Kinship and the River Cam: George Herbert’s Anthropocentrism Reconsidered

Sarah Crover

Published in Connotations Vol. 33 (2024)

Abstract

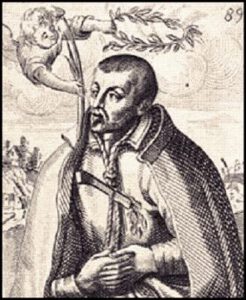

George Herbert’s devotional poetry, with its minute attention to the natural world, ought to be well suited to early modern scholars with an ecocritical bent. However, his work is frequently dismissed as disappointingly anthropocentric or simply as a poor fit for ecological readings of the early modern literary canon. With a few exceptions, a more egalitarian reading of Herbert’s engagement with nature has been largely resisted. This article aims to address this lack and reexamine Herbert’s relationship with nature. I read Herbert’s writing as revealing an investment in a flatter ontological hierarchy than he is usually given credit for. While the debate about how much agency Herbert is willing to ascribe to the nonhuman in his poetry continues, little time has been spent comparing this work with his engagement with the natural world in his prose letters. Specifically, four Latin letters protesting the proposed drainage of the River Cam in 1620 merit more attention than they have received in this debate and may help, I suggest, clarify his position since they provide insight into how he applied his thinking in practice, not just in theory. Ultimately, Herbert’s anthropocentric engagement with the natural world is nuanced by his figuring of the relationship between humans and nature as one of familial kinship.

George Herbert’s devotional poetry, with its minute attention to the natural world, ought to be well suited to early modern scholars with an [→ page 160] ecocritical bent. However, his work is frequently dismissed as disappointingly anthropocentric (see, for example, Borlik; Fudge; and Ralph) or simply as a poor fit for ecological readings of the early modern literary canon and passed over with only a glancing reference in discussions of nature writers of the period. Even those who are willing to give Herbert the benefit of the doubt tend to assume his engagement with nonhuman nature is limited by a classically influenced Christian worldview that significantly subordinates nature to humans on the scala naturae (see Bushnell). With a few exceptions (see, for instance, Glimp; Zane Calhoun Johnson; and Remien), a more egalitarian reading of Herbert’s engagement with nature has been largely resisted. This article aims to address this lack and reexamine Herbert’s relationship with nature. Without intending to wholly discount ecocritical critiques, I read Herbert’s work as revealing an investment in a flatter ontological hierarchy than he is usually given credit for. While the debate about just what degree of agency Herbert is willing to ascribe to the nonhuman in his poetry continues, little time has been spent comparing this work with his engagement with the natural world in his prose letters. Specifically, four Latin letters protesting the proposed drainage of the River Cam (hereafter “Cam”) in 1620, written during his time as Cambridge’s Public Orator, merit more attention than they have received in this debate and may help, I suggest, clarify his position since they provide insight into how he applied his thinking in practice, not just in theory.1

This article is a companion piece to the four other essays (by Angela Balla, Katie Calloway, Paul Dyck, and Debra Rienstra) in this debate on “George Herbert and Nature” in Connotations: we come to different conclusions, but each of us reexamines Herbertian conceptions of nature.2 While not primarily ecological in focus, these other essays support, as mine does, a more nuanced vision of Herbert’s supposed anthropocentricism. My primary focus is on Herbert’s Latin letters and the insight they give into his practical application of his beliefs; however, I join the others in drawing upon samples of his devotional poetry, “Providence” and “Man,” to make my case. [→ page 161]

Although the relationship between humans and God remains firmly at the centre of Herbert’s universe, I contend that his anthropocentric engagement with the natural world is nuanced by his figuring of the relationship between humans and nature as one of familial kinship—a hierarchical family, true, but still a family where every member owes a necessary duty of care to the other. In both his devotional poetry and his letters as Public Orator, Herbert’s language conveys a vision of shared responsibility for correct preservation of nature. This kind of biblically motivated “good steward” model is not unique, but it does complicate received wisdom about Herbert as a nature writer. No matter how paternal in structure, a kin relationship necessitates a view that the natural world is owed something in return for its service. Moreover, such a framing of reciprocal duty shared among humans and nature as coparticipants in a family is unusual (though not unheard of) among the early modern intelligentsia.3 When viewed side by side, Herbert’s poems “Providence” and “Man” articulate more clearly what is only touched upon in his letters regarding the Cam: that God’s created world is owed good stewardship and pastoral care by its human “high Priests” (“Providence” l. 13) in recognition of its shared kinship with humanity.

The Clergyman and the Critics

The question of where Herbert stands on the position of humanity in the natural world is a vexed one. Scholars often struggle to reconcile his apparent anthropocentricism with his keen attention to and obvious respect for the minutiae of nonhuman creation. Perhaps for this reason, Herbert is not a favourite choice when it comes to ecocritical studies of early modern nature writing.4 As Peter Remien notes, “Herbert has not been the subject of much ecocritical inquiry, [though] scholars have long noted the ‘ecological’ dynamics of ‘Providence’” (116).5 Those who do directly engage with his work can be quite dismissive. Laura Ralph notes that Herbert’s nature poetry “reasserts the prevailing framework [of anthropocentricism] without question” (23), while Todd Borlik, in [→ page 162] his ecocritical anthology Literature and Nature in the English Renaissance, introduces the Herbert entry by calling him “outrageously anthropocentric,” referring to his devotional poetry as “radiat[ing] a sense of being miraculously at home in a bespoke world where everything has been designed for human comfort and delight” (“George Herbert” 70).6 Borlik does modulate this position elsewhere in the same text, acknowledging that works like Herbert’s “Providence” which “envision nature as a holy temple seem to articulate—albeit with a theological rather than an ecological vocabulary—a commandment to see and treat the environment more holistically” (15), but the disappointment in the aside—“theological rather than ecological vocabulary”—is unmistakable.

Even when they are not dismissing Herbert, ecocritically minded scholars frequently are tepid in their acknowledgements. In “Renaissance Literature and the Environment,” Borlik allows that “[d]evotional poets such as George Herbert might regard other creatures as humanity’s servants, yet the belief that Providence operated within the environment could foster an intimation of ecological principles” (n.p.). This provisional endorsement gives the overall sense that any Herbertian gestures towards a more inclusive engagement with nature are more accidental than intentional. Similarly, Rebecca Bushnell, in speaking of the Western tradition generally, notes that, while belief in “human exceptionalism and supremacy over all other living things” was commonplace, the deep entanglement of humans in the natural world always undermined that sense of privilege” (3).7 In other words, it is material reality that forces these thinkers to question their anthropocentricism, not their own ideological inclinations. While Bushnell does not mention Herbert directly in this quotation, she may well have him in mind as one of these thinkers. In her anthology section titled “Plants” (where she includes Herbert’s poem “Rose”), Bushnell observes,

premodern cultures attributed to plants astonishing powers, expressed in the notion of a plant’s “virtues,” omnipresent in early natural history, herbal medicine, and magic […]. According to the Oxford English Dictionary, “virtue” may denote “the power inherent in a thing; […] for plants, a virtue is then “power to affect the body in a beneficial manner; strengthening, sustaining, [→ page 163] or healing power.” The key word here is power, granting plants a form of agency expressed through action in animal bodies. (73-74)

Again, Bushnell suggests that, despite being preconditioned towards anthropocentricism, early modern writers like Herbert did have the capacity to assign a kind of agency to nonhuman creatures that would seem to challenge that human exceptionalism, but they rarely did so.

There are some notable exceptions to this reading of Herbert’s engagement with nonhuman creation. David Glimp points out that Herbert’s creatures in “Providence” are more than mere obedient servants to man and ultimately “take on a conciliar function, and guide the poet’s own writing. Devotion originates not with mankind, but with the advice of the created world” (126). Peter Remien, building upon Glimp’s version of a more egalitarian Herbert, notes that his “attentiveness to the creature leads to a quasi-sublime rapture before the creature” (114) and suggests “the collective oeconomy established by the nonhuman creation supplies Herbert with a model of divine government superior to human life” (115).8 Glimp and Remien thus allow for a Herbert who is enraptured by and seeks lessons from the natural world, rather than simply relegating it to the status of obedient human tool. Similarly, Zane Calhoun Johnson suggests that in “Man” Herbert envisions a kind of benevolent entanglement “between the human body and its environment” (128). Challenging accusations of Herbert’s supposed extreme anthropocentricism, Johnson argues that his positive version of human and environmental enmeshment at least makes space for a beneficial, shared ecological relationship (129-30). On this subject, Ken Hiltner observes,

George Herbert considers the far-reaching implications of losing indigenous species: “More servants wait on man / Than he’ll take notice of; in ev’ry path / He treads down that which doth befriend him, / When sickness makes him pale and wan.” Herbert’s point is that even the seemingly insignificant plants we marginalize might well be the “herbs [that] gladly cure our flesh” in time of sickness. (144) [→ page 164]

Hiltner notes a deep concern for the natural world in “Man,” above and beyond its usefulness to us, as peopled with friends who are overlooked and “tread[] down” by “man.” However, he stops short of acknowledging an impulse in Herbert to push back against anthropocentric cosmologies.

Curiously, for a text on environmental protest literature in the period, Hiltner does not discuss Herbert’s own protest letters about the proposed alterations to the Cam: he is either unaware of or uninterested in this application of theory to practice, and, indeed, none of the previously discussed authors make reference to these letters either. For the most part, these authors merely focus on a smattering of Herbert’s most obviously nature-oriented poems (such as “Providence” and “Man”) and overlook his prose writing. The impression forms that he is “outrageously anthropocentric” with occasional glimmers of broad-mindedness, which, I argue, falls far short of a balanced understanding of Herbert’s ecological engagement.

Defending the Cam

George Herbert’s opposition to the draining of the River Cam was practical and economical, as we will see, but a second look reveals less mercenary concerns as well. In the early seventeenth century, the Crown was considering a project to drain the fens feeding the Cam and Ouse. As Catherine Freis and Greg Miller note, “King James hoped to decrease the flooding common to the low-lying area and increase its agricultural productivity and had appointed two agents to oversee the project, which did not move forward until after his reign” (Introduction vi). George Herbert, and other Cambridge loyalists, vehemently opposed the project’s potential impact on the Cam, which flows through the city and the university. Herbert was Cambridge’s Public Orator during this period,9 so he was well-placed to protest this plan, and several of his letters regarding this matter survive. In his capacity as Public Orator, “Herbert solicit[ed] the aid of the powerful on behalf of Cambridge University against those [who supported the project.] Herbert [→ page 165] and his colleagues feared the result would be to lower the water level of the river, making transportation of goods and people far more difficult, or impossible” (vi).10 A meeting of the Privy Council was held on the proposed draining, “led by the King, on April 11, 1620, attended by Greville, Naunton, and representatives of Cambridge University and the town” (Freis and Miller, “Notes” 126). Ultimately the project collapsed because an agreement could not be reached between the Commissioners and the undertakers (see Hutchinson 605, qtd. in Freis and Miller, “Notes” 126), and those against the draining celebrated a temporary victory (the project was carried out in fits and starts from 1625 onward, although it was not completed until the 1650s; see Ash 14).11 It is during this period, after April 1620, that four Latin letters were written by Herbert, all titled gratiae de fluevio, i.e. thanks concerning the river. Recorded in The Orator’s Book (see Freis and Miller, “Notes” 127), Herbert thanks various powerful figures, including the meeting attendees, for the preservation of the river.12

Herbert’s letter to James I is the most circumspect, but still gives a clear sense of his/Cambridge’s opposition. Since the King himself originally supported the project, Herbert’s expressions of relief at the project’s failure necessitated careful phrasing. His letter to James already emphasizes in its heading that his thanks is regarding the river and “against the contractors” (gratiae de fluuio contra Redemptores, Herbert “[To King James]” 44), suggesting he is taking pains to avoid any implication that he is criticizing the king.13 This specification of subject matter is absent in the titles of his other three letters. After the salutation and appropriate opening flattery and obeisance, Herbert thanks the King for gifting Cambridge the Cam, implying that rather than the project collapsing, James offered those opposed to the project a clear “triumph” by acknowledging the rightness of their position: “your most humble subjects […] celebrate a triumph when we are given a whole River by our King” (44).14

Herbert is more direct in his letters to friends and colleagues Francis Bacon, Fulke Greville,15 and Robert Naunton.16 While not implicating [→ page 166] James, his descriptions of the other proponents of the project are scathing. In Letter Six, to Robert Naunton, Secretary of State, Herbert thanks him for preserving the Cam from would-be fen drainers, calling them “Xerxeses” and “Scourgers of the seas” (51).17 He is alluding here to Xerxes’ retaliation against waters of the Hellespont, for drowning his bridge, by ordering them to be scourged with 300 lashes.18 Herbert then deliberately conflates the drying out of the land and potential lowering of river levels (which would affect the Cam’s navigability and the university’s status as a cultural and trade hub) with the drying up of the knowledge the Cambridge “muses” thirst for.19 He makes a similar case to Francis Bacon in Letter Five,20 congratulating him on his success in defending the navigability of the river by “grind[in[g] into powder” their enemies (49).21 Playing on the adage that “a dry soul is wisest,” he notes that without Bacon’s assistance Cambridge was in danger of becoming so dry that its scholars would “not [be] so much wise as out-of-the-way philosophers” (47).22 In his flamboyant praise of Bacon, Naunton, and Greville, for having scotched the project, he makes their support a question of loyalty to the Alma Mater, congratulating them on considering Cambridge as a mother and they her sons who cannot tolerate the drying up of the riverine breasts from which they have formerly drunk, and saying they have done well to pay their debt. It should be noted that, while these men were instrumental in scuttling the plan, there can be no certainty that they were wholly opposed to the draining of the fens in general or altering the Cam in particular. As Freis and Miller note (see “Notes” 126), the letter to James appears to be more of an exercise in attempting to stave off future draining projects than acknowledging strong support in blocking the project. Even his framing of the project’s failure to launch as a kingly gift of the river to Cambridge implies an intentional transaction, which, while a very optimistic interpretation of events, is also a clear-eyed massaging of facts that wrongfoots the king should he attempt to withdraw his supposed gift. Herbert’s words to his peers similarly read like an exhortation to remember their duty to their Alma Mater rather than an acknowledgement of a shared goal. Repeatedly he thanks them for their support of [→ page 167] their “Nurturing Mother” (Herbert, “Ad R. Naunton” 51). He places no period on this support: he asks Greville to “keep up the good work” of defending the river (53).23 The kinship ties he establishes between alumni and the university are as enduring, he seems to suggest, as the kinship ties of flesh and blood. In Herbert’s representation of the matter, a failure to prevent the project would amount to a familial betrayal of both the river and university. These letters present a masterful guilt trip that aims to forestall any backsliding; for who, as Herbert says, “would be able to tolerate the dry nipples and parched breasts of such a noble parent without a sense of distress?” (“Ad R. Naunton” 51).24

While Herbert’s elegant political maneuvering reveals considerable artistry, especially a talent for painting a verbal picture, it is his treatment of the Cam as kin that is most revealing for the purposes of this paper. His rhetorical treatment of the parties involved in this dispute as tyrants or heroes may seem to pursue a reductive line of reasoning, but when he moves to discussing the debts owed to the interested nonhuman parties—the university and the river—he displays a surprisingly nuanced vision, particularly for a thinker who has been accused of displaying a “rigidly hierarchical anthropocentricism” in his poetry (Fudge 3-4, qtd. in Glimp 195). Herbert refers to Cambridge university using the conventional term for one’s home university, the Alma Mater or “Nourishing Mother,” but then intensifies the kinship association by extending the metaphor to the graduates and beneficiaries of the university by calling them her “sons” in his letter to Naunton (51). Cambridge becomes their “noble parent” and nurse from whose breasts they “drank” (51).25 In elaborating on the conceit, Herbert subordinates the humans to the human-created and human-serving institution in the familial hierarchy. Then he further extends the metaphor, and the network of kinship, to the Cam. By praising Cambridge’s “sons” for keeping “Those Springs, from which they themselves once drank, intact for her” (“Ad R. Naunton” 51), he makes the metonymic link between river Cam and Cambridge, and metaphorically links them both to knowledge, depicting the river as the inextricable and critical milk or [→ page 168] life blood of the larger institutional body, which is elevated in importance above those “sons” by “for her.” Thus, the Cam is as much kin, as a part of the whole, as Cambridge is. This envisioned kinship, while anthropomorphic, disrupts the traditional hierarchal structure of the chain of being, since it arguably places the needs of two nonhuman entities on equal footing with those of the humans they serve. Herbert’s framing of the relationship calls to mind the fifth commandment, which requires children to honour their parents (see Exod. 20:12). In all but his letter to James, Herbert emphasizes duty and service of sons to their mother university, and he takes care each time to make the river an inseparable part of that mother. The river may figure as an instrumental good in his letter, but by strategically framing it as part of Alma Mater, he is able to argue that it holds a place of critical intrinsic worth amongst its “sons,” and is therefore owed the respect and obedience usually reserved for human kin. This was not the only rhetorical move available to Herbert.26 He could just as easily have chosen to emphasize how the God-given river was meant to serve humans, and that this project represented a misguided stewardship of an important resource, or that its careful taming to the hand of man would be squandered—these kinds of metaphors are readily available and frequently employed in the same period in discussions of other rivers, such as the Thames. For instance, Edmund Spenser describes the London Thames in Book Three of the Faerie Queene (1590) as a wild horse that only the English can master. The Thames is controlled by Troynovant (proto-London), who has subdued him: “Vpon [Thames’] stubborne neck whereat he raues / With roring rage, and sore him selfe does throng, / That all men feare to tempt his billowes strong, / She fastned hath her foot” (3.11.45.3-6).27 This brutal depiction of breaking the river into service, by placing its neck under the English capital’s heel, precludes mutual love and service, much less kinship. William Camden, in his chorographic poem De Connubio Tamae et Isis, is less violent in his figurations, but his description of the river leaves no room for misunderstanding the natural world’s subordination to humanity. Interleaved through his prose work [→ page 169] Britannia (1610), De Connubio has the personified river offer homage to Elizabeth I. While describing the geographic location of the royal castle of Windsor on the banks of the river, Thames pauses: “therewith Tamis seeming to bow his knee, / And gently crouch, obeisance made, and then he thus went on,” continuing his praise of the queen (Camden 289-90).28 Camden thus makes a topographical fact (that the castle is situated on a river bend) serve as evidence of the river’s willing subordination to and service of the crown, and, by extension, the English people. Herbert would certainly be aware of these and other characterizations of English rivers, but they do not appear to influence his own rhetorical approach. Instead, he refuses these options and insists upon a model where a familial relationship and reciprocal duty between human and nonhuman parties is envisioned.

Besides emphasizing our kinship with the Cam by prescribing filial duties to her, Herbert also argues that contractors aiming to drain the fens and alter the Cam embody a kind of overstepping or theft of the duties of other natural bodies and weather systems, such as the sun and droughts. His letter to Greville claims that the contractors are “stealing the sun’s job” (53),29 and his letter to Bacon likewise suggests that the contractors seek to “illegally” (47) drain the waters.30 In Herbert’s world view, human interventions that alter the rivers and fens from their appointed state are an unsanctioned and even criminal enterprise. He describes recent droughts as having “scoffed” at the plan and done “more than a thousand contractors could” (47).31 The sun and the drought are allowable intervenors, carrying out a “job”; humans are stepping outside the hierarchal chain of service and throwing things out of balance.32 This figuration of human and non-human actors as squabbling over their duties is reminiscent of a large unruly family; it also deliberately blurs boundaries between human and nonhuman creatures, yet again challenging the popular notion of a Herbertian cosmology where humans stand firmly separate from and above the rest of creation.

Leaning into his watery conceit, Herbert dissolves boundaries in another way. In each of his letters, Herbert moves seamlessly between the [→ page 170] literal river and the metaphorical one. As his words make clear, he means both that they have literally drunk the river waters, and that they have drunk the knowledge supplied from Mother Cambridge, and that neither one can survive with the proposed changes to the river. He laments, “No reasonable person doubts that without water and short on provisions, the colleges would be abandoned, and the Muses’ marvelous abodes like forgotten widows, or sapless and withered trees, would be stripped of her foster sons” (“Ad R. Naunton” 51).33 At once pragmatic and hyperbolic, Herbert blends mundane concerns of bodily nourishment and commerce (the river would still be the most reliable thoroughfare for trade and transportation in this era), with the more ethereal concerns of knowledge acquisition and spiritual nourishment. A true university man, he is acutely aware that the two go hand in hand: one kind of drinking is impossible without the other. Each time, he deftly reminds the reader of familial ties: the loss of the river, he argues, would be equivalent to destruction of the college, and the college/river would become like “forgotten widows” (51). That he is thinking of both the university and the Cam when he describes these widowed, “marvelous abodes” of muses is clear because he uses this metaphor again in his letter to James, where he reminds him that rivers in general, and a university river in particular, are places they delight in and inhabit. While thanking his king for the gift of the river, in his perhaps most pointed statement to James, he observes, “since [the muses] once delighted in Rivers, you now bestow upon us the waters they inhabit!” (45).34 Muse, river, university, and man are all kin and should be treated accordingly. Even a king should not break up a family.

As Freis and Miller point out, “we find in [Herbert’s letters] many tropes and habits of mind that are also evident in his English and Latin poems” (Introduction vi). This echoing of habits and tropes suggests we can draw from them a sense of how he was thinking about the natural world in general, and the River Cam more specifically. These letters reveal two key insights about Herbert’s habit of mind. The first is the choice of metaphor: as I have already discussed above, Herbert [→ page 171] chooses to figure the Cam and Cambridge as parts of the same, critically important nourishing motherly body, even though he had other, well-recognized, figurative options available to him. The second is the way this argument, making humankind owe loyalty and service to the University/river (rather than the other way around), might be seen by those who style Herbert as entirely anthropocentric as an odd subversion of his usual stance. However, upon closer inspection, that sense of loyalty and care is also present in “Man” and “Providence,” and it is to this point I turn now, by way of conclusion.

Herbert’s Creaturely Kin in His Devotional Poetry

“Providence” and “Man” are two poems that are frequently used to indict Herbert for subordinating creation, but they merit a second look. It cannot be said that he avoids entirely the trap of paternalism or anthropocentrism, but it is only fair, in light of his letters, to reexamine what we believe we know about Herbert as a thinker and poet. An in-depth exploration of his devotional poems is outside the scope of this paper, but I will touch upon them here briefly to illustrate how well their preoccupations dovetail with the ideas expressed in his letters.

At first glance, his poem “Providence” presents a straightforward styling of the natural world as subordinate to humans. For example, the speaker asserts that

Man is the worlds high Priest: he doth present

The sacrifice for all; while they below

Unto the service mutter an assent,

Such as springs use that fall, and windes that blow.

(l.13-16)

This figuration could suggest that, while not without some agency, the rest of nature are the obedient congregants who are left to “mutter assent” to the higher prayers and wisdom of the priestly Man. However, these lines can be interpreted another way. Rienstra, on the one hand, [→ page 172] notes that, while “Providence” makes clear distinctions between human and animal identity, it “subtly question[s] a simple view of human superiority” (148), and “Man” moves from a comfortable sense of “human superiority” to the “last two stanzas […] [which] hint[] that human superiority is not automatic” and can be “squandered” (149). Dyck, on the other hand, comments, “[t]he boldness of Herbert’s declaration of human priesthood is necessary because that rule constitutes the imperative to listen and receive” (273). Calloway traces the influence of Lucretius and particularly Epicurean atomism in Herbert’s development of a theology of nature more inclusive than that proposed by Aristotle (see 115). Finally, Balla, in exploring Herbert’s great intellectual debt to Gerson, highlights Gerson’s ascription of “intrinsic spiritual significance” to all creatures that is mirrored at least in the conclusion of “Providence” (311). She notes that the speaker ultimately “leans toward Christian kinship” (307) with the rest of creation.

Like my co-contributors, I see more space for fellowship among creatures than strict hierarchy in this poem. While Man may be the high priest and favourite beneficiary of nature’s wealth, Herbert makes clear that this bounty should not be abused, nor the care unreciprocated. In “Providence,” he pointedly notes,

Bees work for man; and yet they never bruise

Their masters flower, but leave it, having done,

As fair as ever, and as fit to use;

So both the flower doth stay, and hony run.

Sheep eat the grasse, and dung the ground for more:

Trees after bearing drop their leaves for soil:

(l.65-70)

The consistent theme is one of reciprocity and balance: never take too much, do not befoul your resources, use nature’s gifts with due care. This position chimes nicely with his styling of the Cam as part of a motherly body that deserves respect and protection. While this approach is not unproblematic, Herbert seems to take quite seriously both the powers and duties of humanity.35 In a time where hierarchy was [→ page 173] usually viewed as a positive and natural structure, a benevolent patriarch who takes seriously his responsibility to look after his human and environmental kin is at least several steps away from the “outrageous” anthropocentrism of which he is accused. Moreover, his styling of Man as “high Priest” bears careful consideration. From a modern and secular perspective this term can take on a more negative valence than it would for Herbert and his contemporaries. As a clergyman himself, he would be intimately associated with the ideals of pastoral care expected of a priest for his flock. While “high Priest” might suggest to us heavy-handed power, as well as obscure, overwrought religious practices, in practical terms the priest, Rabbi, or minister of a congregation was always ultimately held responsible for the spiritual and often physical well-being of his congregants.36 As Dyck highlights, “Herbert’s priest figure here is not a worldly master but the gardener-parson-poet who attends to the wisdom of each creature in a world in which use and wonder accompany each other” (274). Herbert, we know from poems such as “The Windows” as well as the whole of The Country Parson, took the responsibilities of priesthood very seriously. While he held the position of leader and elucidator of holy mysteries, the priest must answer to God for any “sheep” he lost along the way. The head of a congregation was expected to prioritize the needs of his parishioners. Herbert would know that no aspect of the life of his parish would be too trivial to merit the attention of a truly dedicated minister. The Anglican minister feeds (the Eucharist), educates, and advises his flock. Reading Herbert’s words through the lens of practical pastoral care, rather than as a simple metaphor, changes the way we read “high Priest.” It is a subtle but significant difference: rather than some distant hierophant, we have instead someone who takes on an intimate, parental relationship with his flock. Even the terms “pastoral” and “flock” remind us of the non-human imagery associated with Christian fellowship in a community in which Christ is the Lamb of God. Thus, I argue, the meaning of the words in these lines is considerably blurred. The animals may only mutter assent to the high Priest Man, and he may be the holder of [→ page 174] power and wisdom, but it is done on their behalf, with very real and accountable (to God) consequences if he should fail in his priestly care.

A similar nuancing of this hierarchy can be traced in Herbert’s “Man.”37 Herbert states,

For us the windes do blow,

The earth doth rest, heav’n move, and fountains flow.

Nothing we see, but means our good, (l.25-27)

In these lines the natural world seems reduced to a storehouse of food and tools for human easement. However, Herbert’s stanza describing the world as arranged entirely for us, is more complex than it might at first appear:

Nothing we see, but means our good,

As our delight, or as our treasure:

The whole is, either our cupboard of food,

Or cabinet of pleasure. (ll. 27-30)

The lines in the second part of the stanza clearly suggest a commodification of the world.38 However, I argue, they also suggest the preciousness of that world. The words “delight,” “treasure,” and “cabinet of pleasure” generally suggest something beyond utilitarian servants and tools. They gesture toward cherished possessions that are a source of joy and wonder, a series of beautiful objets d’art that are good in and of themselves. This styling of the world suggests that our modern suspicion of hierarchy may perhaps lead us to miss that Herbert is quite genuine in his wonder and concern for nature, even if he does see humans as rulers over it.

Herbert is understudied as an early modern nature writer by modern scholars. Few attempt to trace how his thinking about the natural world influenced his engagement with nature in daily life, yet, as I have argued, to consider the relationship between theory and practice in Herbert’s life is critical to our understanding of his attitude to the nonhuman world. His writings as Public Orator provide us with a unique window into how this deeply spiritual intellect applied his thinking in the public sphere, in an arena that he knew would have very concrete, [→ page 175] material consequences. The lines from Matthew were never more relevant here: “by their fruits ye shall know them” (Matt. 7:20). Herbert’s fruits, in his letters in defense of the Cam and the university, illustrate a habit of thought that resists easy categorizations of him as unapologetically anthropocentric. His characterization of the Cam as honoured kin, rather than obedient serf, challenges past readings of Herbert as a man who is comfortable with a recklessly commodified and subordinate nature. His insistence, in his letters, of the human duty to the nonhuman Alma Mater, adds further weight to readings of his devotional poetry that find evidence of a more nuanced, inclusive vision of the relationship between humanity and nature in Herbert’s cosmology. Ultimately, as his letters suggest, Herbert’s vision of our place in the world can be most accurately described as one of complex kinship networks, with hierarchal but deeply compassionate and symbiotic relationships.

Works Cited

Ash, Eric. The Draining of the Fens: Projectors, Popular Politics, and State Building in Early Modern England. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins UP, 2022.

Bach, Rebecca. Birds and Other Creatures in Renaissance Literature: Shakespeare, Descartes, and Animal Studies. New York: Routledge, 2018.

Balla, Angela. “Herbert and Gerson Reconsidered: Mystical Music and the Conciliarist Strain of Natural Law in ‘Providence’.” Connotations 33 (2024): 285-327. https://www.connotations.de/article/herbert-and-gerson-reconsidered/.

Borlik, Todd Andrew. “George Herbert. ‘Man’ and ‘Providence.’” Literature and Nature in the English Renaissance: An Ecocritical Anthology. Ed. Todd Borlik. Cambridge: CUP, 2019. 70-75.

Borlik, Todd Andrew. Introduction. Literature and Nature in the English Renaissance: An Ecocritical Anthology. Ed. Todd Borlik. Cambridge: CUP, 2019. 1-23.

Borlik, Todd Andrew. “Renaissance Literature and the Environment.” Oxford Research Encyclopedias: Literature. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190201098.013.1311. 27 May 2024.

Bushnell, Rebecca. The Marvels of the World: An Anthology of Nature Writing Before 1700. Philadelphia: U of Pennsylvania P, 2021.

Calloway, Katie. “A Particular Trust: George Herbert and Epicureanism.” Connotations 32 (2023): 114-44. https://www.connotations.de/article/a-particular-trust-george-herbert-and-epicureanism/.

Calloway, Katie. Literature and Natural Theology in Early Modern England. Cambridge: CUP, 2023.

Camden, William. Britain, or a Chorographicall Description of the Most Flourishing Kingdomes, England, Scotland, and Ireland. Trans. Philemon Holland. London, 1610.

Cox, Jacqueline. “‘The finest place in the University’: George Herbert (1593-1633), Public Orator.” Cambridge University Library Special Collections. 4 Sept. 2020, https://specialcollections-blog.lib.cam.ac.uk/?p=20632. 27 May 2024.

Crover, Sarah. “Gardening, Stewardship and Worn-Out Metaphors. Richard II and Justin Trudeau.” Early Modern Culture 13 (2018): 152-63.

Crover, Sarah. Stage and Street: The Cultural History of the Early Modern Thames. U of British Columbia, 2015.

Dyck, Paul. “The Providential Rose: Herbert’s Full Cosmos and Fellowship of Creatures.” Connotations 33 (2024): 259-84. https://www.connotations.de/article/the-providential-rose-herberts-full-cosmos-and-fellowship-of-creatures/.

Feerick, Jean, and Vin Nardizzi. The Indistinct Human in Renaissance Literature. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012.

Freis, Catherine, and Greg Miller. Introduction. George Herbert’s Latin Prose: Orations and Letters. Ed. and trans. Catherine Freis and Greg Miller. Fairfield, CT: George Herbert Journal Special Studies & Monographs, 2020. v-xxviii.

Freis, Catherine, and Greg Miller. “Notes.” George Herbert’s Latin Prose: Orations and Letters. Ed. and trans. Catharine Freis and Greg Miller. Fairfield, CT: George Herbert Journal Special Studies & Monographs, 2020. 97-138.

McColley, Diane Kelsey. Poetry and Ecology in the Age of Milton and Marvell. Aldershot: Ashgate, 2007.

Fudge, Erica. Perceiving Animals: Humans and Beasts in Early Modern English Culture. New York: St. Martin’s P, 2000.

Glimp, David. “Figuring Belief: Herbert’s Devotional Creatures.” Go Figure: Energies, Forms, and Institutions in the Early Modern World. Ed. Judith H. Anderson and Joan Pong Linton. New York: Fordham UP, 2011. 112-31.

Herbert, George. George Herbert’s Latin Prose: Orations and Letters. Ed. and trans. Catharine Freis and Greg Miller. Fairfield, CT: George Herbert Journal Special Studies & Monographs, 2020.

Herbert, George. “Ad F. Bacon, Cancell.gratiae de fluuio [June 14, 1620] / To Francis Bacon, Chancellor Thanks Concerning the River [June 14, 1620].” George Herbert’s Latin Prose: Orations and Letters. Ed. and trans. Catharine Freis and Greg Miller. Fairfield, CT: George Herbert Journal Special Studies & Monographs, 2020. 46-49.

Herbert, George. “Ad Ful. Grevil. gratiae de Fluuio [June 14, 1620] / To Fulke Greville Thanks Concerning the River [June 14, 1620].” George Herbert’s Latin Prose: Orations and Letters. Ed. and trans. Catharine Freis and Greg Miller. Fairfield, CT: George Herbert Journal Special Studies & Monographs, 2020. 52-53.

Herbert, George. “Ad R. Naunton, Secret. gratiae de Fluuio / To Robert Naunton, Secretary of State Thanks Concerning the River.” George Herbert’s Latin Prose: Orations and Letters. Ed. and trans. Catharine Freis and Greg Miller. Fairfield, CT: George Herbert Journal Special Studies & Monographs, 2020. 50-51.

Herbert, George. “[To King James] gratiae de fluuio contra Redemptores. 1620.14.Ju / [To King James] Thanks Concerning the River in Reply to the Contractors June 14, 1620.” George Herbert’s Latin Prose: Orations and Letters. Ed. and trans. Catharine Freis and Greg Miller. Fairfield, CT: George Herbert Journal Special Studies & Monographs, 2020. 44-45.

Herbert, George. “Man.” The English Poems of George Herbert. Ed. Helen Wilcox. Cambridge: CUP, 2007. 415-27.

Herbert, George. “Providence.” The English Poems of George Herbert. Ed. Helen Wilcox. Cambridge: CUP, 2007. 330-36.

Hiltner, Ken. “Environmental Protest Literature of the Renaissance.” What Else is Pastoral? Renaissance Literature and the Environment. Ithaca, NY: Cornell UP, 2011. 125-55.

Hutchinson, F. E. “Commentary.” The Works of George Herbert. Ed. F. E. Hutchinson. Oxford: Clarendon P, 1941. 475-608.

Johnson, Zane Calhoun. “’all Things Unto our Flesh are Kind’: Corporality and Ecology in the Temple.” George Herbert Journal 42.1 (2018): 128-45.

Johnson, Nicholas. “Anima-tion at Little Gidding.” Early Modern Ecostudies: From the Florentine Codex to Shakespeare. Ed. Thomas Hallock, Ivo Kamps and Karen Raber. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2008. 145-65.

Raber, Karen. Animal Bodies, Renaissance Culture. Philadelphia: U of Pennsylvania P, 2013.

Ralph, Laura E. ‘“Why are we by all creatures waited on?’: Situating John Donne and George Herbert in Early Modern Ecological Discourse.” Early Modern Studies Journal 3 (2010): 1-17. https://earlymodernstudiesjournal.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/ralph3.pdf

Remien, Peter. The Concept of Nature in Early Modern English Literature. Cambridge: CUP, 2019.

Rienstra, Debrah. “’I Wish I were a Tree’: George Herbert and the Metamorphoses of Devotion.” Connotations 32 (2023): 145-64. https://www.connotations.de/article/debra-k-rienstra-i-wish-i-were-a-tree-george-herbert-and-the-metamorphoses-of-devotion/.

Schoenfeldt, Michael. Bodies and Selves in Early Modern England: Physiology and Inwardness in Spenser, Shakespeare, Herbert, and Milton. Cambridge: CUP, 2000.

Spenser, Edmund. The Works of Spenser: The Faerie Qveene. A Variorum Edition. Vol 4. Ed. Ray Hefner. London: OUP,

Ring out, wild bells, to the wild sky,

Ring out, wild bells, to the wild sky,