That wasn't the Derby you were watching. That was the Belmont.9)

The classical myth is not introduced to make a learned point: the play is too up−front and irregular in form to support such an idea. Rather Pegasus opens up a moment of sympathy and trust by insisting on the marvellous and on a shared moment of recognition: seen on Mobil gas stations, Pegasus is like an illumination in the sky, out of this world and yet a matter of everyday familiarity.

Shepard does not consider myths to be remote from ordinary life and the product of bookish learning. Rather they provide a way of sustaining and presenting the most intense and charged personal feelings. In Motel Chronicles (San Francisco: City Lights Books, 1982) he collected a series of short autobiographical memoirs, and in this very personal book, myth repeatedly makes an entrance. The very first item is the narrator's recollection of suffering from toothache as a child and being carried at night by his mother to a place in the prairie where huge plaster dinosaurs were "standing around in a circle." He tells how he was carried around these giant statues, through their legs and under their bellies, and found himself "Staring up at the teeth of Tyranosaurus Rex." Except for the little blue lights that they had for eyes, it was the king of them all, the huge tyrant, that was the culminating image still living from this moment of past time. Among the photographs of family groups, favourite cars, and familiar places, that were provided for this book by Shepard's friend Johnny Dark, is one different from all the rest, simpler and overtly dramatic: it is of the Mobil Gas Pegasus, rearing off towards the right of the page against a glowing sky (113).

Later in Motel Chronicles, in an item dated November 23, 1981, Shepard tells in the third person of being in a truck almost exactly halfway between San Francisco and L. A. The driver stopped and, crawling under a fence, went to the middle of a field to sit cross−legged while the "raw smell of cattle filled his chest" and the sun was setting with clouds "like giant hawk wings." The narrator is very close to this person because he knows that he wanted to talk to himself, but was stopped by "the stillness of space." Thinking of the two great cities lying to north and [→page 352] south made him want to stay there, but already "things were pulling him in two directions." It was just then that an impossible levitation seemed to occur:

A huge hand grabbed him from behind. A hand without a body. It carried him up, miles above the highway. He didn't fight. He'd lost the fear of falling. The hand went straight through his back and grabbed his heart. It didn't squeeze. It was a grip of pure love. He let his body drop and watched it tumble without hope. His heart stayed high, tucked in the knuckles of a giant fist. (121)

A myth is here being re−formed in the mind, stemming directly out of immediate sensation.

* * *

Shepard and Mamet are not alone in the acceptance of myth as a means of engaging ambitiously in a theatre that is more often grounded in the presentation of the here and now. Shepard tells a story in Motel Chronicles of acting in a film for which he had to get up at 5:30 a.m. and be driven to a trailer home in open country where he changed into clothes very like his own—"Maybe a little bit stiffer. Cleaner maybe too"—so that he "wondered if he was supposed to be playing himself." He stared out at the highway on which he would be filmed as he drove a motorcycle behind the camera car and, in this world of make−believe, Shepard notices two people who were entirely caught up in a world of myth: as he "slid into the back seat of a grey Cadillac," he became fascinated by two actors who were "talking feverishly about Greek Drama. They kept it up for miles" (10). This was not casual talk: these people, Shepard realized, spoke about Greek myths to "indicate to each other their deep convictions," trying perhaps to share the farthest reaches their minds could go.

Occasionally the use of myth in American Theatre is unmistakable, usually when a classic story is borrowed or characters are formed along clearly defined lines. So it is in Eugene O'Neill's Mourning Becomes Electra (1931) or Elizabeth Egloff's The Swan (1987), which retells the story of Jupiter's arrival as a swan. But even the more literary borrowings usually [→page 353] work more covertly, as with the "unmotivated" appearances of the Boatman who is Charon in Len Jenkin's Poor Folk's Pleasure (1989) and, in the same play, with Frankie the Finn whose message is repeated in a language no one can understand. Sometimes historical events are remembered with only the faintest reference to actual facts, but with a mythological resonance: as for example, in the singing of the "British Grenadiers" and the end of Richard Nelson's New England (1994) or the repeated allusion to the attainment of freedom for Columbia in the same author's Life Sentences (1993). In some plays, such as Eric Overmeyer's On the Verge or Paula Vogel's Baltimore Waltz (1991), a multitude of mythological wonders follow each other in quick succession, showing the bewilderment arising from extraordinary feeling rather than an achievement of it.

In all this, American dramatists use myths as their predecessors have done, but what is perhaps new is a consciousness of the transience of these devices. They sometimes have a single classical basis, but they also come from an environment that is peculiarly American: the Woods and the West, and an estrangement from the classical inheritance even while being fascinated by it. Some writers approach myths with great caution and share that caution with their audiences; others approach with mockery or with daring; some cannot manage without pomposity or solemn seriousness. The common feature is a desire to share intuitions about the nature and the possibilities of the world about them, and of themselves. Myths are not a reassuring bedrock of a shared imagination; they are used for occasional forays into the unusual, the unknown, the extravagant thoughts which demand recognition, the intensely personal reaction, and the personal reaction that in some way suggests a more than isolated resonance. The use of myths is not the most notable feature of American theatre, but attention to their occurrence will often lead a critic to the imaginative centre of a play and reveal to directors, designers, and actors how a production should move beyond a reflection of the ordinary.

University of Michigan

Ann Arbor

Ring out, wild bells, to the wild sky,

Ring out, wild bells, to the wild sky,