"Mistah Kurtz—he dead" in Company: Redundancy and Ellipsis

William Harmon

Published in Connotations Vol. 21.2-3 (2011/12)

Let me start with five texts that have a good deal in common and try to proceed inductively to arrive at some general observations about poetic economy. The choice of this material was prompted by the announcement of the topic for the 2011 meeting of the Connotations Society-"Poetic Economy: Ellipsis and Redundancy in Literature." My starting point was: Lexical lists typically involve redundancy, repetition, and reduplication; syntactic strings typically involve ellipsis and dissimilation. Against this background, I would like to focus on five particularly interesting specimens of redundancy, ellipsis, or both together:

"THY, DAMNATION, SLUMBERETH, NOT"

"Softly, softly, catchee monkey"

"Mithridates, he died old"

"Mistah Kurtz-he dead"

"Long time no see"

These are arranged chronologically from 1891 to 1900. Two come from prose fiction, two from prose non−fiction, and one from poetry. All represent utterances spoken by rustic, marginal, or liminal characters, sometimes in liminal situations; all have some association with a western region; and all happen to be four words long. Those temporal, social, and geographic points of resemblance have prompted me to speculate about the general properties of what structural linguists have called "the axis of selection" and "the axis of combination," and in particular about Roman Jakobson's notion that poetry (or "the poetic function" in general) represents the projection of the properties of the axis of selection onto the axis of combination.1) Such projection constitutes a provisional definition of one sort of poetic economy. Ordinary discourse favors the horizontal, successive, or syntagmatic presentation of language, which is the norm of speech and prose. Extraordinary discourse favors the vertical, simultaneous, or paradigmatic display of language, which is the norm of most poetry and some poetic prose. Discourse in general combines both dimensions, and what is called the "poetic function" is a matter of relative preponderance and not of anything absolute or exclusive.

The sources of the five exemplary utterances are Thomas Hardy's Tess of the d'Urbervilles (79; orig. published 1891), R. S. S. Baden−Powell's The Downfall of Prempeh: A Diary of Life with the Native Levy in Ashanti 1895−96 (13; 1896), A. E. Housman's A Shropshire Lad (poem LXII; 1896), Joseph Conrad's Heart of Darkness (78; original magazine publication 1899), and W. F. Drannan's Thirty−One Years on the Plains and in the Mountains: Or, the Last Voice from the Plains (514−15; 1900).2) The settings are in a western region of England, Africa, and the United States. Much of Hardy's Wessex is included in what is now known as South West England; Baden−Powell's Ashanti is now in Ghana in West Africa; Housman's Shropshire is in the West Midlands, on the border between England and Wales; Heart of Darkness, although it rather coyly avoids saying "Brussels" or "Belgium" or any specific place in Africa, is clearly set in what was then called the Congo Free State (now, after several changes, the Democratic Republic of the Congo); and Drannan's supposed encounter with Captain Jack, the Modoc chief, took place near Yreka, in north central California. Captain Jack had been hanged for murder in 1873.3)

"THY, DAMNATION, SLUMBERETH, NOT" (especially in homely oversized red capitals) displays the redundancy of unnecessary commas that convert the string of the scriptural sentence (an adaptation of 2 Peter 2:3: "Their damnation slumbereth not") into a virtual list of equally spaced items. "Softly, softly, catchee monkey" and "Long time no see" both involve ellipsis of the subject and omission of articles, prepositions, and pronouns, as well as certain lexical repetitions and deformations. The lexical repetitions are reinforced acoustically by syllabic patterning (four trochees, four stressed monosyllables). "Mithridates, he died old" and "Mistah Kurtz-he dead" both involve the common sort of redundancy known as "noun−pronoun pleonasm." "Mistah Kurtz-he dead," furthermore, also involves ellipsis of the verb, for which the full form and its paraphrase would be "he is dead," "he died," or "he has died." Moreover, "Softly, softly, catchee monkey" and "Mistah Kurtz-he dead" involve both redundancy and ellipsis of one sort or another.

It is also possible that the omission of the copula "is" between "he" and "dead" represents not an error but a common feature of many languages, including Hebrew, Chinese, and several West African dialects. It is interesting that Conrad's Nigger of the "Narcissus" uses eye dialect and misspelling for the speech of a villainous white character Donkin: "The ragged newcomer was indignant-'That's a fine way to welcome a chap into a fo'c'sle,' he snarled. 'Are you men or a lot of 'artless cannybals?'"(14).

The quotations from Hardy, Housman, and Conrad are from canonical literary texts, two from fiction and one from poetry.4) Those from non−fiction prose texts by Baden−Powell and Drannan represent the earliest record of vernacular expressions that probably date from some earlier period but have not been attested.5) Moreover, these five four−word texts from 1891−1900 represent the utterance of a socially marginal or marginalized personage. The utterance in Tess of the d'Urbervilles is the work of an eccentric itinerant painter of religious graffiti on outside surfaces, in red capitals with commas after every word "as if to give pause while that word was driven well home to the reader's heart" (88). Baden−Powell's saying comes from "The Author's Apology to the Reader": "I will here at once say that the moral may be summed up thus. A smile and a stick will carry you through any difficulty in the world, more especially if you act upon the old West Coast motto, 'Softly, softly, catchee monkey'" (13). The quotation from Housman is the utterance of Terence Hearsay, the Shropshire Lad himself. In Heart of Darkness, the four−word obituary is spoken "in a tone of scathing contempt" by "the manager's boy" (77). Drannan's quotation-actually in the five−word form "Long time no see you"-is spoken by Captain Jack, "the chief of the Modoc tribe" who "made a very good stagger towards talking the English language" (481). In any event, two of the speakers are so−called natives and three are obvious rustics with little schooling. That is, they are, in their original contexts, marginal figures in a marginal situation on a margin of civilization.

All five utterances exhibit some kind of departure from the normal syntactic "string" of discourse, so that the customary horizontal flow is somehow interrupted and, partly at least, reverts instead to the status of a vertical "list." In other words-words drawn from such structural linguists as Ferdinand de Saussure and Roman Jakobson6)-what should be arrayed on the syntagmatic axis of combination behaves more like what is usually arrayed on the paradigmatic axis of selection. This shifting of poles, so that the habits of the axis of selection are projected onto the axis of combination, is defined by Jakobson as the hallmark of the "poetic" function of language, with "poetic" often extended to include "literary" and "aesthetic" (in "Closing Statements: Linguistics and Poetics"). Paradigmaticity, as it were, can convert any ostensibly syntagmatic string into a virtual poem.

The rearrangement in the quotations can be represented graphically. Thanks to the redundant commas, "THY, DAMNATION, SLUMBERETH, NOT" (originally in large red capitals) becomes

THY,

DAMNATION,

SLUMBERETH,

NOT.

What we call noun−pronoun pleonasm is common in both formal and informal situations ("Thy rod and Thy staff, they comfort me"). The quotations from Housman and Conrad, very similar in structure and substance, become

Mithridates,

he died old,

and

Mistah Kurtz-

he dead.

And the dissyllabic and monosyllabic formulations from Baden−Powell and Drannan become

Softly,

softly,

catchee

monkey

and

Long

time

no

see.

In most printed poems, especially those with rhyme, measured lineation may suggest a vertical dimension, although most lines are printed horizontally with an unjustified right margin. Some poems graphically represent such an array, as in Pound's Canto LI:

Shines

in the mind of heaven God

who made it

more than the sun

in our eye. (Cantos 250)

Here the extra spaces after "heaven" and the short lines underscore the resonant effect of the long vowel in "Shines," "mind," and "eye." Similar quasi−paradigms occur in Canto LXXVIII:

there

are

no

righteous

wars (497)

and Canto LXXIX:

aram

nemus

vult

(506)

Likewise with many of E. E. Cummings's layouts:

l(a

le

af

fa

ll

s)

one

l

iness (673)

In some prose, even without any reliance on layout, a rhythm of lexical and acoustic repetitions suggests a paradigmatic axis:

Dencombe lay taking this in; then he gathered strength to speak once more. "A second chance-that's the delusion. There never was to be but one. We work in the dark-we do what we can-we give what we have. Our doubt is our passion and our passion is our task. The rest is the madness of art." (Henry James, "The Middle Years" 105; emphasis in original)

My observations here have spun off from a project I began some years ago that was stimulated by aimless miscellaneous reading. I probably started with the morphological notion of the complementary relation between reduplication and dissimilation.7) Reduplication is a morpho-logical doubling to indicate a change of meaning, as between present and perfect (Latin do "I give" versus dedi "I have given"). Dissimilation is a modification of sounds to avoid repetition, as between earlier "femininist" and "pacificist," on the one hand, and later streamlined "feminist" and "pacifist." Sometimes spelling remains constant but pronunciation may dissimilate, as when "chimney" is sounded "chimbly" or "chiminee" (both avoid the repeated voiced nasals in mn). Earlier Latin medīdiēs "mid−day" was dissimilated into merīdiēs, surviving in such modern forms as "meridian."

The contrast of reduplication and dissimilation is at some point connected with Jakobson's model of the poetic function. Other homologous binary sets include metaphor versus metonymy (important to Jakobson), synchrony versus diachrony (important to Saussure and many others), simultaneous versus successive (important to Lessing), charisma versus bureaucracy (important to Max Weber), and redundancy versus ellipsis (important to Connotations).

For a while, I entertained a three−tiered model of discourse, whereby a level of ordinary dissimilation is flanked by layers of extraordinary reduplication (with onomatopoeia on one side and proper names on the other; cf. my essay on "Bash? and Proust"). In poetry, the intellectual and emotional message may be stated as discourse, but the ritual significance is suggested by extraordinarily redundant onomatopoeia ("Jug Jug," "Twit twit twit ⁄ Jug jug jug jug jug jug," "Drip drop drip drop drop drop drop," "Co co rico co co rico," "DA"), exclamations and informal speech or echoic song ("O O O O," "Ta ta," "Weialala leia ⁄ Wallala leialala la la"), reduplicative names ("Sosostris"), and lexical repetition ("Burning burning burning burning," "swallow swallow," "Datta. Dayadhvam. Damyata. ⁄ Shantih shantih shantih"; T. S. Eliot, The Waste Land passim).

And then, after I caught my breath, all that speculation crystallized untidily around a passage in Umberto Eco's The Name of the Rose, where the narrator names some colleagues working in an abbey library and adds: "The list could surely go on, and nothing is more wonderful than a list, instrument of wondrous hypotyposis" (73; "L'elenco potrebbe certo continuare e nulla vi è di più meraviglioso dell'elenco, strumento di mirabili ipotiposi" [218]). A list as such is paradigmatic, and its marvelousness may be a function of its appropriation of the poetic function (a concept no doubt familiar to Eco, a semiotician as well as a novelist).

Just how, I asked myself, can hypotyposis-the casting of a vivid image before the eye-be effected by a list? The list in The Name of the Rose is not in itself very vivid: "Thus I met Venantius of Salvemec, translator from the Greek and the Arabic, devoted to that Aristotle who surely was the wisest of all men. Benno of Uppsala, a young Scandinavian monk who was studying rhetoric. Aymaro of Alessandria […] and then a group of illuminators from various countries, Patrick of Clonmacnois, Rabano of Toledo, Magnus of Iona, Waldo of Hereford" (73).

It may be that both "elenco" and "ipotiposi" in the Italian original are technical terms, although "elenco" has been the more general, non−technical word for "list." Besides, one obsolete meaning of "elench" in English is "[a]n index, analytical table of contents." ("So Greek ἔλεγχος; compare Italian elenco, Spanish elenco in same sense"; OED, s.v. "Elench"). As it happens, the first use of that sense of "elench" is in John Foxe's Acts and Monuments of 1570 ("Certeine notes or elenchs upon this epistle"); and the first use of "hypotyposis" is in the same work, in a comment on Chaucer's "The Ploughman's Tale" ("Vnder whiche Hypotyposis or Poesie, who is so blind that seeth not by the Pellicane, the doctrine of Christ, and of the Lollardes to bee defended agaynst the Churche of Rome?"). In a peculiar way, Foxe's easy equation of "Hypotyposis" and "Poesie" prefigures Jakobson and Eco by about 400 years.

In later works, when Eco writes about lists, he uses "lista" (Vertigine della lista, The Vertigo of Lists, eventually in American English The Infinity of Lists). But I can imagine Eco and his translator William Weaver objecting that you won't have a best−seller if you use too many words like hypotyposis, elenchus, and vertigo.

But let us return to lists and strings in general. The graph of language production shows a vertical axis of selection, like a drop−down menu of options. At every point, a speaker selects an item from this axis, which is also called the paradigmatic axis. The paradigms are lists-some definite, some not-and a typical utterance, such as "Today is Thursday, August 4, 2011," represents a string of items chosen from lists, such as this:

Yesterdayhad beenSundayJanuary1TodaywasMondayFebruary22005Tomorrowhas beenTuesdayMarch32006isWednesdayApril42007will have beenThursdayMay52008will beFridayJune62009SaturdayJuly2010August312011September2012October2013NovemberDecember

At every point, the speaker chooses only one item. In passing, we might note that the paradigms are typically marked by certain repetitions of phonemes and morphemes-some items rhyme (Sun-day⁄Monday, January⁄February), some have the same ending (−day, −ber), some have the same beginning (Today⁄Tomorrow, March⁄ May, June⁄July), many have the same rhythmic pattern-and we don't mind that. Some items have even undergone reshaping to conform to a prevailing pattern: that is the case in English with "Wednesday," which is not pronounced Wed−nes−day but rather ⁄ˈwɛnzdeɪ⁄, ⁄ˈwɛnzˌdeɪ⁄, or⁄ˈwɛnzdɪ⁄, or "February," pronounced indeed by some ⁄ˈfɛbruːərɪ⁄ but metathesized by many, including me, into ⁄ˈfɛbr(ər)rɪ⁄, ⁄ˈfɛbjᵿri⁄, ⁄ˈfɛbjəʊri⁄, ⁄ˈfɛb(j)əˌwɛri⁄, ⁄ˈfɛbrəˌwɛri⁄, ⁄ˈfɛbuːrərɪ⁄ or ⁄ˈfɛbrərɪ⁄ (all from the OED). What is projected from the paradigmatic axis onto the syntagmatic axis is exceptional repetition of just the sort that speakers and writers usually avoid. The occurrence of some sort of lexical or acoustic repetition on an axis of combination, as in "Softly, softly, catchee monkey," arrests the customary horizontal flow and brings things to a momentary halt, as though to signal, "This is special: pay attention."

Repetitions, duplications, and reduplications are the norm on the paradigmatic axis. Verb paradigms in Latin, as we have seen above, sometimes contain a reduplicated preterite: cado−cadere−cecidi ("fall"), do−dare−dedi ("give"), tango−tangere−tetigi ("touch"), pango−pangere−pepigi ("fix, fasten"); such reduplications are known across the Indo−European spectrum. The norm of word formation in Indo−European languages tends to avoid repetition and stress difference. We stay away from repetitions like medīdiēs and reshape them into merīdiēs. I can testify that I feel awkward when I come to repeated elements in speech-in locutions like "edited it" and "statistics" and in occasional doublings such as "had had," "that that," and "her her" ("He handed her her hat"). These are not ungrammatical but they seem awkward to many speakers. Typical tongue−twisters involve an unusual degree of repetition ("Zehn zahme Ziegen zogen zehn Zentner Zucker zum Zoo"; "Peter Piper picked a peck of pickled peppers").

But in two areas we freely welcome repetition-in proper names (George, Barbara, Miami, Toronto, Jojo, Toto, Lulu, Mimi, Fifi, Gigi) and in uninflected onomatopoeia and exclamations (bow wow, quack quack, oink oink, gr−r−r−r, zzzzzzzzzzzz). "Barbara," indeed, can be a proper name but also ovine onomatopoeia (baa baa).8) We also make exceptions for baby talk and non−Indo−European words like "ukulele." An ancient sentiment among Indo−European speakers seems to oppose such reduplications in common, ordinary words, and also in syntactic strings (Cicero in Orator 47.158 calls reduplications "insuavius"). It is in such cases that we see the opposite of reduplication, which is dissimilation. Dissimilation works, sometimes over hundreds of years, to reduce or eliminate repetitions. That has happened to what begins millennia ago in Greek as something like marmar, then into Latin as marmor (subsequently borrowed into German), then into French as marbre, and on into English as marble, in which the second syllable -ble has completely dissimilated the earlier -mar. The replacements are rational: b for m remains in the bilabial group, l for r in the liquid.

In general, then, the axis of lexical lists and paradigms freely welcomes duplications and repetitions, but the axis of syntactic strings, even at the level of individual words, resists and opposes such repetitions. As we have seen, Roman Jakobson came to suggest that poetry, or the poetic function, involves the projection of the repetitive habits of the axis of selection onto the axis of combination, so that what ought to be a horizontal string-a line of poetry-may behave more like a vertical list. That is the case acoustically with monosyllabic "long time no see" and dissyllabic "softly, softly, catchee monkey." It is the case lexically with the noun−pronoun pleonasms in "Mithridates, he died old" and "Mistah Kurtz-he dead." With the painted inscription from Tess of the D'Urbervilles several factors contribute to the conversion of the syntagmatic "Thy damnation slumbereth not" into the quasi−paradigmatic "THY, DAMNATION, SLUMBERETH, NOT": the syllabic chiasmus (1−3−3−1), the bold capitals, the red paint, and the introduction of redundant commas, all of which stop traffic and arrest the forward linear motion of the utterance.

One awkward region in daily discourse has to do with consecutive possessives, which most speakers stumble over. This is an instance of reduplication on the syntagmatic axis, where it does not normally occur. Accordingly, it seems hard to say things like "my husband's cousin's funeral," because what ought to be syntagmatic threatens to become paradigmatic. But just such constructions can be an ornament of poetry, as the conclusion of Gerard Manley Hopkins's "The Wreck of the Deutschland" demonstrates:

Pride, rose, prince, hero of us, high−priest,

Our hearts' charity's hearth's fire, our thoughts' chivalry's throng's Lord.

(128)

We can see and hear the repeated consonants in pr−r−pr−h−h−pr and the echoes between "rose" and "hero," "hearts'" and "hearth's." "Chivalry" answers "charity," as "throng's" answers "thoughts." Alongside all these acoustic and lexical quasi−paradigms come the grammatical quasi−paradigms of two triple possessives, whereby the horizontal line of the sentence in effect tips over ninety degrees to become a most percussively emphatic paradigm.

This, then, may be what Adso of Melk, the narrator of Eco's The Name of the Rose, means when he calls a list "instrument of wondrous hypotyposis." Since a list is paradigmatic and not syntagmatic, it represents Jakobson's projection. Lists tend to elide verbs, which are the "time−words" in a sentence. Without verbs, time stands still for a list, so that the items seem to shine with their own radiance, a still point of a turning world-and that could be what generates "wondrous hypotyposis."

In this context it is interesting to look at William Weaver's translation of Eco. For one thing, it seems crudely echoic to put "wonderful" and "wondrous" so close together. (Although that is less crude than another version I have seen: "there is nothing more wonderful than a list, instrument of wonderful hypotyposis."9)) The original reads: "L'elenco potrebbe certo centinuare e nulla vi è di più meraviglioso dell'elenco, strumento di mirabili ipotiposi."

"Mirabili" does contain the element of wonder, but "meraviglioso" could be rendered by its cognate "marvelous." We might excuse a certain awkwardness, since this is after all the narrative of Adso, a naÏve Benedictine novice, although the work was supposedly not written or dictated until he was old. And we might take a cue from that very rare word "hypotyposis," for which the Oxford English Dictionary offers no example later than 1897. And I wonder, given a context that has room for "hypotyposis," if the repeated "l'elenco" might not be better rendered as "elench" or "elenchus," the English cognates, which are as rare as "hypotyposis"; we are, after all, witnessing the exercise of an apprentice scholastic who plays with the trendy vocabulary of 1327. So maybe the best translation would be "there is nothing more marvelous than an elenchus, instrument of wonderful hypotyposis."10)

This brings me to a paper I delivered in 2010 called "Strings That Move and Lists That Don't" for a conference devoted to "That Which Moves: The Kinetic Nature of Language and Literature," and, a little later, another paper called "Eliot: Lists, Tallies, Catalogues, Inventories, Paradigmata (Moments Minus Momentum)." And it was then that I received the Connotations Society's announcement about a conference devoted to "Poetic Economy: Ellipsis and Redundancy in Literature."

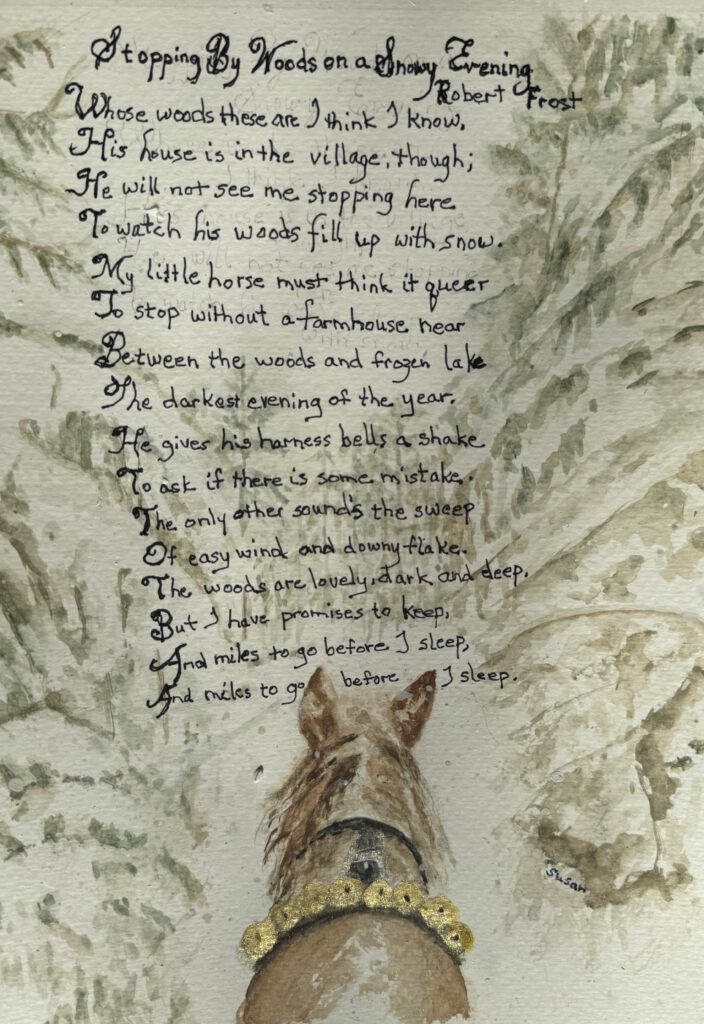

Well, I already had amassed more than enough material for seven or eight thirty−minute papers, and I even had a fairly long master list of lists from all over. I looked over my list of lists-with some pleasure, recalling Auden's self−indulgent poem "Lakes," which ends "Moraine, pot, oxbow, glint, sink, crater, piedmont, dimple …? ⁄ Just reeling off their names is ever so comfy" (563). I could feel much the same way about my list (though I doubt that I would ever say "comfy"): Homer, Ovid, Snorri Sturluson, Rabelais, Shakespeare, Milton, Doughty, Hopkins, Maugham, Frost, Stevens, Joyce, Pound, Eliot, T. E. Lawrence, Fitzgerald, Hemingway, Hart Crane, Nabokov, Borges, Salinger, Snyder, Updike, Pynchon… but I could also feel misgivings. How to get things down to a manageable paper?

By some fortuitous (and fortunate) visitation, I noticed that five items on my list stood out together: they all came from the same ten−year period (1891−1900), all were four words long, all presented some sort of syllabic symmetry, all represented diction somewhat removed from standard speech, and all could be associated with a western region. And all could be said to have achieved a special status. The dialectic of redundancy and ellipsis defines the essence of poetry and creates an extraordinary charismatic moment that stands out from its ordinary bureaucratic surroundings (in terms appropriated from Max Weber).11) An earlier obituary line from Poem LXII of Housman's A Shropshire Lad shows this operation clearly: "The cow, the old cow, she is dead," wherein the first six words constitute a paradigm of multiple noun−pronoun pleonasm:

The cow

the old cow

she-

the sort of thing from which we usually choose just one. Here, however, it is projected onto the axis of combination.

The cow

the old cow

she-

Without explicit predication, such a sentence may turn into a caption, motto, or slogan. The title of the first poem in Hardy's first book of poetry, "The Temporary the All," juxtaposes two abstractions, as though from a paradigmatic list, without overt predication, and the reader or hearer has to fill in what is missing from the ellipsis. It is not difficult to do, but it involves more active work than does passive reading. (Eco suggests that such interactive involvement is the purpose of hypotyposis: it is up to the reader to complete the picture that is begun with the mere list.12))

Only one specimen from the list-"Mithridates, he died old"-comes from a poem proper, but all the others stand out from their prose context, whether fiction or nonfiction-with the vivid distinctness of a poem. "Mistah Kurtz-he dead" would reappear as an epigraph to T. S. Eliot's "The Hollow Men" (and that is where I, for one, first encountered it); and "Long time no see" and "Softly, softly, catchee monkey" have taken on a life of their own in the vernacular, such that few speakers of English know where they may come from. Hardly a day goes by when you do not hear one or the other in public discourse or over a broadcast medium.

These specimens suggest that the most distinguished texts-those most literary and memorable-involve not just ellipsis or redundancy, not just an affair of lists or strings, but an artful combination of both. The context of "Mistah Kurtz-he dead," with its subtle mixture of redundancy and ellipsis, includes two other vivid four−word utterances spoken or written by Kurtz: "The horror! The horror!" (77) and "Exterminate all the brutes!" (55).

I suggest that certain types of redundancy and ellipsis may be related to contexts that involve such ideas as "western," "native," "rustic," "alterity," and "marginal"-all as possible sites of the poetic in many forms. The west of Britain was in some ways late to be subdued. The Roman, Danish, Saxon, and Norman invasions all occurred in the east and then pushed toward the west, driving the earlier Celtic peoples into enclaves in Cornwall, Wales, Scotland, the Isle of Man, and over into Ireland. This western boundary was possibly a "wild west" like that of America. Hardy's Wessex is defined by being western: it is the West Saxon realm, as Essex, Sussex, and Middlesex are the eastern, southern, and middle realms. Such an advancing frontier tests the theory, published by Frederick Jackson Turner in 1893, three years after the superintendent of the American census declared that the frontier was closed and the expansion complete, argued that the western frontier and the westward expansion explain the distinctive egalitarian, democratic, aggressive, and innovative features of the American character, along with uncouthness, rude humor, lawlessness, and general eccentricity. The Frontier Thesis, also the Turner Thesis, acknowledges how frontier life involves "breaking the bonds of custom, offering new experiences, and calling out new institutions and activities" (38). The bonds of custom may be so broken by marginal figures, such as an itinerant fanatic painting apocalyptic scriptures on stiles and walls and an unlettered versifier who has heard of Mithridates but has not heard of the rules governing pronouns. With Africa, the European encroachments moved from the outside in, but it remains possible that the western region in general retained its ruggedness after the relative urbanization of the east coast. With all three, the "West" provides a credible scene for a more robust exercise of human wit and resourcefulness, including pushing the limits of polite language.

It is possible to generalize that our five four−word texts have much in common. The authors of the texts themselves occupy a complex and ambiguous social space: a middle−class man writing about a working−class woman, an upper−class English officer among Africans, a middle−aged English scholar from Worcestershire writing in the voice of a country lad from Shropshire, a Pole writing in English about Belgians and Africans, and an aging bureaucrat inventing colorful stories of frontier life some decades in the past.

The temporal and spatial settings of all five utterances are somehow liminal, that is, they involve thresholds in time and space (the 1890s amounted to a liminal or transitional decade between centuries, a western frontier is a liminal place between levels of civilization and cultivation). Such figurative thresholds can be the powerfully charged scene of heightened meaning, so that what is spoken or written can take on extra symbolic or ritual significance. In some cases, the four−word utterance in a liminal setting becomes literally liminal: the text from Hardy is painted on a stile, that from Conrad is spoken in a doorway. With Baden−Powell and Housman, the liminal text comes at a liminal point in the work itself: the beginning of Baden−Powell's and the end of Housman's.13)

Let me end by sketching a further fanciful extension of those concepts. The norm of word formation in Indo−European languages tends to avoid repetition and stress difference. In certain extraordinary circumstances, however, locutions seem exempt from the usual protocols of dissimilation, as if a vertical paradigm arises out of the horizontal plane of discourse and demands attention for itself, in an act of what Foxe called hypotyposis−poesie. The proper names, you might say, are above the plane of discourse, the onomatopoeia and so forth below the plane. A total piece of discourse, then, would have the upper limit in proper names, the lower limit in raw noises, and possibly a center in a first− or second−person pronoun. Five examples (one of them was inspired by David Fishelov's brilliant paper at Freudenstadt, "The Economy of Literary Interpretation" during the 2011 Connotations Conference; forthcoming in Connotations 22):

Hwæt! We Gardena in geardagum

Matsushima ya!

Aa Matsushima ya!

Matsushima ya

Old MacDonald had a farm, EE−I−EE−I−O

Ave, Virgo! Gr−r−r-you swine!

pcheek pcheek pcheek pcheek pcheek

……

Our little lane, what a kingdom it was!

oi weih, oi weih 14)

Chapel Hill

Works Cited

Attridge, Derek. Peculiar Language: Literature as Difference from the Renaissance to James Joyce. London: Routledge, 2004.

Auden, W. H. Collected Poems. Ed. Edward Mendelson. New York: Vintage, 1991.

Baden−Powell, R. S. S. The Downfall of Prempeh: A Diary of Life with the Native Levy in Ashanti, 1895−96. London: Methuen, 1896.

Bate, W. N. Frontier Legend: Texas Finale of Capt. William F. Drannan, Pseudo Frontier Comrade of Kit Carson. New Bern, NC: Owen G. Dunn, 1954.

Cicero, Marcus Tullius. Ad M. Brutum Orator. Ed. John Edwin Sandys. New York: Georg Olms Verlag, 1973.

Conrad, Joseph. “The Heart of Darkness.” Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine Feb. 1899: 193−220. <https://archive.org/details/blackwoodsmagazi165edinuoft>.

Conrad, Joseph. “The Heart of Darkness.” Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine Mar. 1899: 497−502. <https://archive.org/details/blackwoodsmagazi165edinuoft>.

Conrad, Joseph. “The Heart of Darkness.” Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine Apr. 1899: 634−57. <https://archive.org/details/blackwoodsmagazi165edinuoft>.

Conrad, Joseph. Heart of Darkness. Heart of Darkness and Other Tales. Ed. Samuel Hynes. The Complete Short Fiction of Joseph Conrad. 4 vols. Vol. 3. London: Pickering & Chatto, 1993. 1−86.

Conrad, Joseph. The Nigger of the “Narcissus”: A Tale of the Sea. 1897. London: Heinemann, 1926.

Cummings, E. E. Complete Poems, 1904−1962. New York: Liveright, 1991.

Drannan, William F. Thirty−One Years on the Plains and in the Mountains: Or, the Last Voice from the Plains. Chicago: Rhodes & Mclure, 1900.

Eco, Umberto. Baudolino. Milan: Bompiani, 2000.

Eco, Umberto. Baudolino. Trans. William Weaver. New York: Harcourt, 2002.

Eco, Umberto. The Infinity of Lists: An Illustrated Essay. Trans. Alastair McEwen. New York: Rizzoli, 2009.

Eco, Umberto. The Name of the Rose. Trans. William Weaver. San Diego: Harcourt, 1983.

Eco, Umberto. Il nome della rosa. Milano: Bompiani, 1980.

Eco, Umberto. On Literature. London: Secker & Warburg, 2005.

Eco, Umberto. Postscript to The Name of the Rose. San Diego: Harcourt, 1984.

Eco, Umberto. Vertigine della Lista. Milano: Bompiani, 2009.

Eco, Umberto. The Vertigo of Lists: An Illustrated Essay. Trans. Alastair McEwen. Enfield: Publishers Group UK, 2009.

Eliot, T. S. The Waste Land. 1922. Ed. Stephen Coote. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1988.

Gennep, Arnold van. The Rites of Passage. 1909. Trans. Monika B. Vizedom and Gabrielle L. Caffee. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 1960.

Haggard, H. Rider. King Solomon’s Mines. 1885. Mattituck: Amereon House, 1981.

Hardy, Thomas. Tess of the d’Urbervilles: A Pure Woman. London: James R. Osgood, McIlvaine, 1891.

Hardy, Thomas. Tess of the d’Urbervilles. Ed. Tom Dolin. London: Penguin, 2003.

Harmon, William. “Bash? and Proust: A Note on the Nature of Poetry.” Parnassus: Poetry in Review 11.2 (1983): 186−91.

Hopkins, Gerard Manley. The Poetical Works of Gerard Manley Hopkins. Ed. Norman H. MacKenzie. Oxford: OUP, 1992.

Housman, A. E. A Shropshire Lad. London: Kegan Paul, 1896.

Housman, A. E. A Shropshire Lad. Intr. William Stanley Braithwaite. Boston: Branden Books, 1982.

Jakobson, Roman. “Closing Statement: Linguistics and Poetics.” Style in Language. Ed. Thomas A. Sebeok. Cambridge, MA: MIT P, 1960. 350−77.

Jakobson, Roman. “Poetry of Grammar and Grammar of Poetry.” Verbal Art, Verbal Sign, Verbal Time. Ed. Krystyna Pomorska and Stephen Rudy. Minneapolis: U of Minnesota P, 1985. 37−46.

Jakobson, Roman. Six Lectures on Sound and Meaning. Trans. John Mepham. Hassocks: Harvester P, 1978.

Jakobson, Roman. Six leÇons sur le son et le sens. Paris: Editions de Minuit, 1976.

Jakobson, Roman and Linda R. Waugh. The Sound Shape of Language. New York: Mouton de Gruyter, 2002.

Jakobson, Roman, et al. Language in Literature. Cambridge, MA: Belknap P, 1987.

James, Henry. “The Middle Years.” 1893. The Author of Beltraffio, The Middle Years, Greville Fane, and Other Tales. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1937. 77−106.

Lockwood, W. B. A Panorama of Indo−European Languages. London: Hutchinson, 1972.

Lockwood, W. B. Indo−European Philology: Historical and Comparative. London: Hutchinson, 1969.

“Long Time No See.” Wikipedia: The Free Encyclopedia. 24 July 2012 <http:⁄⁄en.wikipedia.org⁄wiki⁄Long_time_no_see>.

Partridge, Eric. A Dictionary of Catch Phrases, American and British, from the Sixteenth Century to the Present Day. Rev. ed. Paul Beale. New York: Stein and Day, 1986.

Pound, Ezra. The Cantos of Ezra Pound. New York: New Directions, 1989.

Saussure, Ferdinand de, Charles Bally, and Albert Sechehaye. Course in General Linguistics. 1916. Trans. Wade Baskin. New York: McGraw−Hill, 1966.

Turner, Frederick J. The Significance of the Frontier in American History. Indianapolis: Bobbs−Merrill, 1893.

Turner, Victor. The Forest of Symbols: Aspects of Ndembu Ritual. Ithaca: Cornell UP, 1967.

Weber, Max. “Charismatic Authority.” The Theory of Social and Economic Organzation. Trans. A. M. Henderson and Talcott Parsons. New York. OUP, 1947. 358−63.

Ring out, wild bells, to the wild sky,

Ring out, wild bells, to the wild sky,