Lost and Found: Textual and Intertextual Retrieval in Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s Exhumation Letters and the “Willowwood” Sonnets

Carl Plasa

Published in Connotations Vol. 33 (2024)

Abstract

This article is divided into two sections, the first of which is concerned with Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s letters, written between 17 December 1868 and 26 October 1869, in which he considers the exhumation of the manuscript of his poems that he buried with his wife, Elizabeth Eleanor Siddal, following her probable suicide in February 1862. While this macabre act of textual retrieval, carried out in Highgate Cemetery on 5 October 1869, is the most infamous incident in Rossetti’s biography and mid-Victorian literary history in general, the argument here is that its epistolary construction has not received due critical examination, just as Rossetti’s voluminous correspondence as a whole remains the least studied element of his intermedial œuvre.

In its second section, the article turns the critical focus from Rossetti’s letters to his “Willowwood” sonnets, as first published in the Fortnightly Review on 1 March 1869, contending that this quartet of poems not only precedes the disinterment in a chronological sense but also contains several covert prefigurations of the episode, which it falls to the reader to uncrypt. Yet if the sonnets obliquely foreshadow the exhumation—and indeed are central to the very book (Poems [1870]) whose publication motivates the undertaking in the first place—they also have an ultimately more significant retrospective dimension, in the shape of their intertextual dialogue with John Keats’s “Isabella; or The Pot of Basil” (1820). As the article demonstrates, Rossetti’s turn to Keats’s text is neither random nor surprising since “Isabella” is itself marked by lurid scenes of burial and disinterment, loss and reclamation which would surely have resonated with the troubled artist-poet. What is surprising, however, is that “Isabella”’s presence in “Willowwood” has to date gone altogether unnoticed, despite the extensive critical debate which, in sharp contrast to Rossetti’s correspondence, the sonnets have provoked.

Introduction

Although better-known as an artist, Dante Gabriel Rossetti was also a poet of considerable stature, and at the end of 1861 his prospects in this latter regard seemed bright. He had just published The Early Italian Poets from Ciullo D’Alcamo to Dante Alighieri, a book of translations of material “hardly kept alive through centuries of neglect” (D. G. Rossetti, “Preface” viii) and was on the cusp of publishing Dante at Verona and Other Poems, a collection of his own original verse, due to appear in the following year. Yet this dynamic publishing programme was dramatically upset by the likely suicide from a laudanum overdose of his wife, Elizabeth Eleanor Siddal, on 11 February 1862, less than two years after their marriage on 23 May 1860. Stricken with grief and guilt, Rossetti committed his unpublished manuscript to Siddal’s coffin at the time of her funeral six days later, adding it to the gift of the Bible that had been lodged there too. According to report, he followed this grand gesture of poetic self-renunciation with an equally grand statement, telling Ford Madox Brown: “‘I have often been writing at those poems when Lizzie was ill and suffering, and I might have been attending to her, and now they shall go’” (qtd. in W. M. Rossetti, Dante Gabriel Rossetti 1.225).

Rossetti’s inhumation of his lost book, “bound in rough grey calf” with “red edges to the leaves” (D. G. Rossetti, Correspondence 281), was not, however, the last chapter in that book’s story but only its first. Seven and a half years later he took the decision, encouraged by Charles Augustus Howell—friend, agent and accomplice—to exhume his poems, an operation duly performed in Highgate Cemetery on the night of 5 October 1869 at a cost of two guineas, paid to a Blackfriars funeral company.1 While Rossetti himself was not present at this notorious event (it was supervised by Howell instead), he writes about it in his [→ 192] letters, in a style ranging from the indirect to the taciturn and the detailed but business-like to the self-exonerating, and it is this correspondence, produced between mid-December 1868 and late October 1869, that provides the focus for this article’s first section. In a departure from the critical norm, the approach to this epistolary corpus adopted here favours it with the same kind of close textual analysis usually reserved for Rossetti’s poetry and, in a secondary critical swerve, also reads Rossetti’s exhumation scheme alongside his concurrent desire for the return of another precious thing, Siddal’s Clerk Saunders (1857), as announced in a letter of 19 April 1869 to Charles Eliot Norton, the drawing’s American owner at the time. Why should Rossetti’s wish to reclaim Clerk Saunders surface at this particular juncture? In what ways does Siddal’s haunting watercolour tie in with the concerns of the evolving disinterment project?

In its second section, the article shifts the spotlight onto Rossetti’s “Willowwood” sonnets, completed on 18 December 1868 (see Lewis 119), one day after Rossetti makes his initial epistolary allusion to the idea of the exhumation, coded, in a reply to Howell, as “the poem question” (Correspondence 131). These four interlinked texts (often conveniently grouped under the rubric of “Willowwood”) first appeared in the Fortnightly Review on 1 March 1869 at and as the beginning of a larger sequence titled “Of Life, Love, and Death: Sixteen Sonnets.” Subsequently they became the literal and figurative centrepiece of The House of Life, a greatly augmented version of the original series included in Rossetti’s Poems (1870), the volume in whose service the exhumation had been carried out. This version of the sequence was in turn more than doubled in size (rising from fifty to 101 sonnets) when published in definitive form in Ballads and Sonnets in 1881, one year before Rossetti’s demise.

Unlike the exhumation letters, which turn upon the fetishistic desire to retrieve a lost book and concomitantly bring about Rossetti’s rebirth from the poetic silence in which he had entombed himself, “Willowwood” is animated, in the first instance, by a more radical yearning, as [→ 193] its speaker hallucinates reunion with his late wife, before finally conceding the impossibility of ever actuating such a goal.2 Yet even as these poems are thus thematically concerned with a different type of loss to that navigated in the letters, they nonetheless contain a number of anticipatory traces of the exhumation incident which can be uncovered by close attention to the specific features of Rossetti’s language, from words and images (some of which are perhaps puzzling or unexpected) to the phonetic patterning of his verse.3

While these curiously prospective traces are an important facet of “Willowwood,” they are ultimately secondary to the sonnets’ intertextual dialogue with John Keats’s “Isabella; or, The Pot of Basil” (1820). It is perhaps not surprising that Rossetti should gravitate towards this particular text at the time since it shares his own preoccupations with burial and exhumation; yet what is surprising is that “Isabella”’s presence in “Willowwood” has to date gone altogether unnoticed, despite the extensive critical debate which, in sharp contrast to Rossetti’s letters, the poems have generated. “Isabella” might thus be construed as a lost or buried text that invites its own kind of retrieval, a secret counterpart or companion, as it were, to the book hidden underground with Siddal in Highgate.

1. The Exhumation Letters: “Bogies” and Revenants, an Owl and a Worm

Rossetti’s eyes desire some feverish thing, but the mouth and chin hesitate in pursuit. All Rossetti is in that story of his MS. buried in his wife’s coffin. He could do it, he could repent of it; but he should have gone and taken it back himself: he sent his friends.

Eleanore Duse, qtd. in Symons 51 (italics in original)

During the year or so leading up to the retrieval of his manuscript, Rossetti’s letters repeatedly refer to a “spell of ill health” (Correspondence 153), mentioning, in particular, “a break-down in eyesight.” This causes him to experience “a tendency to waving and swimming in all that [he looks] at” (Correspondence 106) as well as “[w]hirling [and] flickering” (Correspondence 95)—symptoms that implicitly threaten the son with [→194] the blindness which the father, Gabriele Rossetti, himself constantly feared.4 These ocular disorders prove to be psychosomatic and, in the words of Henry Treffry Dunn, Rossetti’s studio assistant, are part of what makes him “at times [...] a veritable Malade Imaginaire” (qtd. in D. G. Rossetti, Correspondence 3; italics in original), even as they have far-reaching consequences both negative and positive. They oblige Rossetti to limit his activities as painter, on the one hand, and turn (or return) to the art of poetry as his creative outlet, on the other.

The first public sign of this reorganisation of imaginative energies takes the form of the sonnets in the Fortnightly, which, as Rossetti wrote to William Allingham on 23 December 1868, were a combination of “ravelled rags of verse” (Correspondence 136) stretching back to the early 1850s and new work written up to within a few days of the letter’s festive dating and which of course includes “Willowwood.” When he proudly encloses these compositions in a letter written to his mother on the day of their publication, however, Rossetti introduces them in a language far less matter-of-fact than that used for Allingham—a peculiar mix of the skittish and the ghoulish:

I send you my sonnets, which are such a lively band of bogies that they may join with the skeletons of Christina’s various closets, & entertain you by a ballet. Their shanks are rather ghastly, it is true, but they will keep their shrouds down tolerably close, and creak enough themselves to render a piano unnecessary. As their own vacated graves serve them to dance on, there is no danger of their disturbing the lodgers beneath, and, if any one overhead objects, you may say that it amuses them perhaps and will be soon over, and that as their hats were probably not buried with them these will not be sent round at the close of the performance. (Correspondence 156-57)

As Rossetti’s editor, William E. Fredeman, speculates, “[p]erhaps the overwrought danse macabre imagery here reveals DGR’s dread of his mother finding out about the projected exhumation” (D. G. Rossetti, Correspondence 157n1; italics in original), a fear compounded by the fact that Frances Mary Lavinia Rossetti was the owner of the family grave (which Siddal shared with Rossetti’s purblind father, interred there in 1854), and would need to grant her consent before it could be unsealed. Yet if the “imagery” of this passage “reveals” a “dread” of maternal [→ 195] discovery, it might be wondered why Rossetti should feel moved to deploy it. Perhaps—to extend Fredeman’s speculations—it is that, far from wanting to keep his nascent plans a secret, he wishes to confess them, or, to be more precise, to do both things at once? Such ambivalence expresses itself in the chain of gothic tropes which dominates this passage and which functions as a form of screen, in the double sense of the word as something which both hides and displays. For Rossetti’s mother, the metaphors of “bogies,” “skeletons,” “shrouds” and “graves” conspire to form an innocent if disquieting pantomime, applying, as they do, to the poems her son had just published. For the knowing reader, conversely, these sinister figures are burdened with associations pointing unequivocally towards Plot No. 5779 in Highgate Cemetery and the “disturbing” of the “lodgers beneath”—or one of them, at least—that will take place some seven months later. As Angela Leighton puts it, there is “[s]omething in the show of the writing [that] signals the very thing [Rossetti] would hide” (3).

This passage is a “rare” moment of “verbal flamboyance” (Leighton 3) in Rossetti’s epistolary archive and has two further aspects to be considered here. The first entails a certain parallel between Rossetti’s “sonnets,” defined as a “lively band of bogies,” and the letter in which they appear, which, as William Michael Rossetti notes, is itself written in “so deadly-lively a style” (Dante Gabriel Rossetti, 2.200). This highly charged maternal missive is, in other words, just as entertaining as the “ballet” Rossetti imagines his poems performing in concert with his sister’s; and the “show” is rendered all the more appealing, in turn, because it is not being put on for financial gain. The “hats” belonging to the troupe of creaking sonnet-bogies “were probably not buried with them,” Rossetti jests, and so are unlikely to be circulated for money when the dance is done.

The second and more complex of these additional aspects, which no critic has so far remarked upon, is the strange pas de deux which the passage enters into with an anecdote recounted in William Bell Scott’s Autobiographical Notes (1892). Here Scott, who was one of the few whom [→ 196] Rossetti was to tell about the “projected exhumation,” recalls an exchange with his friend when he was staying with him at Penkill Castle in Scotland in the autumn of 1868:

It was now midsummer, and [Alice Boyd], finding D. G. R. in a depression of mind from the idea that his eyes were failing, prevailed upon him to accompany me to Ayrshire for an autumn vacation. He did so; we were a party of four—Miss Boyd’s cousin, Miss Losh of Ravenside, being a visitor at that time. This old lady—she was about seventy years of age—had somehow or other taken a jealous dislike to me, thinking I had too much influence over her younger cousin, who entertained me so much and who lived with us in London in the winter. She had therefore looked forward to Rossetti’s appearance, fully intending to play him off against me, which accordingly she did in the most fantastic way, without in the least knowing anything of the fearful skeletons in his closet, that were every night, when the ladies had gone, brought out for his relief and my recreation. These skeletons, which were also made to dance along the mountain highroad during our long walks, would have surprised the old lady not a little. They shall not be interviewed here, and without them we got on pretty well, although his talk continually turned upon his chance of blindness and the question, why then should he live? “Live for your poetry,” said I. Strangely enough, this seemed never to have occurred to him as a possible interest or resource. Live for your poetry was echoed by the ladies. (108-09)

Scott’s language resonates strongly with the gruesome yet exuberant flight of imagination in Rossetti’s letter, making it clear that the unruly “skeletons” Rossetti bundles into Christina’s “closet” more truly belong in his, even as she is the author of poetic “bogies” of her own, the most celebrated of which is “Goblin Market” (1862). It is not that Scott echoes Rossetti here, since Rossetti’s letter did not appear in print until 1895, but rather that Rossetti echoes Scott; or rather the conversation which took place between them during his troubled autumnal retreat at Penkill.5

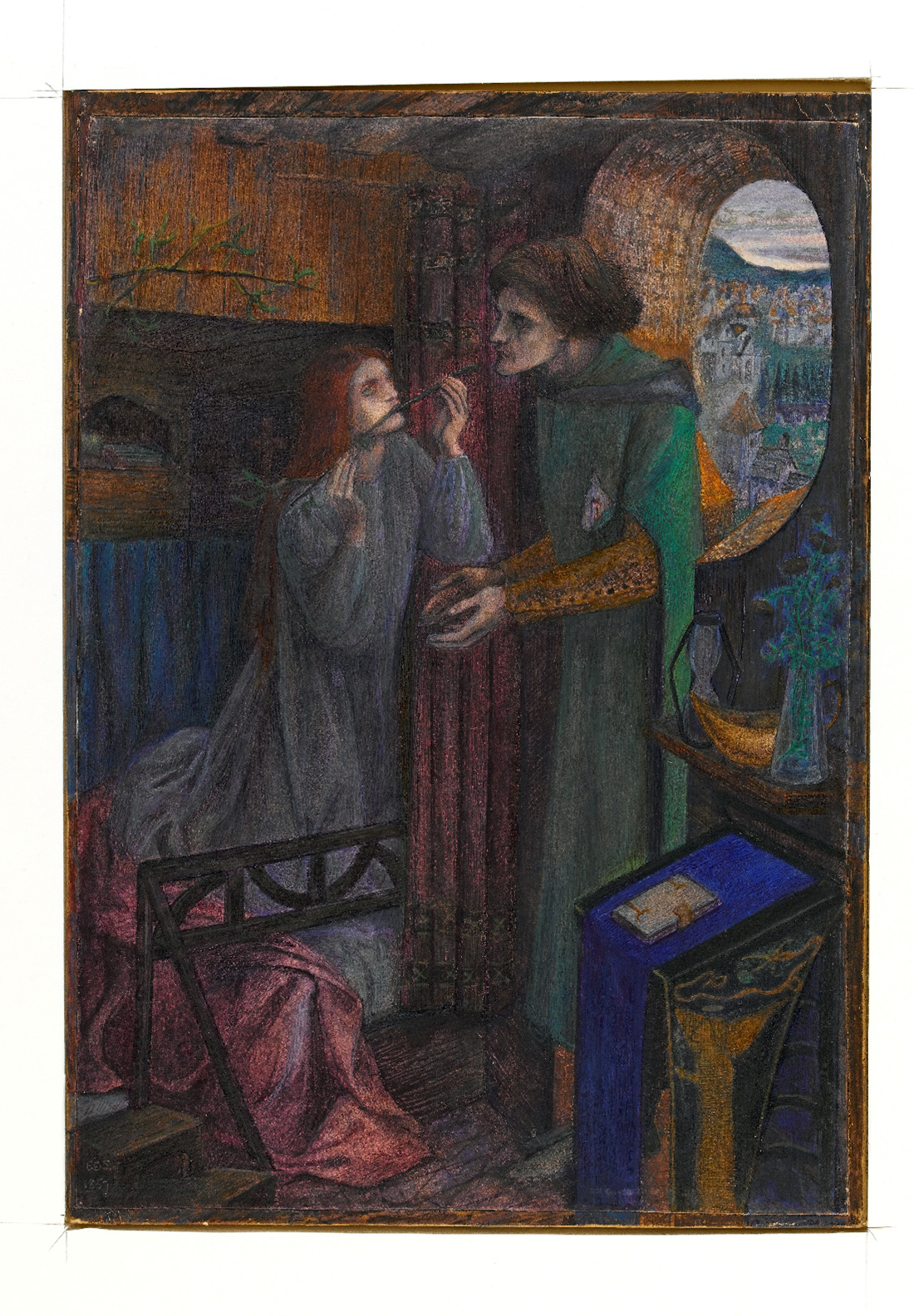

At the same time as engaging in the exhumation scheme, which the letter to his mother both masks and “signals,” Rossetti embarks upon the pursuit of Siddal’s Clerk Saunders (Fig. 1). Here is how he frames that pursuit in the letter to Norton mentioned at the start of this article:

I have long wished to make a proposal to you. It would be a great satisfaction to me to possess the drawing you have by my late wife of “Clerk Saunders” [→ 197] to add to those of hers which are now mine, and which every year teaches me to value more & more as works of genius, even apart from their personal interest to me. None would ever have been parted with, of course, had we not then hoped that these little things were but preludes to much greater ones,—a hope which was never to be realized. (Correspondence 175)

The “drawing” to which Rossetti refers in this passage was one of seven works that Siddal first displayed as part of the Pre-Raphaelite Exhibition held at Russell Place in 1857 and that Norton purchased after viewing it in “the British Art Show that toured the United States later that year” (Dunstan 25). It is not an original creation, but inspired, like so much Pre-Raphaelite art, by a medieval source, in this instance the eerie and eponymous folk ballad, “Clerk Saunders.” As Nat Reeve observes, Siddal would have found a version of this ballad in her 1807 edition of Sir Walter Scott’s Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border (1802-03) (see Reeve 77).

Rossetti’s respective quests for Clerk Saunders and his far-flung book are not just linked in terms of their chronological overlap, however, but intimately imbricated in other ways, even as they are in some respects at odds. The first of their connections is that both Siddal’s picture and Rossetti’s manuscript constitute material symbols of creative potential abruptly truncated and laid waste, albeit temporarily in his case. The second is that the picture Rossetti would like returned to him is itself based on a tale of revenancy, in which Saunders comes back from his grave to visit his lover, Margaret, after he has been murdered by one of her seven brothers for having sex with her outside wedlock.

As much as it is about a visitation from the grave, “Clerk Saunders” is a story that ends, all the same, with a “troth-breaking ritual” (Reeve 86n35) and a leavetaking, and it is this decisive rupture between lovers on which Siddal chooses to focus. As Reeve glosses the picture:

May Margaret kisses a willow wand for her lover Clerk Saunders. Saunders is a revenant, stabbed the day before by Margaret’s brothers, back from his grave to set the couple free from their binding lovers’ vows. The pair enact [sic] a ritual separation, where Margaret’s gift of the willow wand releases Saunders from his spectral state. (73) [→ 198]

Clerk Saunders thus heralds a return to the grave that is antithetical to the path Rossetti has staked out for his lost manuscript.

Nonetheless, Clerk Saunders includes other elements that once again link it to the exhumation, since, like Siddal’s coffin, the picture contains two texts, each of which is a Book of Hours, with neither featuring in the original ballad. The first lies on a lectern towards the drawing’s bottom-right corner and appears to be in immaculate condition, its clasp unopened, while the second is less obtrusively located in the “alcove over Margaret’s bed” (Reeve 78). As Reeve elaborates, this item:

is a similar size to the Book of Hours on the lectern, but its covers are a drab green and faded at the edges, and a rough brushstroke technique has been used to depict loose pages poking out of the top. The second book’s devotional accoutrement—a small wooden crucifix—is not as grand as the decorated lectern. Yet, unlike the lectern book, the painting [sic] emphasizes that the second book is battered with use. (78)

In terms of the story that Clerk Saunders reimagines, the ghostly doubling of the first book by the second can be read as symbolising Margaret’s passage from virgin to fallen woman. Yet in the context of the exhumation, it assumes another significance and figures another fall, as the calf-skin volume Rossetti initially insisted his “late wife” take with her as she heads on into the afterlife eventually comes back to him in a “bad state” and is a “sad wreck” (D. G. Rossetti, Correspondence 312, 311).

As can be inferred from a letter to Jane Morris of 14 August 1869, Rossetti’s desire for the return of Clerk Saunders has been met by that date, prompting him to describe the picture as a “water-colour by poor Lizzy” that “looks very fine though certainly quite quaint enough” (Correspondence 232), an appraisal noticeably more muted than that given in the letter to Norton, where the drawing is catalogued among Siddal’s “works of genius.” Be that as it may, two days after this letter and with the image safely back in his hands, Rossetti redirects his attentions to his more ambitious salvage operation. He resumes the exchange with Howell on the matter that the two had begun some eight [→ 199] months earlier and haltingly informs his interlocutor that he now finally “feel[s] disposed, if practicable [...] to go in for the recovery of [his] poems if possible” (Correspondence 235).

Nicknamed “Owl” among Pre-Raphaelite circles, Howell was Rossetti’s agent not only in the mid-Victorian art-world, selling a large number of his paintings and drawings (see Cline vii), but also in the underworld realm of the exhumation plot, offering him various forms of “friendly aid” (D. G. Rossetti, Correspondence 235). These included asking the Home Secretary, Henry Austin Bruce, to waive the permission for the opening of Siddal’s grave that would ordinarily have been required from its proprietress and presiding over the exhumation itself, in the company of several others. These were the lawyer, Henry Virtue Tebbs, recruited to assure the “Cemetery authorities” that the “removal” of the “papers” from Siddal’s coffin was not being perpetrated in the name of a “fraud” (D. G. Rossetti, Correspondence 303); a doctor, Llewellyn Williams, who served as the exhumation’s “medical witness”; and “two [...] workmen” (Matthews 20) to do the digging.

But as well as operating as his client’s surrogate in the “trying task” (D. G. Rossetti, Correspondence 303) of the disinterment, Howell was widely reputed during his lifetime to have a “fatal gift for romancing, or inability to discriminate between fact and fiction” (Angeli xi; italics in original) and is commonly regarded as the likely source of the well-known cover story that arose after Rossetti’s grave-goods had been reclaimed. That story was designed to palliate both the enormity of the desecration that had occurred and the realities of post-mortem decay (as charted more fully below) and involved two related assertions. Firstly, that when Siddal’s tomb was pried open, her “body” was “still beautiful” (Matthews 25); and, secondly, that “her red hair had grown in death until it filled the coffin,” its “glowing colour” (Marsh, Legend 28) matching the decorative “red edges” of the “leaves” of the book her husband had entrusted to her care.

Rossetti embraces these fabrications uncritically, overtly echoing the second, in particular, in the final line of “Life-in-Love,” Sonnet XVI from the 1870 iteration of The House of Life, where the poem’s speaker [→ 200] finds himself dazzled by his beloved’s “golden hair” as it “[l]ies [...] undimmed in death” (l. 14). He also echoes them, albeit more laconically, in his correspondence, as, for instance, in a confessional post-exhumation letter to William Michael of 13 October 1869. After advising his brother, about halfway through his account, that “the thing is done,” Rossetti writes:

All in the coffin was found quite perfect, but the book, though not in any way destroyed, is soaked through & through and had to be still further saturated with disinfectants. It is now in the hands of the medical man who was associated with Howell in the disinterment, and who is carefully drying it leaf by leaf. There seems reason to fear that some minor portion is obliterated, but I must hope this may not prove to be the most important part. I shall not I believe be able to see it for at least a week yet. (Correspondence 302-03)

Here it is not only that Rossetti elides any reference to the fiery miracle of Siddal’s hair, but also that he seems reluctant to dwell upon her post-mortem appearance per se, gliding past it in one tight-lipped statement—“[a]ll in the coffin was found quite perfect”—as if anxious not to allow the recipient of such a remarkable report the chance to dwell upon or challenge it. Leaving aside its questionable provenance, the statement is hardly persuasive, especially as it is immediately contradicted when Rossetti switches the focus to the “book” that is his main concern and laments its dilapidated condition. Even considered in isolation, the statement is “actually [...] ambiguous” (Lutz, Pleasure 22), since “quite” has two senses which are at odds with one another: the word can mean “entirely” (OED; sense I.), on the one hand, and “relatively” or “reasonably” (OED; sense III.) on the other.

The meretricious and self-serving stories concocted by Howell and replicated by Rossetti are not difficult to dismantle, especially when juxtaposed with sources the artist-poet would know well. One such source is “Clerk Saunders” and specifically the dialogue towards the ballad’s end, where Margaret implores her revenant-lover to accommodate her in the grave into which he is about to vanish:

‘Is there ony room at your head, Saunders?

Is there ony room at your feet?

Or ony room at your side, Saunders,

Where fain, fain, I wad sleep?’ [→ 201]

‘There’s nae room at my head, Marg’ret,

There’s nae room at my feet;

My bed it is full lowly now:

Among the hungry worms I sleep.

‘Cauld mould is my covering now,

But and my winding-sheet;

The dew it falls nae sooner down,

Than my resting-place is weet.’ (ll. 109-20)

Or there is Christina Rossetti’s “Death” (1848), whose chilling opening offers a yet more pertinent evocation of the posthumous outrages Siddal’s corpse might have sustained during its slumbers beneath the earth:

“The grave-worm revels now”

Upon the pure white brow,

And on the eyes so dead and dim,

And on each putrifying limb,

And on the neck ’neath the long hair;

Now from the rosy lips

He damp corruption sips,

Banquetting everywhere.

Creeping up and down through the silken tresses

That once were smoothed by her husband’s caresses,

In her mouth, and on her breast. (ll. 1-11)

From these terrifying perspectives, it is clear that Rossetti’s fraternal disclosure of the fact of the exhumation produces its own secrets, as he disavows the processes of physiological decomposition the two excerpts just cited so graphically dramatise, purging them from his prose with the same diligence as the “medical man” disinfects the cherished “book” of the contagions in which it is “soaked.”

Yet even as Rossetti refuses explicitly to acknowledge such processes, they are still active beneath the surface of his language, concealed and revealed at once. This is perhaps most strikingly evident when he writes to Brown the day after penning the confessional letter to William Michael: [→ 202]

I went today to see those M.S.S. at the Doctor’s, and I shall be able to have them in a few days. They are in a disappointing state,—the things I have already seem mostly perfect, and there is a great hole right through all the leaves of ‘Jenny’ which was the thing I most wanted. A good deal is lost but I have no doubt the things as they are will enable me with a little re-writing & a good memory & the rough copies I have to re-establish the whole in a perfect state. (Correspondence 304)

In this mixed review of Rossetti’s “M.S.S.”—they are “disappointing” but have the potential to return to a “perfect state”—the worm that bores the “great hole through all the leaves of ‘Jenny’” does double duty: its ruinations metaphorise those to which Siddal’s dead body would have been exposed and which are gruesomely glimpsed in “Clerk Saunders” and “Death” alike.

This reading is strengthened when it is recalled that “Jenny” is itself a poem in which the boundaries between books and bodies are often porous. For example, when the “young and thoughtful man of the world” (D. G. Rossetti, “Stealthy” 338) who speaks this dramatic monologue vacates his book-lined study to spend the night with the poem’s drowsy-headed prostitute-heroine, it is only to transform her, by ironic implication, into an electrifying volume of pornography spread out for his voyeuristic delight:

Why, Jenny, as I watch you there,—

For all your wealth of loosened hair,

Your silk ungirdled and unlac’d

And warm sweets open to the waist,

All golden in the lamplight’s gleam,—

You know not what a book you seem,

Half-read by lightning in a dream! (ll. 46-52)

Similarly, when he considers sharing his unspoken thoughts by verbalising them for his exhausted and perhaps indifferent companion, he again turns Jenny into a bookish figure:

What if to her all this were said?

Why, as a volume seldom read

Being opened halfway shuts again,

So might the pages of her brain

Be parted at such words, and thence

Close back upon the dusty sense. (ll. 157-62) [→ 203]

But as Rossetti’s intrepid if invisible book-worm penetrates “Jenny”’s “leaves,” its actions not only remind the reader of the similarly unseen fate that befalls Siddal’s remains. They also assume an erotic, not to say necrophiliac dimension, as the violations suffered by the material “thing” that is Rossetti’s poem mirror those suffered by that poem’s heroine as the inevitable consequence of her profession. At the same time, those actions recall the “revels” enjoyed by the “grave-worm” in Christina Rossetti’s “Death,” a creature which “[b]anquet[s]” on, but also down, the dead wife’s blazoned body, travelling with alliterative purpose from “brow” to “breast”—and entering her “mouth” en route. Such a trajectory tacitly leads back, in a further chronological and corporeal descent, to Andrew Marvell’s “To His Coy Mistress” (1681) and the moment when yet other “worms,” rather than Marvell’s coercive first-person suitor, will “try” the mistress’s “long preserved virginity” (ll. 27, 28), reducing her “quaint honour” to “dust” (l. 29).

As Rossetti’s letter to Brown indicates, his chagrin at the mess of his “M.S.S.” is aggravated by the fact that the section he is keenest to secure is the one most severely vitiated: “there is a great hole right through all the leaves of ‘Jenny’ which was the thing I most wanted,” to recall his formulation. Yet while the obvious meaning of this comment makes it an expression of complaint and dismay, the text is open to a supplementary reading which gives it an opposite sense, with the phrase “which was the thing I most wanted” applicable not to “Jenny” itself but to the “great hole” that has been tunnelled “right through” it. Rossetti’s exhumation correspondence officially defines his overriding priority as the pursuit and reclamation of the talismanic calf-bound book, but what is suggested here, by contrast, is an unexpected collusion with and celebration of the lowly agent of that book’s defacement. Such a reading is a long way from overturning the dominant sense of the comment under consideration. After all, when it reappears in Rossetti’s next letter to his brother of 15 October 1869, it is reworded in such a way as fully to remove its ambiguity, while also making explicit the species of creature responsible for such thoroughgoing literary vandalism: “[t]he poem of ‘Jenny’ which is the one I most wanted, has got a great worm- [→ 204] hole right through every page of it” (Correspondence 304). Even so, the textual slippage is worth recording, not least because it is consistent with and symptomatic of the self-destructive remorse for Siddal’s death with which Rossetti initially relinquishes his work: “‘I have often been writing at those poems when Lizzie was ill and suffering, and I might have been attending to her, and now they shall go.’”

This conflict between the desire, on the one hand, to restore “Jenny” (and the book of which it is so vital a part) and, on the other, to have them both violated is spelt out in Rossetti’s language. As the letter closes, he assures Brown (and himself) that “with a little re-writing & a good memory & the rough copies” which he has, he will be able “to re-establish the whole in a perfect state.” But the terms in which he anticipates this utopian moment undermine and reverse it, as “whole” is not only a homophone of but also infiltrated by “hole,” the very word that signifies the book’s currently disfigured and sorry condition. As if in secret recognition of the one who assisted Rossetti in recovering his manuscript, “whole” at the same time offers a near-anagram of Howell’s owlish and ill-omened surname.

The contradictions that worm their way into Rossetti’s comment to Brown about the damage done to “Jenny” recur elsewhere in the course of his post-exhumation confessions. They can be seen, for instance, in the last of the letters to be considered here, sent to Algernon Charles Swinburne on 26 October 1869:

I want to tell you something lest you should hear it first from any one else. It is that I have recovered my old book of poems. Friends had long hinted such a possibility to me, but it was only just lately I made up my mind to it. I hope you will think none the worse of my feeling for the memory of one [Siddal] for whom I know you had a true regard. The truth is, that no one so much as herself would have approved of my doing this. Art was the only thing for which she felt very seriously. Had it been possible to her, I should have found the book on my pillow the night she was buried; and could she have opened the grave, no other hand would have been needed. (Correspondence 312)

Here Rossetti delivers a masterclass in speaking for the other. First he calls on the victim of the exhumation to legitimate it and then asserts that she would surely have sent his “old book of poems” back to him [→ 205] almost immediately, out of a high-minded concern that “Art” not be deprived of a “treasure” (D. G. Rossetti, Correspondence 313)—to use Swinburne’s term, in response to this letter two days later. But does Rossetti’s cosy bedtime fantasy behave quite as he would like it to do? Is Siddal’s imagined gesture driven by the motivations he ascribes to it? Or is her swift return of the coveted book rather the sign of its disdainful rejection?

As this passage makes clear, Rossetti’s ultimate concern is not for reunion with Siddal but with his “old book of poems”: Siddal is invoked here merely as the means to that end, a kind of surrogate for Howell, who is himself a surrogate for Rossetti. “Willowwood,” conversely, is dominated by the possibility of just such a reunion between the poems’ widower-speaker and his late wife, the mourner and the mourned, even as such a notion is eventually renounced. As becomes evident, however, the story told by these four sonnets is far too complex to be delimited by its explicit theme, articulated as it is in a language which both looks forward to “the projected exhumation” (to cite Fredeman again) and back to Keats’s “Isabella.”

2. The “Willowwood” Sonnets: Prospect and Retrospect

Eyes that last I saw in tears

Through division

Here in death’s dream kingdom.

Eliot, “Eyes That Last I Saw in Tears” (ll. 1-3)

In an early twentieth-century reading of “Willowwood,” Paull Franklin Baum makes the striking (if strikingly undeveloped) assertion that the place that gives this quartet of sonnets its name “is a grave [...] sacred to those who have loved and lost and cannot forget” (141). More precisely, though, it is less Willowwood itself that fits that designation than the well introduced in sonnet one. This provides the mystical focus for the “Willowwood” sequence overall and is, by extension, at the heart of The House of Life in both its iterations: [→ 206]

I sat with Love upon a woodside well,

Leaning across the water, I and he;

Nor ever did he speak nor looked at me,

But touched his lute wherein was audible

The certain secret thing he had to tell:

Only our mirrored eyes met silently

In the low wave; and that sound came to be

The passionate voice I knew; and my tears fell.

And at their fall, his eyes beneath grew hers;

And with his foot and with his wing-feathers

He swept the spring that watered my heart’s drouth;

Then the dark ripples spread to waving hair,

And as I stooped, her own lips rising there

Bubbled with brimming kisses at my mouth. (“Willowwood I,” ll. 1-14)6

As observed above, one of the stories emerging from the exhumation of Rossetti’s lost book was that, in contrast to the book itself, when Siddal’s coffin was opened, she was “said to have appeared radiantly beautiful, a figure of fine pallor among an abundance of red golden hair” (Bronfen 177), and these conditions seem loosely prefigured here by the phantom woman who picks her way back piecemeal from the dead. As if to underline such prescient parallels, the surname of the one reputed to have propagated the story is half-submerged in the “well” of the sonnet’s opening line, just as his avian soubriquet equips him with “wing-feathers” to match those Love uses to whisk “dark ripples” into “waving hair.”

As Rossetti reads it, this sonnet “describes a dream or trance of divided love momentarily re-united by the longing fancy” (“Stealthy” 337), bearing witness to a “resurrection” celebrated by a kiss “that resembles a champagne toast” (Bullen 431, 435). This intoxicating moment of miraculous return is immediately followed, at the start of “Willowwood II,” by Love’s commencement of its “song,” even as, far from being jubilant or forward-looking, the song is sorrowful and “meshed with half-remembrance” (ll. 1, 2). It draws the speaker into doleful recollections of the past and, specifically, the past selves belonging both to him and his beloved as they materialise uncannily around him, in the eponymous and claustrophobic setting of Willowwood, as “mournful [→ 207] forms” (l. 7) with “one” stationed “by every tree” (l. 6). But while these ubiquitous and funereal figures constitute the traces of seemingly interchangeable identities gone by (“for each was I or she,” l. 7), they are also bound up with the affliction of the present. What they summon back to mind and symbolise, as they stand “aloof” from one another, is an intermittent silence and separation between the spouses when both of them were alive, represented as “those [...] days that had no tongue” (ll. 6, 8), that has been rendered far more difficult to circumvent now that one partner in the marriage is dead.

At the same time, however, to read the phrase in this way is not to exhaust its meaning, since it can also be taken as a gloss on the Rossettian song that is “Willowwood” itself and the manner in which the sequence is “meshed” with “Isabella,” a text based on the fifth story from the fourth day of Giovanni Boccaccio’s Decameron (c. 1349-1351). Al-though critics so far have not examined “Isabella” as an intertext for “Willowwood,” a brief reprise of Keats’s poem suggests there are good reasons why Rossetti might have been attracted to it while composing these sonnets, during a period which feeds into the time in which the disinterment plot was hatched, developed, executed and selectively disclosed. The first two thirds of “Isabella” tell a gothic story of illicit love between its two principals, the eponymous heroine and Lorenzo; Lorenzo’s murder by his lover’s two avaricious merchant-brothers and their burial of his body in a “sylvan grave” (Lutz, Relics 39); and the return of the “murder’d man” (“Isabella” l. 209) to Isabella as a revenant in a dream. This part of the narrative has clear affinities with “Clerk Saunders,” but “Isabella” diverges from the ballad in its last third, as the heroine follows the instructions of Lorenzo’s “Spirit” to visit his “tomb” (ll. 321, 304), before going on to exceed those instructions in startling fashion. She not only exhumes Lorenzo’s body with the help of her “aged Dame” but also decapitates it, reburying the severed head in a “garden-pot” covered with “[s]weet Basil, which her tears kept ever wet” (ll. 346, 414, 416). The head, “vile with green and livid spot” (l. 475), is finally re-exhumed by the watchful and guilt-ridden brothers, who take it with them into self-imposed exile.7

[→ 208] Yet while Keats’s poem would have a broad thematic resonance for Rossetti, there is an important sense in which “Isabella” and “Willowwood” do not marry up with but are diametrically opposed to one another. For J. B. Bullen, “Willowwood” offers an imaginative staging of “Rossetti’s need to come to terms with the death of his wife” (432), fictionalising the painful psychic labour Freud describes in “Mourning and Melancholia” (1917), whereby the love-object is gradually decathected in a process whose completion allows “the ego” to become “free and uninhibited again” (Freud 245) and hence at liberty to form new emotional attachments. In “Isabella,” however, no such felicitous psychic destiny presents itself, as the heroine is unable to let go of Lorenzo’s memory—or perhaps it will not let go of her?—and, finally overwhelmed by her sense of loss, descends into madness.

“Isabella”’s subterranean role in “Willowwood” can be initially detected by looping back to the opening sonnet. Here Love’s “eyes” are not just ”mirrored” in the waters of the well-grave or grave-well into which they look but also catch a glancing reflection from the “eye” belonging to the corresponding amatory personification who appears in the first stanza of Keats’s text and regards Lorenzo as a “young palmer”

(l. 2) or pilgrim. Similarly, the “lute” whose “sound” comes to be imagined by Rossetti’s speaker as his wife’s “passionate voice”—an instance of what Freud calls “hallucinatory wishful psychosis” (244)—harmonises with Isabella’s own medieval “lute-string” which, in the second stanza of Keats’s poem, yields “an echo” of Lorenzo’s “name” (l. 15).

Along with these details from “Isabella”’s opening two stanzas, “Willowwood I” incorporates as well as revises further and more significant elements from three much later moments in Keats’s poem. The first of these moments involves the visit the slaughtered Lorenzo pays his dreaming lover in stanza 35, at a point in the narrative when Isabella is as yet in “ignorance” (l. 265) of her brothers’ crime:

It was a vision.—In the drowsy gloom,

The dull of midnight, at her couch’s foot

Lorenzo stood, and wept: the forest tomb

Had marr’d his glossy hair which once could shoot [→ 209]

Lustre into the sun, and put cold doom

Upon his lips, and taken the soft lute

From his lorn voice, and past his loamed ears

Had made a miry channel for his tears. (ll. 273-80)8

Rossetti reworks this supernatural “vision” in at least two ways. Firstly, he alters the source of Keats’s “tears” so that they do not flow from the revenant- but the mourner-figure, falling “from octet into sestet” (Remoortel 468). And, secondly, he limns a portrait of the dead thoroughly cleansed of what “Isabella” elsewhere calls “wormy circumstance” (l. 385). Although Lorenzo retains “eyes [...] all dewy bright / With love” that keep “all phantom fear aloof” (ll. 289-90, 290), his experience of the “tomb” has otherwise taken its toll and results in disfigurements smoothed out and corrected in the fetching look of “Willowwood”’s returning and ebullient beloved: his “marr’d” “hair” is buoyantly restyled as an undulating Pre-Raphaelite coiffure, and “lips” laden with “cold doom” become the vibrant bearers, at the end of “Willowwood I,” of “brimming kisses.”

The second moment occurs in stanza 46 of Keats’s text, after Isabella has entered the “dismal forest-hearse” (l. 344) and kneels at the site of Lorenzo’s burial. Here, as “[s]he gaz[es] into the fresh-thrown mould” (l. 361) that composes his grave, “fully” seeing “all its secrets” at “[o]ne glance” (l. 362), her x-ray-like ocular powers are compared to those possessed by “other eyes” that “would know / Pale limbs at bottom of a crystal well” (ll. 363, 363-64). In “Willowwood I,” however, the simile is reversed, as still other eyes (those of Rossetti’s weeping speaker) peer into a well that seems like a grave, rather than a grave that seems like a well.

The third moment is located in stanzas 50-51, as Keats’s mourner, assisted by her “old nurse” (l. 377), severs Lorenzo’s head from his body and carries off the grisly spoils:

With duller steel than the Perséan sword

They cut away no formless monster’s head,

But one, whose gentleness did well accord

With death, as life. The ancient harps have said, [→ 210]

Love never dies, but lives, immortal Lord:

If love impersonate was ever dead,

Pale Isabella kiss’d it, and low moan’d.

’Twas love; cold,—dead indeed, but not dethroned.

In anxious secrecy they took it home,

And then the prize was all for Isabel:

She calm’d its wild hair with a golden comb,

And all around each eye’s sepulchral cell

Pointed each fringed lash; the smeared loam

With tears, as chilly as a dripping well,

She drench’d away:—and still she comb’d, and kept

Sighing all day—and still she kiss’d, and wept. (ll. 393-408)

Rossetti’s speaker is no Perseus, but it is nonetheless the case that the vision he conjures up in “Willowwood I” focuses exclusively on his dead beloved’s head—which can perhaps be seen to have a Medusan aspect to it—as if he has performed a metaphorical version of the decapitation that is here so abruptly literal. But while the scene in Keats has affinities with that in Rossetti, there are some salient differences. In Rossetti’s sonnet, the beloved’s head is fully revivified—returning “alive from the abyss,” as “Willowwood II” puts it (l. 10)—whereas in Keats’s poem there is no doubt that the “love impersonate” whom “[p]ale Isabella kiss[es]” is “dead indeed.” Even so, she does her best to make Lorenzo’s appearance more lifelike by grooming and cosmeticising it: she incessantly combs his “wild hair,” “[p]oint[s]” his eyelashes and washes away the “loam” “smeared” over his face with “tears” that are, ironically, “as chilly as a dripping well.”

A sense of how “Willowwood” echoes “Isabella” beyond the opening sonnet can be gleaned, first of all, by taking a fresh look at the three phrases previously cited from “Willowwood II.” As already suggested, one of the ways of reading the first of these (“meshed with half-remembrance”) is to see it as a shorthand for “Willowwood”’s intertextual memory of “Isabella” in general. Equally, though, the phrase can be viewed as providing a specific example of that memory at work, recalling stanza 58 of Keats’s poem. Here Isabella’s “brethren,” unaware that she now knows about Lorenzo’s murder and is herself dying of [→ 211] grief, are mystified by the spell the “[b]asil-pot” has cast over their sister—a charm so strong, they surmise, as to have distracted her from Lorenzo’s absence on the business he is supposedly carrying out on their behalf in “foreign lands” (l. 457, 473, 226). As the poem puts it:

They could not surely give belief, that such

A very nothing would have power to wean

Her from her own fair youth, and pleasures gay,

And even remembrance of her love’s delay. (ll. 461-64)

The second phrase (“those [...] days that had no tongue”) looks back to “Isabella”’s first six stanzas and the point in the narrative when the love between Isabella and Lorenzo is already “[f]ever’d” and yet denied sexual expression by dint of how Lorenzo repeatedly defers until “[t]o-morrow” the opportunity to make his feelings known, letting “[h]oneyless days and days” (ll. 46, 27, 32) slip by. The narrator comments:

all day

His heart beat awfully against his side;

And to his heart he inwardly did pray

For power to speak; but still the ruddy tide

Stilled his voice, and puls’d resolve away. (ll. 41-5)

As these lines suggest, Isabella’s memory of “her love’s delay” is thus not just to do with an overdue return from a spurious trip abroad, but reaches back to the tongue-tied ordeal which Lorenzo suffers at the poem’s outset and that reduces him to a state of “sick longing” (l. 23). That tongue-tiedness is in turn recalled in “Willowwood II,” as the speaker remembers and laments the times when he and his beloved did not or could not communicate with one another, enduring “days” that were similarly bereft of verbal exchange.

The third phrase (“alive from the abyss”) takes the reader to stanza 40 of Keats’s poem and to Lorenzo’s valedictory address to Isabella, just before her dream dissolves, in which he figures her as “[a] Seraph [. . .] from the bright abyss” whom he has “chosen” “[t]o be [his] spouse” (ll. [→ 212] 317, 318). This is an image that “Willowwood” turns upside down, associating the space from which its speaker’s own spouse reappears not with airy and seraphic heights but aquatic and regenerative depths, which Marianne van Remoortel describes as “amniotic” (470). As Keats’s narrator notes in stanza 36, one of the effects of Lorenzo’s murder is to make his voice sound “[s]trange,” such that when it speaks from beyond the grave it seems accompanied by a “ghostly under-song” (ll. 281, 287). But “Isabella” is itself, it might be said, such an accompaniment and undersong to “Willowwood,” as Keats’s own poetic voice returns in these sonnets in distorted form.

While “Willowwood” announces the beginning of Love’s “song” in the first line of its second sonnet, it is not until the first line of its third that the song itself becomes finally “audible.” Despite being “hard to free” (“Willowwood II” l. 2) from “half-remembrance,” the song has, it seems, been temporarily (and ironically) forgotten:

‘O ye, all ye that walk in Willowwood,

That walk with hollow faces burning white;

What fathom-depth of soul-struck widowhood,

What long, what longer hours, one lifelong night,

Ere ye again, who so in vain have wooed

Your last hope lost, who so in vain invite

Your lips to that their unforgotten food,

Ere ye, ere ye again shall see the light!

Alas! The bitter banks in Willowwood,

With tear-spurge wan, with blood-wort burning red:

Alas! If ever such a pillow could

Steep deep the soul in sleep till she were dead,—

Better all life forget her than this thing,

That Willowwood should hold her wandering!’ (“Willowwood III” ll. 1-14)

With its multiple exclamations and inclusiveness of address, this song sounds more like the proclamation of a town crier than a personified Love, and one who is prepared, moreover, to take audacious verbal risks (rhyming “Willowwood” with “pillow could,” for example) and to emphasise his message with the sonnets’ only closing couplet. And perhaps it is that message that accounts for the belatedness of the song’s [→ 213] appearance on the textual scene, since it is one the speaker might be reluctant to hear or heed. At this juncture, he is in the same attitude as in “Willowwood I,” still “stoop[ing]” to kiss his late wife—or at least her ardent simulacrum, as it “ris[es]” from the abysmal well to meet him face-to-face—“invit[ing]” his own “lips” to feast upon hers as if the latter were an “unforgotten food.” Yet in cleaving to this visionary figure in this self-gratifying way, the speaker adopts an approach to his bereavement that is at loggerheads with Love’s severe counsel that, in the end, it is “[b]etter” “to forget” the one he mourns—permanently, if necessary—than to court the “vain” “hope” that they will again meet one another in any sphere beyond that forged by “the longing fancy.” To entertain such a possibility is to join the ranks of those distracted somnambulists who “walk in Willowwood, / [...] with hollow faces burning white,” entering a place that is not in fact a place at all but a potentially self-destructive psychological state defined by a mixture of grief, self-delusion and emotional fixation. This indeed is the kind of anguished condition in which the lachrymose Isabella is to be found in the wake of Lorenzo’s death as, rather than obliterating the memory of her lover for “all life,” she obliterates the memory of “all life” for her lover:

And she forgot the stars, the moon, and sun,

And she forgot the blue above the trees,

And she forgot the dells where waters run,

And she forgot the chilly autumn breeze. (ll. 417-20)

In her reading of “Willowwood I,” Isobel Armstrong draws attention to that sonnet’s predilection for the “l” consonant. This phonetic unit, she writes, “appears in almost every line [...] as if the poem is afloat in the medium of [its] liquid sounds” (466). Such consonantal saturation is yet more noticeable in “Willowwood III,” but in this sonnet the “l” sound competes for primacy with “w,” with both phonemes featuring in the opening “well,” which, in turn, and at the risk of repetition, contains an echo of “Howell.” The soundscape of this sonnet, that is, provides another cryptic or cryptographic example of “Willowwood”’s [→ 214] prefigurative link with the exhumation. Such a link is further evidenced by the metaphorical “pillow” which enters the sonnet’s sestet and is infused with the power to “[s]teep deep the soul in sleep till she were dead.” This uncanny item, complete with its hypnotic and murderous play of assonance and sibilance, looks forward to the wishfulness of the letter to Swinburne, in which Rossetti imagines Siddal as ghostly handmaiden, returning his “book” to him on “the night she was buried” and placing it, in her own cryptic gesture, on a “pillow” that is this time literal.

Yet as much as it creates anticipatory links with that letter, the pillow featured at line eleven of this sonnet also establishes retrospective connections with “Isabella.” In stanza 4 of that poem, for example, both Lorenzo and Isabella use pillows of their own as a means of confessing the feelings they cannot confess to one another:

‘To-morrow will I bow to my delight,

To-morrow will I ask my lady’s boon.’—

‘O may I never see another night,

Lorenzo, if thy lips breathe not love’s tune.’—

So spake they to their pillows […]. (ll. 27-31)

And in stanza 41 yet another pillow appears, as the narrator strives to capture the sense of visual disturbance produced by Lorenzo’s ghost as he withdraws himself from Isabella’s dream:

The Spirit mourn’d ‘Adieu!’—dissolv’d, and left

The atom darkness in a slow turmoil;

As when of healthful midnight sleep bereft,

Thinking on rugged hours and fruitless toil,

We put our eyes into a pillowy cleft,

And see the spangly gloom froth up and boil. (ll. 321-26)

In this instance, the pillow in question is paradoxical, exacerbating insomnia by surely keeping weary “eyes” awake as the “spangly gloom” revealed in its “cleft” “froth[s] up” and “boil[s]” before them. Either way, it takes its place alongside the other pillow-images adduced above, as one more indication of Rossetti’s sonnets and Keats’s poem as intertextual bedfellows. [→ 215]

Although “Willowwood IV” begins with the rather curt or dismissive “[s]o sang he,” the action of the octet unfolds in accordance with Love’s bitter injunction to “forget” the beloved rather than continue to hold on to her:

So sang he: and as meeting rose and rose

Together cling through the wind’s wellaway

Nor change at once, yet near the end of day

The leaves drop loosened where the heart-stain glows,—

So when the song died did the kiss unclose;

And her face fell back drowned, and was as grey

As its grey eyes; and if it ever may

Meet mine again I know not if Love knows. (ll. 1-8)

Here the fading of Love’s “song” is simultaneous with the termination of the spouses’ “kiss” and the reabsorption of the beloved into the water from which she had initially emanated. As a result of the vision’s dissolution, it is implied, the speaker is able to escape the terrifying emotional petrification symbolised by Willowwood. In so doing, he also implicitly avoids the grief-stricken insanity that overtakes the dying Isabella at the end of Keats’s poem, as she cossets Lorenzo’s “fast mouldering head,” feeding with constant “tears” the “[b]asil sweet” that grows over and out of it, before her brothers rob her of her reliquary and the “jewel” (ll. 430, 425, 488, 431) it contains once and for all.

As Rossetti’s fourth and final sonnet closes, however, there are indications that the divorce between speaker and beloved is less clear-cut than it might seem:

I leaned low and drank

A long draught from the water where she sank,

Her breath and all her tears and all her soul:

And as I drank I know I felt Love’s face

Pressed on my neck with moan of pity and grace,

Till both our heads were in his aureole. (ll. 9-14)

While he may have given up the “food” that the beloved’s lips and kisses once proffered him, it is only to incorporate her all the more greedily, taking “[a] long draught from the water where she sank” and [→ 216] gulping down “[h]er breath and all her tears and all her soul.” The sense of unity rather than separation that these lines evoke is supported by the way in which the speaker’s posture at this point—he is “lean[ing] low” over the well—mirrors the position he was in at “Willowwood”’s beginning, where he “[l]ean[s] across the water,” as if the “Willowwood” sequence were actually a cycle (and sonnets one and four have an identical rhyme scheme). That sense of unity is also underscored by the ambiguous closing image of the “heads” included in Love’s “aureole.” To whom do these heads belong? Are they those of the speaker and Love himself, alone together once again as they were prior to the onset of the vision, as would seem to be the obvious meaning? Or can they be assigned to the speaker and the beloved, as if the latter had somehow survived or defied the drowning to which “Willowwood IV” subjects her?

It would perhaps be overingenious to suggest that there is also space in Love’s “aureole” for the intertextual memory of Lorenzo’s head, but “Willowwood IV” includes some three rather more definite echoes of “Isabella.” The first can be unearthed by returning to the speaker’s comprehensive last-gasp incorporation of his late wife’s “breath,” “tears” and “soul,” an image which itself returns to and incorporates Lorenzo’s thirsty vow, in stanza 5 of Keats’s poem, to “drink” Isabella’s “tears” (l. 39). The second takes the more incidental form of Rossetti’s invocation of the “wind’s wellaway,” an archaic turn of phrase indebted to stanza 61 of “Isabella” and the narratorial instruction to the “Spirits in grief” that have been silently assembling on the poem’s margin since stanza 55: “sing not your ‘Well-a-way!’ / For Isabel, sweet Isabel, will die” (ll. 437, 485-86). The third and most significant echo involves the rose-simile trellised across the sonnet’s first five lines. This is a conceit that Rossetti has transplanted, once more, from “Isabella” and, specifically, stanza 10:

Parting they seem’d to tread upon the air,

Twin roses by the zephyr blown apart

Only to meet again more close, and share

The inward fragrance of each other’s heart. (ll. 73-6) [→ 217]

But while Rossetti’s simile recalls or “meet[s]” with Keats’s, it revises the original in one important respect: in Keats, the roses are “blown apart” from one another only to be rejoined, whereas, in Rossetti, the opposite is the case, as the flowers at first “cling” valiantly “[t]ogether” against the wind’s ominous cry but eventually and inevitably are torn asunder.9

In its echoes and reworkings of “Isabella,” “Willowwood IV” conforms to the pattern of the three sonnets that precede it, as Rossetti takes up a range of threads from Keats’s poem and weaves them into his own textual tapestry. But the sonnet also provides more signs of “Willowwood”’s sotto voce links with the exhumation episode. In addition to its Keatsian echo, Rossetti’s “wellaway” is still another verbal reminder of the shadowy Howell, while the “grey eyes” and “grey face” of the “drowned” beloved look forwards—even as they recede and disappear—to the tantalising manuscript, “bound in rough grey calf,” that Rossetti will reach out to repossess.

Conclusion

As Federica Mazzara phrases it, Rossetti’s letters are an “unexplored world” (115), rarely attracting the kind of sustained close analysis that this article has sought to offer and that seems particularly exigent when it comes to Rossetti’s exhumation of his poems, given the degree to which, rightly or wrongly, “[t]o many [...] this act defines” the artist-poet “and has never been forgiven” (Marsh, “Grave” 14). One advantage of so closely tracking Rossetti’s epistolary representation of this episode is that it throws into relief the conflicts, disavowals and contradictions it induces in the one it most concerns. It allows the reader to think through the evolution and immediate aftermath of the episode from something akin to what Rossetti, writing of “Jenny,” calls an “inner standing-point” (“Stealthy” 337; italics in original) and thus adds fresh texture to our understanding of what is the most egregious incident in Rossetti’s biography and mid-Victorian literary history more broadly. [→ 218]

Together with providing new perspectives on the disinterment (including its relationship with Clerk Saunders), the article has endeavoured to alter the angle of critical vision with respect to “Willowwood.” In diametric contrast to Rossetti’s letters, these sonnets have been critically much-traversed but still have their reserve of secrets and surprises, taking the form of the links with the events in Highgate, on the one hand and, on the other, with “Isabella,” Keats’s own hide-and-seek tale of alternating burials and exhumations, as discussed in this article’s second section. As it exposes these clandestine connections—and draws out the instabilities and slippages in Rossetti’s writing of the disinterment in his letters—the article implicitly casts the practice of reading in a different light, suggesting that perhaps it too, under certain circumstances, can be considered a kind of exhumation in itself.

Figures

Fig. 1 Elizabeth Eleanor Siddal, Clerk Saunders (1857). Watercolour, body colour, coloured chalks on paper laid on a stretcher. 28.4 x 18.1 cm. Cambridge, Fitzwilliam Museum. Photograph @The Fitzwilliam Museum, University of Cambridge.

https://data.fitzmuseum.cam.ac.uk/id/object/13598

Fig. 2. William Holman Hunt, Isabella and the Pot of Basil (1866-68). Oil on canvas. 187 x 116.5 cm. Tyne and Wear Archives & Museums/Bridgeman Images.

Works Cited

Angeli, Helen Rossetti. Pre-Raphaelite Twilight: The Story of Charles Augustus Howell. London: Richards, 1954.

Armstrong, Isobel. “D. G. Rossetti and Christina Rossetti as Sonnet Writers.” Victorian Poetry 48.4 (Winter 2010): 461-73.

Baum, Paull Franklin. The House of Life: A Sonnet-Sequence by Dante Gabriel Rossetti. Cambridge, MA: Harvard UP, 1928.

Bronfen, Elisabeth. Over Her Dead Body: Death, Femininity and the Aesthetic. Manchester: Manchester UP, 1992.

Bronkhurst, Judith. “William Holman Hunt.” The Pre-Raphaelites. Ed. Leslie Parris. London: Tate Gallery, 1994. 216-18.

Bullen, J. B. “Raising the Dead: Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s ‘Willowwood’ Sonnets.” The Oxford Handbook of Victorian Poetry. Ed. Matthew Bevis. Oxford: OUP, 2013. 429-44.

Bullen, J. B., Rosalind White, and Lenore A. Beaky, eds. Pre-Raphaelites in the Spirit World: The Séance Diary of William Michael Rossetti. Oxford: Peter Lang, 2022.

“Clerk Saunders.” Minstrelsy of the Scottish Border, with Notes and Introduction by Sir Walter Scott. Vol. 3. Rev. and ed. T. F. Henderson. Edinburgh: Oliver and Boyd, 1932. 222-29.

Cline, C. L., ed. The Owl and the Rossettis: Letters of Charles A. Howell, Dante Gabriel, Christina, and William Michael Rossetti. University Park: Pennsylvania State UP, 1978.

Cole, Mark. “A Haunting Portrait by William Holman Hunt.” Bulletin of the Cleveland Museum of Art 77.10 (December 1990): 354-65.

Drew, Rodger. The Stream’s Secret: The Symbolism of Dante Gabriel Rossetti. Cambridge: Letterworth, 2007.

Dunstan, Angie. “Stunner: Elizabeth Siddal, the Evolution of a Sensation.” Literature and Sensation. Ed. Anthony Uhlmann et al. Newcastle-upon-Tyne: Cambridge Scholars, 2009. 24-33.

Eliot, T. S. “Eyes That Last I Saw in Tears.” The Complete Poems and Plays of T. S. Eliot. London: Faber, 1969. 133.

Freud, Sigmund. “Mourning and Melancholia.” The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud. Vol. 14. Trans. James Strachey et al. London: Hogarth, 1957. 239-58.

Keats, John. “Isabella; or, The Pot of Basil.” John Keats: The Major Works. Ed. Elizabeth Cook. Oxford: OUP, 1990. 185-201.

Leighton, Angela. “Buried Deep: The Wandering Ghosts behind Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s Words.” Times Literary Supplement 5394 (18 and 25 Aug. 2006): 3-4.

Lutz, Deborah. Pleasure Bound: Victorian Sex Rebels and the New Eroticism. New York: Norton, 2011.

Lutz, Deborah. Relics of Death in Victorian Literature and Culture. Cambridge: CUP, 2015.

Marsh, Jan. “Grave Doubts: Dante Gabriel Rossetti and the Exhumation Poems.” Times Literary Supplement 5681 (17 February 2012): 14-15.

Marsh, Jan. The Legend of Elizabeth Siddal. 2nd ed. London: Quartet, 2010.

Marvell, Andrew. “To His Coy Mistress.” The Poems of Andrew Marvell. Ed. Nigel Smith. Rev. ed. London: Pearson Education, 2007. 81-84.

Matthews, Samantha. Poetical Remains: Poets’ Graves, Bodies, and Books in the Nineteenth Century. Oxford: OUP, 2004.

Mazzara, Federica. “Rossetti’s Letters: Intimate Desires and ‘Sister Arts.’” Interfaces: Image Texte Language 28 (2008-09): 115-24.

McGann, Jerome. “Scholarly Commentary.” Rossetti Archive. http://www.rossettiarchive.org/docs/14-1869.raw.html. 27 Jan 2024.

Reeve, Nat. “‘An Hour before the Day’: The Dismembered Book of Hours in Elizabeth Siddal’s Clerk Saunders.” Word & Image 38.2 (2022): 73-87.

Remoortel, Marianne van. “Metaphor and Maternity: Dante Gabriel Rossetti’s ‘House of Life’ and Augusta Webster’s ‘Mother and Daughter.’” Victorian Poetry 46.4 (Winter 2008): 467-86.

Rossetti, Christina. “Death.” Christina Rossetti: The Complete Poems. Ed. R. W. Crump; with notes and intr. by Betty S. Flowers. London: Penguin, 2005. 688-89.

Rossetti, Dante Gabriel. Collected Poetry and Prose. Ed. Jerome McGann. New Haven: Yale UP, 2003.

Rossetti, Dante Gabriel. The Correspondence of Dante Gabriel Rossetti. Ed. William E. Fredeman. Vol. 4: The Chelsea Years, 1863-1872: Prelude to Crisis, 1868-70. Cambridge: Brewer, 2004.

Rossetti, Dante Gabriel. The House of Life: A Sonnet-Sequence by Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Variorum Edition with an Introduction and Notes. Ed. Roger C. Lewis. Cambridge: Boydell & Brewer, 2007.

Rossetti, Dante Gabriel. “Jenny.” Collected Poetry and Prose. Ed. Jerome McGann. New Haven: Yale UP, 2003. 60-69.

Rossetti, Dante Gabriel. “Life-in-Love.” Collected Poetry and Prose. Ed. Jerome McGann. New Haven: Yale UP, 2003. 143.

Rossetti, Dante Gabriel. “Preface.” The Early Italian Poets from Ciullo D’Alcamo to Dante Alighieri (1100-1200-1300) in the Original Metres, Together with Dante’s Vita Nuova. London: Smith, Elder and Co., 1861. Vii-xii.

Rossetti, Dante Gabriel. “The Stealthy School of Criticism.” Collected Poetry and Prose. Ed. Jerome McGann. New Haven: Yale UP, 2003. 335-40.

Rossetti, Dante Gabriel. “Willowwood.” Fortnightly Review 27 (new series) (1 March 1869): 266-67.

Rossetti, Dante Gabriel. “Willowwood.” The House of Life. Ballads and Sonnets. London: Ellis, 1881. 211-14.

Rossetti, Dante Gabriel. “Willowwood.” The House of Life. Poems. London: Ellis, 1870. 212-15.

Rossetti, Gabriele. A Versified Autobiography. Trans. William Michael Rossetti. London: Sands & Co., 1901.

Rossetti, William Michael. Dante Gabriel Rossetti: His Family-Letters with a Memoir. 2 vols. Boston: Roberts Brothers, 1895.

Scott, William Bell. Autobiographical Notes of the Life of William Bell Scott: And Notices of His Artistic and Poetic Circle of Friends, 1830 to 1882. Vol. 2. Ed. W. Minto. New York: Harper & Brothers, 1892.

Shonfield, Zuzanna. The Precariously Privileged: A Professional Family in Victorian London. Oxford: OUP, 1987.

Symons, Arthur. “The Rossettis: Dante Gabriel and William Michael—and Their Friendship with Meredith and Swinburne.” Vanity Fair 12.3 (May 1919): 51-70.

Troxell, Janet Camp, ed. Three Rossettis: Unpublished Letters to and from Dante Gabriel, Christina, William. Cambridge, MA: Harvard UP, 1937.